Samantha Teixeira, an assistant professor, works with teenagers in Boston to examine how the neighborhoods in which they grow up can shape their future.

Teenagers walk up and down the streets of South Boston, stopping to take photos of the people, places, and things in the neighborhood that have helped to shape their lives.

One teenager takes a photo of the community center. Another shoots an empty bottle of alcohol abandoned on the side of a road.

“We always see those in the neighborhood,” the teen tells Samantha Teixeira, an assistant professor in the Boston College School of Social Work.

Teixeira teams up with young people to help her study how teens perceive their neighborhoods. She trains them to conduct research, provides them with iPods to capture the essence of their communities in geotagged images, and helps them organize public events to share their findings.

“We’re taught that to be objective you have to be removed from whatever you’re studying, and I reject that,” says Teixeira, who for the past five years has examined the social, political, and economic factors that have shaped the lives of young people who live in Dorchester, Roxbury, and South Boston. “I think that the experts on the things we’re trying to learn about as social workers are the people who lived those things.”

Teixeira says that children who live in neighborhoods steeped in racism and abandoned by local governments often struggle to reach their potential. “Where you grow up matters,” she says. “Increasingly, research is showing that early childhood neighborhood conditions have long term impacts.”

Her ongoing research project in South Boston focuses on teens who live in a public housing community that’s scheduled to be redeveloped to provide a mix of affordable and market-rate apartments. Teixeira teamed up with Rebekah Levine Coley, a professor in the Lynch School of Education and Human Development at Boston College, to examine how the redevelopment project is affecting teens who live in the housing community.

