When Ariana Chao ’10, M.S. ’11, started her freshman year at the Connell School of Nursing, she had no plans to pursue research. “It sounded dry,” she says. Today, Chao is working on her doctoral dissertation at the Yale School of Nursing and describes her research in a way that might surprise her freshman self. She calls it “fun.”

Chao’s dissertation is on stress, binge eating, and metabolic abnormalities. In a single week recently, she received a National Institute of Nursing research grant; edited a research manuscript for publication and submitted another; conducted data analysis related to food cravings, food intake, and weight; and helped to organize a colloquium for her fellow doctoral students.

“I’ve fallen in love with research,” she says. “There are so many complex questions for nurses to answer.”

Chao is among a growing number of students who can credit the Connell School’s Undergraduate Research Fellows Program for transforming their passion for nursing into an interest in research. Now in its 17th year, the program gives undergraduates an opportunity to collaborate with a faculty member on a research project, giving them firsthand experience in nursing science. Fellows, working closely with their mentors, take on a range of research responsibilities, often in a hospital or lab, and are paid hourly for their efforts. Chao assisted Associate Dean for Research Barbara Wolfe for three years on a study analyzing the psychobiology of eating disorders—an experience she says “changed my life.”

Fellows and faculty define the goals of the not-for-credit program broadly, from cultivating research skills and strong mentor relationships to expanding students’ understanding of nursing roles. In particular, they say, the program makes real a concept emphasized in the classroom: that research is integral to excellent clinical care.

“The program sets the stage early that developing knowledge and generating evidence are part of a nurse’s responsibility,” says Catherine Read, associate dean of undergraduate nursing, who oversees the research effort with Wolfe. “These are the skills that students need to become leaders.”

According to Donald L. Hafner, who is vice provost for undergraduate academic affairs, the Undergraduate Research Fellows Program began in 1997, when Boston College undergraduate schools received donor and strategic plan funds to start student-faculty research fellowship programs. (Other top-ranked nursing schools offer comparable programs.)

Research studies on nursing education support such initiatives: exposing students to experiential research reduces the historical tendency of nursing undergraduates to dismiss research as boring and to overlook the research-practice connection. One paper published last year in the Journal of Nursing Education and Practice found that 67 percent of undergraduate nursing students who participated in a data collection project indicated that their understanding of research improved.

Participation in the Boston College fellows program has risen, Read said. In the last five years, the program has fluctuated from 38 students in 2010–11 to 65 students in 2012–13. Moving forward, Read and Wolfe hope to increase not only participation but also student work hours (the average now is four hours a week).

To Read’s knowledge, there have never been formal academic requirements for applicants, though in the past students with higher GPAs tended to be selected first. In her nine years administering the program, Read’s thinking on who should take part has changed, she said, and she is more inclined to accept students with lower GPAs from less academically privileged backgrounds. (“In such instances,” she added, “a student must demonstrate progress, produce above-average academic work, and be able to handle the added responsibility.”)

And if Connell School faculty members have enough projects to go around, all applicants are accepted; if not, upperclassmen receive priority.

As Wolfe puts it, “There are no GPA limits on who can make a difference.”

Currently, 27 out of 52 faculty members participate in the program. After students submit applications in June, Read matches each of them with one or two fellows. Some matches are naturals, such as Chao and Wolfe, who share an interest in eating disorders. Pairs of students and faculty find common ground based on the patient population being studied, the type of study being conducted, or on a broader health care specialty, such as interventions for chronic illness or health promotion.

Some students working on projects in later phases have been named as coauthors on published studies. Other fellows have presented at the campus-wide Undergraduate Research Symposium, the Sigma Theta Tau Alpha Chi Annual Research Day, and conferences for the Roy Adaptation Association, Eastern Nursing Research Society, New England Regional Black Nurses Association, and NANDA. When Jennifer Engel ’09 was working with Wolfe during her senior year, she won the student poster presentation award at the American Psychiatric Nurses Association annual meeting—an honor intended for a master’s-level participant. And Stephanie Van Dam ’13 assisted Professor June Andrews Horowitz, an expert in postpartum depression, in designing a game titled “Glad Baby, Sad Baby” to educate mothers about their infants’ emotional cues.

Read reports that the number of students now presenting outside of the Boston College campus “marks a real change. There wasn’t a lot of that going on 10 years ago.”

But fellows’ responsibilities and experiences vary greatly and depend on the stage of the faculty members’ research they become involved in. Not all research is quite so high profile, particularly in its early stages, she observes. Some fellows never set foot in a lab; instead, they might pull literature from the library or input data in their dorm rooms. Chao came on at the beginning of one of Wolfe’s studies and helped to recruit subjects suffering from anorexia, a hard-to-reach population. Chao posted flyers at area colleges, placed ads in newspapers, and screened potential participants; later, she entered data and assembled research files. Given the need for a large sample, her responsibilities didn’t change much over her three years in the program. She now employs techniques learned from her mentor, such as double-entering data, to increase the rigor of her own research.

