When we were leaving the hospital after our twins died, my husband, Franco, pulled up to the entrance to help me ease into the car from the wheelchair. Then he went back inside to get something we’d left behind.

While he was gone, a car pulled up from around the back of the hospital entrance, a driveway I’d never seen before. The driver tried to turn into the circle entrance, but without realizing it, Franco had parked with our front tires blocking the exit.

So she blared the horn and glared at me.

I looked up from where I was weeping. It took me several seconds to figure out what was going on: a road I’d never seen, an angry driver, our car blocking her way (surely a sign that all was not right with my meticulous parker of a spouse).

I didn’t know what to do. I couldn’t drive because I’d just had a C-section. I tried to apologize with exaggerated expressions and explain with hand signals that the driver was coming back and we’d leave as soon as we could.

I rolled down the window in the freezing February wind to call to her, but she shook her head, clenched the steering wheel, and glared at me. Snarled, actually—teeth bared, eyes narrowed, furious hand smacking the car horn again and again and again.

I buried my face in my hands and wept as she raged. My babies’ bodies were in the morgue. We were leaving the hospital empty-handed. And here was the cruelty of the unfeeling world, blaring its blind fury at me.

Only years later could I come to see that horrible scene from another vantage point.

When we make ourselves the protagonist of every story, we forget that everyone else is doing the same.

She, too, was leaving the hospital. Pain or grief or anger could have been her story, much the same as mine. She might have been stuck there after her own worst day, in disbelief that the universe would pin her into this horrible place by a stranger’s careless parking.

When we make ourselves the protagonist of every story, we forget that everyone else is doing the same.

That awful day I wept the whole way home—wept for my children, wept for my wounded self, wept for the world that would never understand my grief. But in my pain I was unable to understand another too.

We were both stuck.

Believe me, part of me still wants to yell at that woman. I can be a lousy pacifist of a Christian, despite my daily scrappy climb toward love. But when I see her hell-bent face in my memory now, I start to turn to curiosity, which is the soft soil of compassion.

What if she and I had been able to speak? Could we have seen we were both in an impossible place? Was her story closer to mine than I realized? Might our hard edges have melted enough to let each other pass unharmed?

Right now I sense our collective rage on the roads, our toxic mix of grief and pain, our fury at being misunderstood by the other side. Sometimes we are the raging driver in the car; sometimes we are the weeping passenger in pain.

It takes a heap of humility and hope and hard work to remember everyone is only human.

But forgiveness—even years later, even to a stranger I’ll never see again—has brought freedom. I only know a handful of ways to help make a gentler world, and curiosity and compassion and kindness are among the first steps.

Whom else might I need to forgive? What freedom could come from release?

Where in your life might you need to do the same?

Laura Kelly Fanucci is an author, speaker, retreat leader, and founder of Mothering Spirit, an online gathering place on parenting and spirituality.

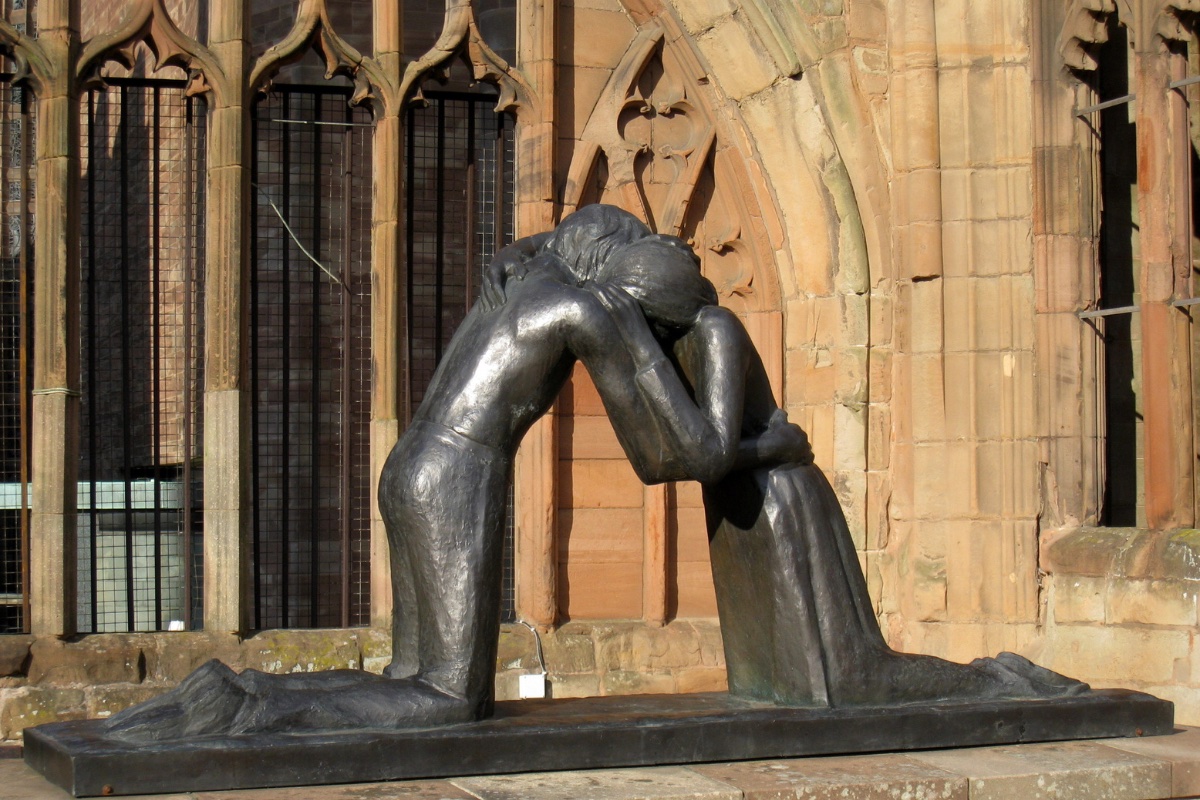

Photo credit: Tomas Ryant

The Power of Love

In an Agape Latte (a faith storytelling series) event at Boston College, theology professor Fr. Michael Himes (1947–2022) spoke to students about the power of love and family. The following is an excerpt from his talk:

Well, I've always said to my brother Ken (a Franciscan friar) that Mother was the best theologian in the family, that the two of us were just amateurs compared to her, because she got it exactly right. You may forget everything else, everything else in your life may disappear. You may forget even who loved you and how they loved you. But you never totally forget having loved someone else. You may forget being loved, but you never forget loving, because it is the most central, the most important, the most fundamental of all activities, not being loved, but loving. That’s what family gives us an intimate chance to do, in circumstances that may be very supportive or very painful, that we have the opportunity to give ourselves, to learn how to give ourselves to one another wisely and courageously and with tremendous forgiveness and deep acceptance. If you learn that, you’ve learned everything that you need to know. If you learn everything else and you never find that out, you’ve missed what it is to be a human being, because human beings are called to be the people who do what God is. God is agape, and we get to enact it. That is the most extraordinary statement about being a human being that I know.

Originally published in Catholic Families: Carrying Faith Forward, the spring 2015 issue of C21 Resources magazine.