Last month, the Lynch Leadership Academy (LLA) marked its 10th anniversary with a celebration and symposium at the Boston Public Library. A program of the Carroll School of Management, LLA works to provide current and aspiring principals with the professional development and one-on-one coaching needed to disrupt inequity and dramatically increase opportunities for all students. In the past year alone, LLA has worked with 263 educational leaders in 35 different communities that serve 70,000 students across Massachusetts. LLA is now extending its reach further, getting ready to launch its first out-of-state partnership, in northeastern Ohio.

Founded with a generous multi-year grant from the Lynch Foundation, the academy hosted a symposium on May 10 titled “The Intellectual and Activist Traditions in Black and Latinx Education.” Throwing light on the theme was Vanessa Siddle Walker of Emory University, who has written extensively on a hidden and often-misunderstood swath of educational history in the United States—the all-Black schools that existed in the pre-Civil Rights era, in southern school districts led by Black educators. She has recovered this history as a way of presenting one model of what American schools can be today.

What follows are some highlights of her address.

Vanessa Siddle Walker

While many Americans look to highly rated educational systems abroad for successful strategies (Finland is a favorite example), Walker argued that Black educators of the past already gave America a model for education. Referring specifically to Black educators’ pre-desegregation vision for what education should be, she said: “We have not yet begun to really import that into the present. And so it’s their vision of what education can be that I want to share.”

Each practice that these schools implemented was very purposeful, Walker said. Black educators developed “a vision that intentionally challenges the messages of the world around them, where their practices intentionally reinforce each other. And it’s implemented by staff that already believes in the possibilities of the children and owns the responsibility to help them.”

This is not the history that Walker—who is the Samuel Candler Dobbs Professor of Educational Studies at Emory—learned in her graduate studies at Harvard University. “I completed graduate school around the corner [from the BPL] and … I learned what everybody else learned: Black schools were poor schools, they didn’t have books, they didn’t have resources, the teachers weren’t good. Really, nothing good happened for Black children until we were rescued and desegregated, and then good things started to happen. That was the model that I was introduced to.”

This history was not recognizable to many Black people of past generations whom she encountered in her role as a speaker and lecturer—people who had experienced a robust education in segregated Black schools. “What compelled me—everywhere I’d go and lecture, literally across the country, if there were Black people of a certain age in the audience, they’d say ‘I went to a school just like that.’”

Walker, who has spent 30 years figuring out what Black educators at southern schools were up to, raised the “So what?” question about this history, answering that it can help us think about problems and questions we have today. Those schools of the past are gone—and Black educators were often fired in the transition from segregated schools. But she pointed out, “There’s an uncanny similarity going on here in terms of the pedagogical practices that we see with these African-American teachers and principals that we fired, and the school system in Finland that we’re trying to figure out how to imitate.”

She said, “Maybe we don’t have to look to Finland, maybe we can actually look to history to get some of these answers. That does not mean I’m suggesting we return to segregation. It does mean that we could look to the vision that [Black educators] had for what desegregated education should be.”

Walker outlined four tenets of Black educators of that era in the South and the practices they cultivated within and between their schools and communities: school climate, purposeful curriculum, professional engagement, and parental support. Throughout the contextualization and explanation of each of these features, she emphasized two things: first, that Black educators were up against both widespread racism and individual risks to their safety; and that these strategies can still be used to address issues we have in education today.

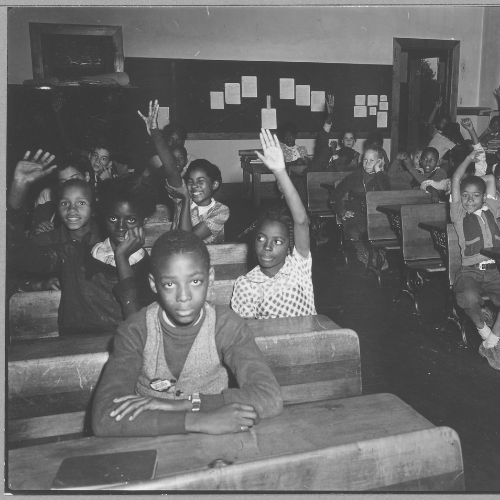

Upper-grade students in a one-room school in Waldorf, Maryland prior to desegregation (1941). Photo by Irving Rusinow, National Archives at College Park, via Wikimedia Commons

School climate: Black educators needed to counter the message that Black children were “less than,” and they did so in part with “the notion of a school climate where you can aspire to achieve, to be anything you want to be—which in real time [pre-Civil Rights] they really could not be anything they wanted to be.” Along that line, Walker spoke of the “interpersonal care” that permeated the schools, especially as reflected in the relationship between teachers and each individual student. And then there were the “institutional messages,” transmitted through assemblies, school clubs, and in others settings where educators drove home ideas about what students were able to achieve, educationally and in life. Speaking of both the interpersonal and the institutional aspects of this approach, Walker emphasized, “They reinforced one another.”

Purposeful curriculum: At a time when many school textbooks painted enslavers as good people and enslaved people as happy in their enslavement, Black educators such as Lucy Craft Laney, in 1919, called for history lessons to more accurately reflect historical events and dynamics than the textbooks at the time. Children needed (and still need) to believe they are more than how they are represented in the books; Black educators responded by teaching these students about voting and other aspects of Black U.S. history, which became a sort of “weaponized civics” that inspired them to seek change in society. “There is a curricular foundation for the Civil Rights Movement,” Walker noted.

Professional engagement: Black educators created their own associations and publications locally and regionally, connecting with each other to seek ideas and put them into practice. The educators were very “intentional” in the way they went about solving problems, and as part of one key strategy, the more experienced principals and educators made a point of constantly passing on their knowledge and best practices to younger ones. Ironically, with integration, “They had to give up the networks as they knew them.”

Parental support: Parents had their own networks, and they worked closely with teachers—who, for example, would make home visits, and in some cases even created forms of adult education for the parents. “What we have is a symbiotic reciprocity, where the parents parent the school and the teachers parent the children, and the school reaches out and supports the community. They’re all working together, as [the late author and sociology of education professor] Russell Irvine taught me. The question is, do we bother to do this today?”

In a final call to action, Walker added: “So the question is: if these people, in times where you literally could be lynched, literally, for teaching the wrong thing … could figure out how to get around some things and deliver a quality education, can’t we figure that out, too? It seems to me we ought to be able to figure out how to do that. We ought to be able to inspire our imagination and reclaim an educational heritage that is ours—all of ours—to own.”