Originally published in Carroll Capital, the print publication of the Carroll School of Management at Boston College. Read the June 2025 issue here.

It had been a particularly gruesome day in Troy, circa 1100 b.c., as told in Homer’s Iliad, a legendary account of the Trojan War. Two valiant soldiers on opposite sides of the war—Glaucus, a Trojan ally, and Diomedes, the Greek—come face to face in the twilight of battle. They indulge in some rhetorical combat, informing each other of the irimminent demise. But they keep talking. Glaucus says that his father sent him to Troy with strict instructions: “Ever to excel, to do better than others, and to bring glory to your forebears.” The two quickly realize that their grandfathers were friends who extended warm hospitality to each other. They step down from their chariots, take each other by the hand, and vow friendship. “There are enough Trojans left for me to kill,” says Diomedes, less sentimentally.

Switch scenes to Chestnut Hill, 1914: Boston College has created a new college seal. Depicted in the center is an open book with the Greek words aien aristeuein—“Ever toExcel”—across the pages. Those words remain the motto of Boston College, a fitting description of a school that began as a commuter “streetcar” college for the sons of Irish immigrants, and journeyed toward becoming a leading national research university.

Today, “Ever to Excel” can also serve as a powerful mantra for managers and leaders everywhere. The message: Don’t get comfortable. Wake up each morning feeling constructively dissatisfied with the status quo, no matter how well things seem to be going. Look for ways to consistently “do better,” as Glaucus’s father instructed. This mindset isn’t about perfectionism; it’s about a commitment to progress—for ourselves and our organizations.

.jpg)

Illustration by Bryce Wymer

Now let’s look at the daunting reality.

What often stands in the way of continuous improvement is nothing more or less than our normal workday. At any given time, we’re consumed by routine and random tasks: checking emails, attending meeting after meeting, reacting to surprises and urgent situations, and advancing existing projects. All necessary work, to be sure. But what about the crucial habits that lead us and our organizations to get better and better, to elevate performance, to sustain excellence through innovations both big and small?

These are habits of learning in the broadest sense: hunting for meaningful ideas, reaching across unfamiliar boundaries to intentionally collide with diverse and contrasting opinions, and experimenting to assess the value of new ideas for change. Each of these practices requires an investment of time dedicated to learning that creates the future.

The problem is that we, as leaders, are often trapped by the present world around us. Leadership’s attention is more often than not prescribed by the organizations we live in, as the esteemed scholar and strategist William Ocasio described in his seminal paper, “Towards an Attention-Based View of the Firm.” Our priorities, opportunities, and challenges are lashed to the collective ecosystem of information flows, systems, routines, processes, and communication channels. All too often, we find ourselves inside an “iron cage” that prevents us from stepping beyond the day-to-day to seek fresh perspectives. I quote here the great German sociologist Max Weber, who used the cage metaphor to describe how leaders become captives of bureaucratic capitalism. Caught within rigid systems, they can easily lose their freedom and creativity, Weber explained in his 1904 classic The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism.

Weber asked, “Who will bend the bars of this cage?” My answer: Each one of us can and should, by developing “Ever to Excel” habits for leaders, which help us respond to not just immediate and well-trodden concerns but also tomorrow’s unknowable challenges. These are ways that we put the “ever” in “Ever to Excel."

Charlie Munger

Some of the busiest people have made a point of protecting their time for learning. One of my favorite examples is Charlie Munger, best known as Warren Buffett’s business partner at Berkshire Hathaway, but also a modern-day sage in his own right. Munger (who died two years ago, just before his 100th birthday) hit upon one strategy when he was a young lawyer. He would, as he put it, “sell the best hour of the day to myself.” All the incentives and pressures of his job were driving him to take on more billable time, but he shaped his own learning flow by taking that valuable (monetary) time and dedicating it to something even more valuable, his own reflection and learning. “And only after improving my mind—only after I’d used my best hour improving myself—would I sell my time to my professional clients,” he said at a shareholder’s meeting some years ago.

In a commencement speech back in 2007, Munger said of his friend and partner, “If Warren had stopped learning early on, his record would be a shadow of what it’s been.” Munger noted that Buffett’s investment skills had increased markedly in the 12 years since he turned 65, due to habits including daily reading and conversations geared to future possibilities. “I constantly see people rise in life who are not the smartest, sometimes not even the most diligent,” he told UCLA law graduates. “But they are learning machines. They go to bed every night a little wiser than when they got up.”

We do face the realities of the clock, the calendar, the schedule. As my friend and colleague Howard Weinberg (also a member of my Carroll School advisory board) has repeatedly emphasized: “Time is our scarcest resource.” How we allocate that time is an often-ignored “strategic” decision we all face. A past boss of mine, Peter Lorange, now president emeritus of IMD (International Institute for Management Development) in Lausanne, Switzerland, often reminded a much younger me: “Andy, you are all over the map. Remember, your strategy is choice.” In other words, our own personal strategy as leaders and professionals is made up of both implicit and explicit choices we make each day about how to spend our time. Is that decision too often dictated by the relentless organizational ecosystem that surrounds us (as Ocasio insightfully surmises)? Alternatively, can we much more effectively take control and manage our time, making choices that allot parts of our day to identifying and learning new ideas?

