Flannery O'Connor: The Making of an American Master

Mark Bosco, S.J.

Georgetown University

Angela O'Donnell

Fordham University

DATE: Thursday, November 4, 2021

TIME: 5 - 7:30 pm

LOCATION: Devlin Hall 101

Abstract

Please join us to watch a film about one of America's most iconic Catholic writers followed by a discussion with the film's producer, Mark Bosco, S.J.,and one of the most respected scholars of O'Connor's work, Angela O'Donnell of Fordham University's Curran Center for American Catholic Studies.

Speakers Bios

Mark Bosco, S.J., Ph.D., is Vice President for Mission and Ministry at Georgetown University, and holds an appointment in the Department of English. A native of St. Louis, Missouri, Fr. Bosco joined Georgetown after fourteen years at Loyola University Chicago, where he was a tenured faculty member with a joint appointment in the Departments of Theology and English. From 2012-2017, he also served as Director of The Joan and Bill Hank Center for the Catholic Intellectual Heritage at Loyola.

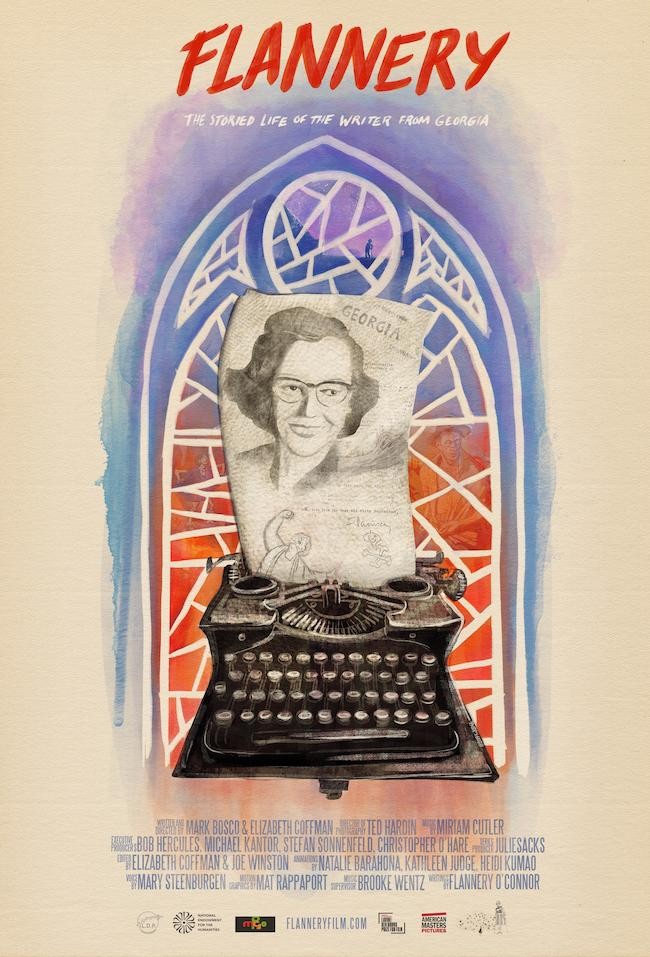

As a scholar, Fr. Bosco has focused much of his work on the intersection of theology and art—specifically, the British and American Catholic literary tradition. He has published on a number of authors, including the writers Graham Greene and Flannery O’Connor. He is also co-producer and co-director of the film Flannery, which won the 2019 Library of Congress Lavine/Ken Burns Prize for Film, and which premiered on PBS American Masters on March 23, 2021.

Angela Alaimo O’Donnell, PhD is a professor, poet, and writer at Fordham University in New York City and serves as associate director of Fordham’s Curran Center for American Catholic Studies. Her publications include two chapbooks and seven collections of poems, most recently, Andalusian Hours (2020), a collection of 101 poems that channel the voice of Flannery O’Connor, and Love in the Time of Coronavirus: A Pandemic Pilgrimage (2021). In addition, O’Donnell has published a prize-winning memoir, Mortal Blessings (2014) and a book of hours based on the practical theology of Flannery O’Connor, The Province of Joy (2012), and her biography Flannery O’Connor: Fiction Fired by Faith (2015) was awarded first prize for excellence in publishing from The Association of Catholic Publishers. Her new critical book on Flannery O’Connor, Radical Ambivalence: Race in Flannery O’Connor was published by Fordham University Press in 2020.

Read More

Bosco, Mark. “Trump’s cuts to the arts are threatening this Jesuit priest’s documentary on Flannery O’Connor.” America (March 28, 2017). https://www.americamagazine.org/arts-culture/2017/03/28/trumps-cuts-arts-are-threatening-jesuit-priests-documentary-flannery.

__________. “Flannery O’Connor: A walking contradiction on race.” America (July 27, 2020). https://www.americamagazine.org/faith/2020/07/17/flannery-oconnor-walking-contradiction-race.

Bosco, Mark and Brent Little, editors. Revelation and Convergence: Flannery O’Connor and the Catholic Intellectual Tradition. Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 2017.

Elie, Paul. “How Racist Was Flannery O’Connor?” The New Yorker (June 22, 2020). https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/06/22/how-racist-was-flannery-oconnor.

O’Donnell, Angela. Radical Ambivalence: Race in Flannery O’Connor. New York: Fordham University Press, 2020.

