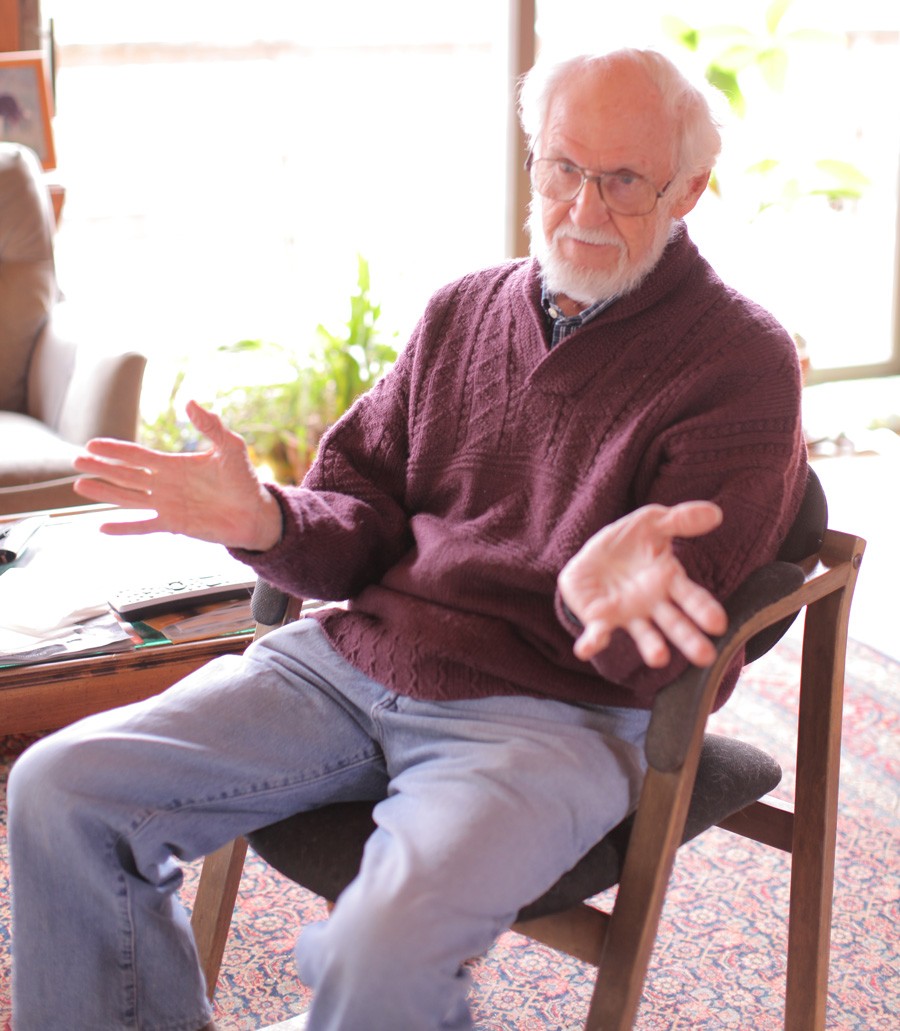

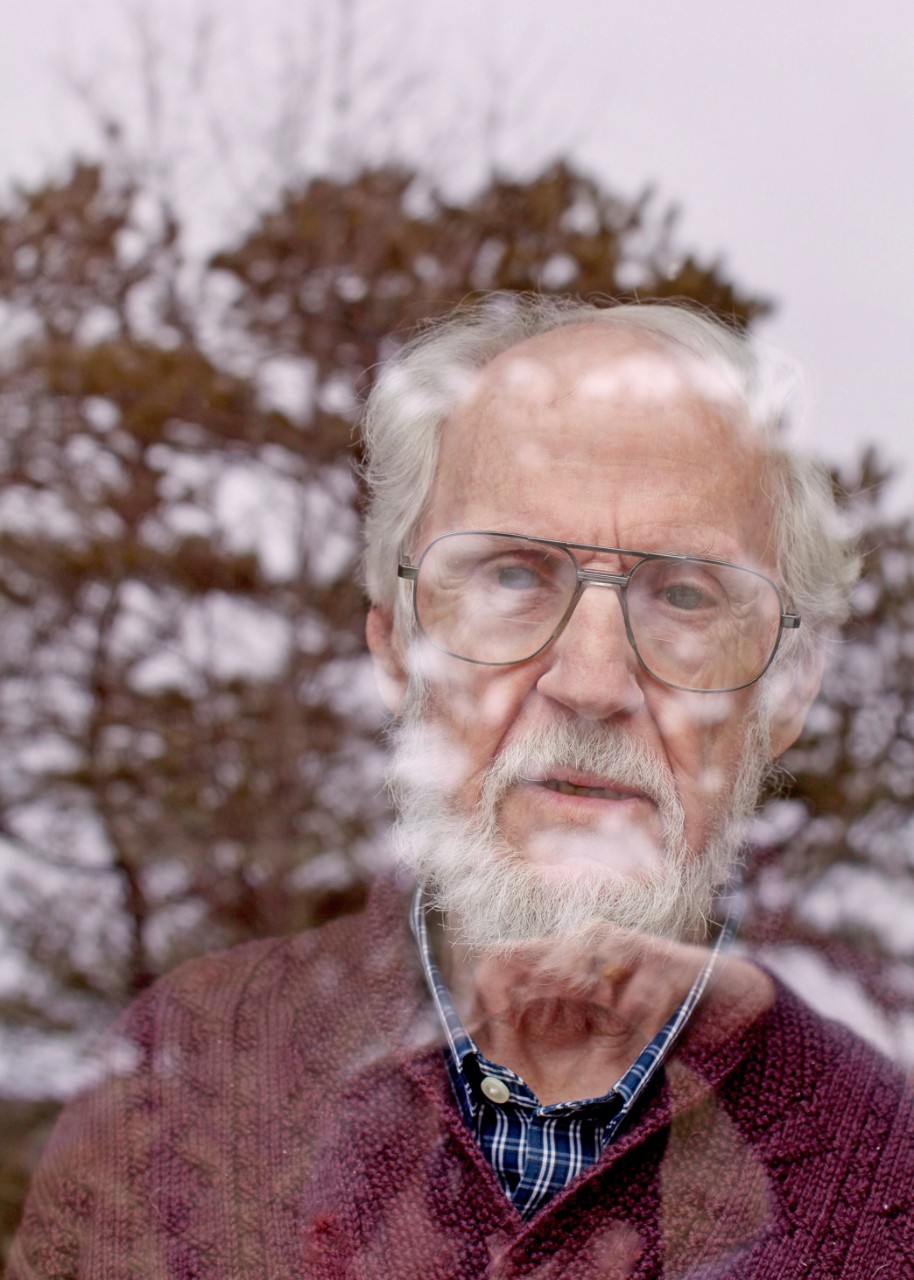

Surprising Himself

Poet Brendan Galvin ’60 graciously shared several unpublished poems with Boston College. They explore some of his most enduring passions: the sheepdogs he loves and the birds he watches avidly as they visit his porch; his beloved wife, Ellen, and the woman he loved after her death and then lost to cancer; and always the Truro landscape he has chronicled for much of his life.

Glenfillan Sheepdog Trials

Once it took the field

we forgot its ripsaw profile

and the tail barely a rope fray,

no rudder, and the whole

satchell-with-legs look of it

alongside the Sampsons

and Delilahs of the breed.