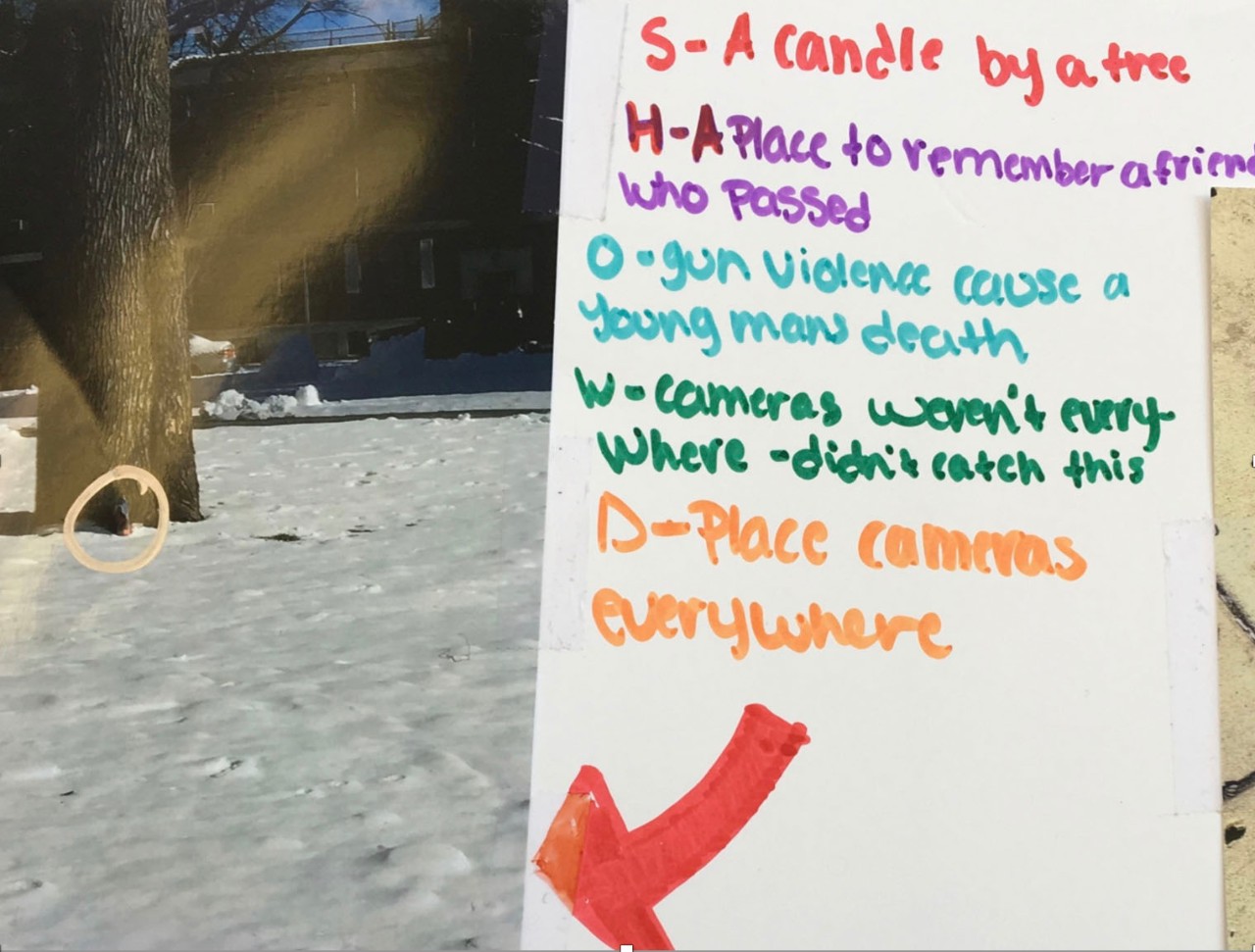

The teens took photos of their neighborhood, recorded their impressions with lapel microphones, and analyzed the qualitative data they gathered on tours of the community. They presented their findings to a city councilor and brokered a meeting with the Boston Police Department to discuss strategies to improve the relationship between police officers and youth who live in South Boston.

Teixeira says the teens articulated the need for city officials to clean up parks and basketball courts littered with needles discarded by drug users. They also described the importance of maintaining strong relationships with families in the neighborhood while their homes get redeveloped.

“I really try to help young people identify things in their neighborhoods that they love and things that are challenges for them,” says Teixeira, who has applied for funding from large foundations and federal agencies to support her research project in South Boston. “What we see in the research is that it generally results in good things for kids and good things for their neighborhoods.”

A teenager analyzed a photo taken in South Boston. Photo courtesy of Samantha Teixeira.

For another project, Teixeira worked with teens in Roxbury and the South End to create a survey to identify problems young people faced in their communities.

The teens administered the survey to people who lived in public housing developments, analyzed the data with help from graduate students enrolled in Teixeira’s “Community-Based Participatory Research” course, and then presented their findings to neighborhood residents, representative from nonprofits, and officials from the Boston Public Health Commission.

Half of the respondents reported that a close friend or family member had been killed, Teixeira says. Many teens wanted to see parents, peers, and community agencies connect to create opportunities for them to find jobs and further their education.

“When people work in neighborhoods with teenagers, they often come in with solutions and never ask young people whether they’re realistic,” says Teixeira, who collaborated on the project with the Melnea Cass Network, a nonprofit organization in Roxbury committed to ending youth poverty and violence. “But the kind of research that I do allows for much more of that conversation to happen.”

Shortly after Teixeira arrived at Boston College in 2015, she teamed up with six teenagers who live in Dorchester to study the dichotomy between the more affluent and poorer parts of the neighborhood.

The young people took photos of their neighborhood, geotagged them to pinpoint the location, and then presented their findings to community members at the Codman Square Branch of the Boston Public Library in Dorchester.

The teens, who worked at Youth Hub, a nonprofit organization in Dorchester dedicated to preparing young people to excel in the workplace, reported that being exposed to violence in low-income parts of the neighborhood caused trauma that limited their personal and professional success. But they also said that the bonds they forged with family and the rich culture that permeated their neighborhood promoted other opportunities to reach their goals.

Teixeira says that teens frequently picture researchers as stereotypical scientists who wear white lab coats and carry beakers filled with mysterious liquids. But the teens who collaborate with her, she says, often develop a broader understanding of how researchers can harness their expertise to improve the lives of people around the world.

“We have expertise in our own neighborhoods,” Teixeira says the teens tell her, “so we can be the scientists here and act on our own findings.”

The graduate students who help Teixeira design research projects credit the experience with helping them find their career paths. Teixeira says two MSW students who helped teens in South Boston explore their neighborhood have parlayed their research experiences into full-time positions at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, where they work to identify and analyze the health needs of Boston residents.

“They tell me that the skills they learned while working with communities and doing research were instrumental in them getting those positions,” says Teixeira. “It’s exciting to see students use social work skills paired with research skills to do these kinds of jobs.”