__________. Flannery O’Connor: Fiction Fired by Faith. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2015.

__________. “How Flannery O’Connor Found Her Art & Her God in Her Letters.” America. August 8, 2008. https://www.americamagazine.org/arts-culture/2018/08/08/how-flannery-oconnor-found-her-art-and-her-god-letters.

__________. “The ‘Canceling’ of Flannery O’Connor?” Commonweal (August 3, 2020). https://www.commonwealmagazine.org/cancelling-flannery-oconnor.

Parker, James. “The Passion of Flannery O’Connor.” The Atlantic (November 2013). https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2013/11/the-passion-of-flannery-oconnor/309532/.

In the News

Reading Flannery O'Connor Today

America Magazine includes a look back at one of America’s most iconic Catholic writers, Flannery O’Connor, in their Fall 2021 literary review, re-examining her works in a modern lens. Author Hannah E. Ryan points to the “internal dissonance” between O’Connor’s social commentary and theological vision, and the recent revelations of racism that was present throughout her life. In light of this legacy, Loyola University Maryland recently renamed Flannery O’Connor Hall, a campus residence hall, to Thea Bowman Hall.

(L to R) Mark Massa, S.J., Angela O'Donnell, Mark Bosco, S.J., and Zac Karanovich

Photo Credit: Christopher Soldt, MTS

On Thursday, November 4th, the Boisi Center hosted a film event followed by a panel discussion on the 2019 documentary “Flannery: The storied life of the writer from Georgia,” a film following the life and private insights of acclaimed American author Flannery O’Connor. Mark Bosco, S.J., director of the film and a respected scholar of O’Connor’s work, and Angela O’Donnell of Fordham University’s Curran Center for American Catholic Studies were the panelists engaging in discussion with Boisi Center’s director Mark Massa, S.J. as moderator.

The documentary began with a discussion of Flannery’s early life. She was the only child of Edward O’Connor and Regina Cline and spent most of her adolescence in a family home in Milledgeville, Georgia. Flannery’s father fostered her creativity and writing. Ed O’Connor died when Flannery was 15 from lupus. At the time, there was no treatment for the disease, and his death was a major turning point in her life.

In 1942, Flannery started at the Georgia State College for Women. She was a gifted caricaturist and her cartoons were published throughout the student yearbook. Flannery was shy but ambitious; although she was not a self-identifying feminist, she was certainly independent. In 1945, she was accepted into the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and obtained her Master of Fine Arts degree by 1947. At Iowa, she learned not just how to be a writer, but a faithful, Catholic writer. She spent a lot of time speaking to God in prayer, as reflected in her journals of the time. Flannery traveled to Saratoga Springs, New York after her time in Iowa to be a part of the Yaddo artist community. After her time at Yaddo, she briefly lived in Manhattan before moving into Robert and Sally Fitzgerald’s home in Redding, Connecticut. It is here that she published her first novel, Wise Blood.

Soon after publishing her first novel, Flannery began to experience a profound pain and lethargy in her limbs. Upon medical examination, it was determined that she did in fact have lupus, but her mother decided not to tell her as she figured the shock would be too distressing. She moved back home to Milledgeville and began cortisol therapy. She wrote in the mornings, but was often weak and tired by the afternoon. Flannery’s dark view of the bodily experience, evident in most of her novels, was most certainly connected to her struggle with lupus. She died at the age of 39.

Flannery, although beloved for her writing, had intricate and complex stances on certain aspects of public life. Being a woman from the south, she was reared in a community that was deeply racist. She, herself, would use racist language in her novels. The question of whether or not Flannery was a racist was addressed in the panel discussion. Bosco responded by saying that although Flannery engaged with racism, she was aware of the sinfulness of it. In her novels, he said, the reader can see her struggle with the idea of racism being the great sin, “but she is embedded and implicated in it.” O’Donnell responded to the question with a similar point, noting that although Flannery knew racism was a profound problem, she suffered from it. Her choice not to meet with James Baldwin in Milledgeville, for example, showed how she was an integrationist by belief, but a segregationist by choice. Flannery, when asked about this decision, said “I have to abide by the rules of the society I feed on.” O’Donnell found this quote especially interesting, as if Flannery were some parasite feeding on the stories of southerners and spitting them out for public consumption.

Bosco and O’Donnell also discussed Flannery’s support of same-sex relationships, evident in her close, accepting friendship with Betty Hester. O’Donnell noted that O’Connor had always had close relationships with her female friends, while having tumultuous and disappointing relationships with men. When Hester revealed her sexuality to Flannery in a letter, O’Connor responded by saying that she loved her and that it did not bother her in the slightest. This was especially progressive for a woman in the south at the time, but Flannery loved her friends and stayed committed to them. The panel was also asked about Flannery’s preference for the short story, and how the form specifically lent itself to her meaningful writing and storytelling. Bosco noted how the Biblical parable is similar to the short story, and that Flannery’s parable-resembling narratives worked well in that specific form. Even her novels were episodic. She had such a dramatic imagination and liked working within a constrained writing form.

Finally, Bosco was asked if he would consider making a second documentary. He explained that it took nine years to make the film, and that over the course of filming the first documentary, they developed 42 hours of material. He noted that there was so much more he would have liked to unpack in the documentary about Flannery’s struggle with racism and her commitment to Catholicism, but they had to significantly cut down the documentary to just an hour and a half. If given the opportunity, he would love to explore more of her experiences with feminism, race, disability, and Catholicism. “While making the documentary, we just fell in love with Flannery,” Bosco said. O’Donnell nodded in agreement.