Locked in its work trance,

mind over sheep-fuddle,

streaking out low it collected

and bullied them as though

they were stray thoughts

of the shepherd who stood,

cap over brow, canny,

whistling his dog through all

the right moves: when

to charge, lie low, display

just the exact hint of threat

to back that big ewe down,

then go neat-footed, closing

the distance, adjusting

the angle, black-and-white

verb to the flock’s blackfooted

milling. How long after these canids

willingly approached our fires

did it take for some magus

to train one up to these workaday

marathons, this serious play

that involves everything from

pick-up-sticks to a log-roller’s

quickstep over the backs

of Charolais built like a herd

of tractors? Now it has queued

the flock up at the second gate,

walked them through it and home

again to that foxy whistler

who’s swapped his Wellingtons

for soft Italian loafers today.

The dog cuts two out of the flock,

melds them in again, heads them

toward the pen while a beauty

without vanity shimmers unaware

of itself over the rough field,

shivers the spine as—applause

like a smattering of stock doves

flying—the white gate closes.

A Thank-You On Lugh's Day

Ellen Baer Galvin 1935–2014

The first whip-poor-will in years

sings to adore the hour. Once

that American nightingale

deepened the colors of every

evening’s going, and I lay

in fresh pajamas and bathsoap,

letting the downstairs adult voices

talk me into the dark the way

Anne as a baby went to sleep

years ago (or was it yesterday?)

reciting Mama, Papa, naming

even Blackie and Tigger.

Four a.m. is time and voices,

distances and rooms, the surprise

that you were always here among

every thankful thing, and knew

the names of the flowers. And let’s

praise the grace or dumb luck

that shadowed us along the possible

sideroads and through the right doors

to Love, that led us to a Deerfield orchard

in bloom, and married us on the Celtic

feast of Lugh, god of the arts and harvests,

and thank the twin lights of Chanukah

and Christmas, that brought us to

46 Lughnasa mornings when we woke

to each other’s unguarded faces.

Like a Prisoner on Papillon

Another April morning snow here

on Egg Island, so I feed the woodstove

and think of you drinking coffee

across the barrier water on your

South Fork, wishing as we both do

that the ferry was direct, without

a three-state obstacle and sometimes

forbidding weather that spins off

Africa and tracks the Gulf Stream north.

Do we give storms human names and eyes

to personify the control we’ll never have,

since they are shape-shifters that could

shave our islands of all our Love

and us in an hour or less? Today I'm

stuck with memories of our first meeting

at the Mary Ellen’s off-ramp, when I said,

You’re beautiful. It was no lie, though

I’m serving time for it this morning.

Yellowthroat/Yellowrump

1. Before the Wolf Moon

Are you early or late? That’s

what my father used to ask

when I dragged home sticky

and oiled from spraying roads

with asphalt, and what I want

to ask a yellow-throated warbler

as rain on my woodpile tarps

thickens to ice.

If it snows

again tonight the cardinal’s

suit of flame won’t even warm

imagination, but I’ll rise early

tomorrow and hang a chunk of suet

for that yellow-throated one

who’s lighter and more fleeting

than my pocket change,

and too far north to be delving

into pine cones for sustenance.

Come January, the locals will be

vocalizing in tangles of underbrush

and oak scrub, and hanging, feeding

on my rewards, or scrambling their flocks

like winged ampersands against the raptors,

and this yellow-throated southerner

will amount to a single week logged into

a field manual a half-century old.

2. Winter Warbler

When the north wind blew it

like a fireworks of feathers

at the windows and past the hanging suet

and seeds, I never saw any owl

or merlin, it was over that quickly,

and I hoped the victim wasn’t

a yellow-rumped warbler

as the blown colors hinted—

blue-gray, black-and-white, a touch

of lemon. First thing the following morning

I put out the feeders I retrieve

against raccoons before each sunset,

and faster than coffee can brew

the complete bird was there,

batting cleanup for crumbs on the railing,

the only warbler that winters on this coast,

surviving on bayberries, waiting around for

weevils, borers, maggots, grubs, sawflies,

things that make holes in other things.

Voices From The River

The visibility is zilch, like cold black coffee,

so I swim around down there till I bang

my head on a fender or hood—talk about

NFL concussions—then tie a buoy

on whatever’s available,

a mirror or door handle.