“ I constantly see people rise in life who are not the smartest, sometimes not even the most diligent. But they are learning machines. They go to bed every night a little wiser than when they got up. ”

I sometimes find myself shuffling papers, sitting in optional meetings, managing my inbox, and performing other tasks that are not absolutely necessary or don’t need to be done now. I suspect many leaders share this experience. Organizations have a way of consuming our schedule, which is precisely why we must be extraordinarily intentional and even courageous with our time, taking back that scarce resource and using it for our own and our organization’s learning. We can decline invitations, reduce email time, delegate tasks, and question “false deadlines” by asking ourselves whether something is truly urgent. We can find proactive ways to break out of the iron cage.

Part of this liberation is to go outside the organization for new insights, inspiration, and ideas—outside of our well-established teams, social networks, and our fields of specialization. Decades of research have demonstrated that project teams that remain together for extended periods without meaningful changes in their composition (bringing in people with different backgrounds and experiences) are less likely to generate innovative ideas. Why? Because members of long-running teams habitually draw ideas from a narrow band of sources: each other. They seldom communicate with people working on different projects in other departments, or at least don’t rely on them for ideas. So their ideas keep recirculating within the group, making fresh solutions harder to discover.

%20.jpg)

Seidner University Professor Paul Romer

In his studies reported widely in both academic journals and popular media, the sociologist Ronald S. Burt has found that, on the other hand, standout ideas come from managers who forge conversations with people outside their immediate circles. Those people span what Burt refers to as “structural holes,” gaps between different groups of professionals—between, say, sales and engineering staffs. And why are ideas so critical and powerful in the first place? As a daily reminder, all I have to do is walk down the hall in Fulton and by the office of Seidner University Professor Paul Romer. He won a Nobel Prize in economics for demonstrating how ideas propel innovation and growth, and he looks for ideas in all places, something we encourage every student to do.

There are ways to find new ideas that shape the future without huge investments in time. Being a careful observer of everyday life around us is a critical habit of the “Ever to Excel” leader. Countless innovations have resulted from simply following baseball legend Yogi Berra’s offbeat wisdom—“You can observe a lot just by watching.” Take frozen foods, for example.

In the early 20th century, hundreds of thousands of people journeyed far to take part in the Canadian fur trade. Many saw how inhabitants of the northerly regions stored their food in the winter—by burying meats and vegetables in the snow. But probably few of them entertained thoughts about how this custom might relate to other fields of endeavor. One who did was a young man named Clarence Birdseye, who spent four years on a fur-trading expedition. He was amazed to find that freshly caught fish and duck, frozen quickly in such a fashion, retained their taste and texture. He wondered: Why can’t we sell food in the United States that operates on the same basic principle? With such thoughts, an industry was born.

Clarence Birdseye

Birdseye developed the means of freezing foods rapidly and then sold his ideas and processes to General Foods in 1930. (He later developed inexpensive freezer displays that enabled a system of distribution.) His name—adapted for brand purposes as Birds Eye—is still seen by all who open freezer doors in supermarkets.

Good observers are equally attentive to their own experiences. Consider Natalie White ’20, who grew up playing basketball and experienced the discomfort of wearing sneakers designed typically for men’s feet, which puts women at greater risk of knee, ankle, and leg injuries. The realization crystallized when she saw an advertisement featuring WNBA players holding sneakers named after NBA players. “You can be the best in your game, but at the peak of your career, you’ll still be promoting products made for someone else,” she recalls thinking.

Most basketball sneakers marketed to women are basically smaller versions of men’s footwear, not designed for the slimmer width, narrower heel, and other features of women’s feet. As a student, White began collaborating with freelance shoe designers and tested early prototypes with members of BC’s varsity women’s basketball team. Her brand of basketball shoes, Moolah Kicks, is now sold in stores nationwide.

Twyla Tharp

Getting ideas is one thing; storing those ideas and keeping them within reach is another essential practice. While spreadsheets and digital documents work well, many creative professionals prefer tactile approaches. Renowned choreographer Twyla Tharp begins each project with a cardboard box labeled with the project name. “As the piece progresses, I fill it up with every item that went into the making of the dance,” she explains in The Creative Habit. She keeps notebooks, news clippings, books, photographs, art objects, even toys in these boxes. The materials for Movin’ Out, a dance musical set to Billy Joel’s hits, filled twelve boxes.

I once interviewed Ronald L. Sargent when he was chairman and CEO of Staples (he is now interim CEO of Kroger and serves on the Carroll School’s advisory board), and I mentioned the importance of filing away ideas rather than letting them evaporate. He responded instantly, “I don’t file it. I carry it.” Sargent then pulled out a thick file folder containing active ideas, including a clipping from The Wall Street Journal, a note written to himself while on a flight, a hard copy of a PowerPoint presentation, and other useful material. “I carry it with me. All the time,” he said. A file folder of ideas in the days of digitalization? It may sound arcane, but I think not. Whatever works quickly, easily, and effectively is the best idea-system for you.