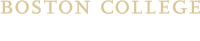

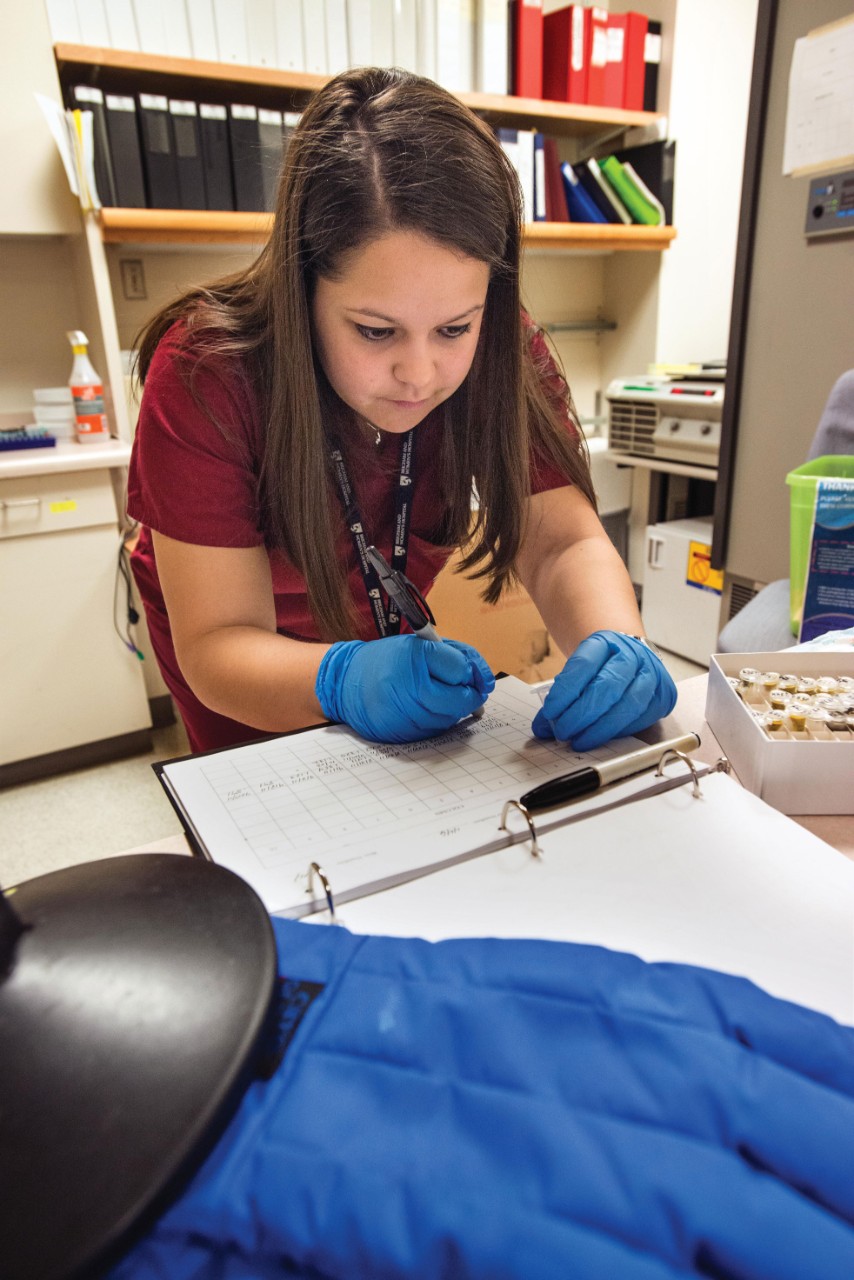

For other students, the program’s greatest reward is the access it provides to specialized medical settings. In her first year of the program as a junior, Amanda Barbosa ’14 collected stool specimens from infants in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. She was paired with Associate Professor Katherine Gregory on a study investigating how bacteria in preterm infants’ guts affect their risk for necrotizing enterocolitis. Barbosa, an aspiring pediatrics and maternal care nurse, says she couldn’t have asked for a better assignment.

“I was so excited!” she says. “I had never been in a NICU or hospital lab before.” She returned to the project this year to assist with data analysis.

Faculty mentors and students typically work together to set individual goals. But students gain from the experience, whether they are assigned to the library or the lab, undergraduates and faculty say.

One thing that all students seem to develop in the program is better critical-thinking skills. Faculty note that students they work with become better consumers of research; more able to analyze and apply scientific reading at a higher level. After logging hundreds of specimens, adding to the three years’ worth that had already been collected, Barbosa notes she not only has a better understanding of clinical papers but also greater interest in research methodologies.

Many faculty and fellows develop long-lasting mentoring relationships. A graduate of Yale’s master’s in nursing program and the Connell School’s Ph.D. program, Wolfe helped Chao prep for her admission interviews at Yale, wrote her letters of recommendation, and even drove Chao to New Haven and introduced her to one of Wolfe’s mentors, the prominent nurse scientist Margaret Grey, with whom Chao is now working. Chao says that she might never have considered a Ph.D. had it not been for the opportunity to witness Wolfe “at the head of the table,” a nurse leading an interdisciplinary team of physicians, nutritionists, psychiatrists, and other nurses in a research lab at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Wolfe and Chao have stayed in touch.

Faculty and fellows agree that the program, above all, helps students to fully grasp the critical link between research and practice. For example, Read explains, fellows shift their focus from how to do a particular task, such as start an IV or read an EKG, to why the evidence tells them that it’s the right thing to do. And Wolfe says that Connell School faculty’s emphasis on scholarship that addresses “the health issues of everyday people” further illuminates the classroom-to-lab-tobedside

connection.

“Our faculty research covers many areas of illness and mental health, but it’s all about bettering the lives of others, especially the underserved,” says Wolfe. “Fellows see firsthand how these projects make a difference by advancing and improving care.” Barbosa, who hopes to practice in a hospital and seek out research opportunities, says that she will graduate with a “deeper perspective” on the impact that nurses have on research and, conversely, the impact of research on nurses. “I now realize how much research can help us implement change,” she says. ✹

—Alicia Potter, photographs by Donna Alberico and Lee Pellegrini