*

Effortless, spontaneous as joy,

the birds send up their common cry.

Our keelboat has pushed off

the snags again and passed over

sunken timbers. We have resisted

the dark again, and cannot wait

for today. Out beyond us,

where pinetops dovetail with the horizon

a whip-poor-will sings to detain the hour.

Who knows this river’s original name?

Tribal mapmakers drew these streams

without their bends and rapids, as though

the traveler’s route was a straight line,

and the name changed with

the occupying tribe.

*

If the vehicle’s

been down there long enough, sometimes

I can put my hand right through the body

like into a bag of chips. Then

the power-hose team comes out and they

blow the gunk off, or mostly, before

the tow truck can drag the car up.

*

I, Israel Whelan, Purveyor of Public Supplies,

bought these chips of metal and glass

you might think auto parts now

at the shops of Parker and Voigt, watchmakers.

Once these fractions were a chronometer.

*

Even ashore it looks so muddy a kid

in pre-school maybe tried to make a car

out of play-dough, except you still can’t tell

if it’s a ’56 DeSoto or a Hudson Terraplane.

So many down there when they lowered

the water to repair the dam it looked like

the parking lot for an underwater Walmart.

*

The white man gives us solid water

but shining like the sun, then shows us

our faces in it. When more come,

pale as snow and slow of thought,

clothed in animal skins unknown to us,

saying they are children of the Great Father,

and plowing the bones of our fathers,

laboring without laughter, how long before

no one will dare taste this stream,

or interpret its starlight

in the weak flicker of candles?

Who then will know the way

to the home of the Winter

Corn Spirits, or if Red Alder Creek

flows from the Wallacut River?

The Singing Water they call

Bald Head Rapids, where at the arrival

of the salmon, the woman of our tribe

with power over fish conducts her ceremony.

Each boy and girl is gifted

with a piece of the first caught.

*

Insurance fraud, murder, hotwired joyrides

from twenty-two states and the province

of Quebec, according to license plates. River’s

a huge wet magnet, Hammy Snyder says,

and pries the panels and compartments

for small fish trying to make it through

winter in a car.

*

Saturnism it was called, and later

Painter’s Colic, because the wines

and pigments they favored created

gout, fatigue, delusions sometimes,

toothlessness, depression,

cadaverousness. Water above

fifteen parts per billion

and we call it lead poisoning.

Batteries, auto repair workers, gasoline,

water pipes, even roofing materials, pottery glazes,

cosmetics, and of course paint.

Even today a housepainter who begins

espousing the irrational on a regular basis

may be diagnosed with Saturnism.

*

Sometimes Hammy pours

bucketfuls of hornpouts and bluegills

back into the water. But before

the fishing Trooper Lucey has to check

front and back for bodies. If he says,

We got another Swamp-thing,

the rest of us head for the trees.

A Promise

Worm-eating warbler at first,

waiting your turn after the jays

and blackbirds at the suet,

but no worm, and a cinnamon cap

instead of headstripes. Fifty years here

and as the ice caps melt

the tides grow higher and deeper

out of the North, and from

the low-country south of swamps

and river bottoms new birds migrate.

Last August a pair of swallowtail kites,

and now a Swainson’s warbler, you,

rare even to ornithologists, hardly seen

north of the Chesapeake let alone here

in coastal Massachusetts, where maybe

six is the all-time count. Your name

translates to “Marshy Lake,”

and here you are by Heron Pond.

As for me, I’ve logged Manx shearwaters

and hoopoes, wheatears and various wagtails,

a couple of Africa-bound turnstones

on a freighter’s rail, even flown

to the chachalacas and chukars.

Hunting sustenance, you skulk and shuffle

along the ground, overturning leaves,

flipping fodder, a monotype, one of a kind.

Therefore I will not turn you in for any notice

or official count. Let the flyway

that passes my door keep our secrets.

©2020 Brendan Galvin