Ideas also need testing: Even those we think are fabulous at first can turn out to be duds. For that reason, experimentation is an indispensable skill of leadership and learning, and a highly underrated one. Prototyping is one form of experimentation and can be as simple as soliciting verbal feedback from people, preferably including those outside your usual circles, or putting the idea in the form of a memo, a visualization on paper, or a sketch of a new process.

“ Getting ideas is one thing; storing those ideas and keeping them within reach is another essential practice. ”

Experimentation goes further. We run experiments on a regular basis at the Carroll School, which include piloting new courses and programs. In that way, teams of any kind not only test but also develop ideas, regardless of how promising they were to begin with, as Michael Schrage details in his book The Innovator’s Hypothesis: How Cheap Experiments Are Worth More Than Good Ideas. Leaders need both the confidence to put ideas to the test and the humility to quickly acknowledge when plans fall short.

The best organizations are built for this kind of productive experimentation, and yes, failure. One of my favorite statements by a chief executive was Jeff Bezos’s letter to Amazon shareholders in 2016, in which he stated: “I believe we are the best place in the world to fail (we have plenty of practice!), and failure and invention are inseparable twins.” Experimentation makes that a triplet. I think of the Carroll School as a place that encourages students to experiment with different ideas, approaches, and disciplines. For one thing, we require all of our students to venture into the Morrissey College of Arts and Sciences to take a substantial number of non-management courses, beyond Boston College’s core curriculum. Not all of their experiments will work out, and failure itself offers lessons equal to success (though they might be a bit more painful to endure).

Jim Collins

Engaging in the varied habits of learning takes more than good intentions. Leaders need to become architects of time, creating the processes, routines, and systems that will yield forward-looking ideas and possibilities. At the Carroll School, I have worked with my team to bake these practices into our daily, weekly, and monthly management lives. This means creating a variety of information flows, including data, reports, and conversations—all aimed at making sure our faculty’s teaching and research, our curriculum, and our student support are infused with new ideas and experiments in the spirit of “Ever to Excel.”

Jim Collins, in his book Built to Last, refers to these kinds of efforts as “Clock Building.” With a commitment to change and a bit of discomfort, leaders can build organizational “clocks”—processes, systems, routines, calendars, and culture—that alter the organization’s relationship to time. That encourages a healthy flow of attention to new ideas for learning along the path of excellence.

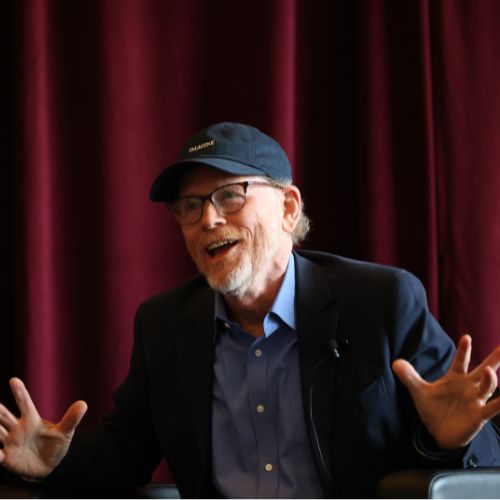

Ultimately, leadership for tomorrow requires clarity about what matters most, what we should learn about, and what doesn’t deserve our attention. Academy Award–winning director Ron Howard, who gave the keynote at our annual Finance Conference in May, says that at the end of the day, what matters to him is not how big his crews are or how much equipment he has. “What’d you get inside the [camera’s] frame? That’s all I care about,” he says, explaining that what he sees through the lens is the story he’s trying to tell.

Ron Howard

What do we, as leaders, see through our leadership frames? Every leader needs a clear perspective and focus, and everything that kind of matters or is sometimes important or that’s for show and tell can’t be inside that frame. We must identify what truly matters and maintain our strategic focus. Perhaps it’s creating exceptional customer experiences, recruiting and developing great talent, or advancing breakthrough innovations. Other aspects of our work remain important, but staying alert to our fundamental priorities is essential. What will your organization look like three, five, 10 years from now? How will you continue to develop yourself and your team to think broadly, creatively, and analytically, as we seek to do with every one of our students? Where will you find the ideas that help you to always “do better” and excel into the future?

The ancient imperative “Ever to Excel” remains as relevant today as it was on the plains of Troy. It reminds us that leadership isn’t about having arrived at excellence—it’s about the perpetual journey toward it. By breaking free from the imposed cage of the present, letting loose our time for learning, seeking diverse perspectives, observing carefully, capturing ideas, and embracing experimentation, we nurture the conditions for sustained excellence in whatever field we lead.

As you reflect on your leadership journey, ask yourself: What will you do tomorrow to bend the bars of your cage? How will you invest in the future while managing the present? The answers to these questions will help write your own story of excellence—one that continues to unfold, day after day, year after year.

.jpg)