“Reconciliation” generally refers to the rebuilding of a relationship, community, or society that has been significantly damaged by wrongdoing. People subjected to unjust treatment usually find themselves feeling resentful toward their wrongdoers. Resentment is a kind of internal moral protest that says: “I don’t deserve to be treated this way and I’m holding it against you.” Resentment is often accompanied by a desire to retaliate, especially when doing so does not come at a great cost. A resentful victim might say to herself: “I don’t deserve this kind of treatment and I’m not going to let him get away with it.” Retaliation, like resentment, can be a way of affirming one’s own worth.

Resentment can be morally legitimate. Sometimes, though, victims can feel resentment either too strongly (say, treating a minor offense as if it were major) or not strongly enough (say, not resenting a peer’s habit of making insulting comments). Retaliation for demeaning treatment can be disproportionate either by imposing too heavy a cost on the wrongdoer or by not imposing enough of a cost on the wrongdoer. Resentment and retaliation can both become destructive. Resentment can lead to bitterness and hardness of heart; retaliation can fuel ongoing cycles of mutual harm. This caution noted, sometimes injured parties have a right to feel resentment and to impose a cost on their wrongdoers.

Forgiveness is most often described as giving up both resentment and the desire to retaliate. Human experience suggests that, other things being equal, the more profound the hurt, the harder it is to forgive; in the latter case, it is usually a process rather than a single decision.

A decisive issue here for most injured parties is whether the offender has repented for his or her wrongdoing. Repenting is a process that has five components: acknowledging the wrongdoing to oneself, feeling remorse, apologizing to the victim, trying to make amends, and undertaking a commitment not to repeat the same wrongdoing in the future. The more thoroughly these criteria are met, the stronger the repentance. Victims usually find it less difficult to forgive offenders who repudiate what they have done to them; conversely, they find it harder to forgive offenders who stubbornly insist on their innocence.

If it is right to say that injured parties can, under some circumstances, legitimately resent and want to penalize their offenders, then must they always forgive? In answering this question, it helps to distinguish appropriate from inappropriate forgiveness. Forgiveness can be inappropriate when the injured party forgives in a way that suggests she does not take herself seriously. We can also point to cases at the other end of the moral spectrum. Supererogatory forgiveness is a decision to do what goes above and beyond what is morally required.

In addition to these two categories—questionable forgiving and heroic forgiving, respectively—might injured parties on some occasions have a moral obligation to forgive? I believe Christian ethics, somewhat like the tradition of Judaism, is best understood as requiring injured parties to forgive their truly and thoroughly repentant wrongdoers. It is best to think of this obligation as done from the love of God rather than because the repentant offender has a right to be forgiven. Rather than an exceptionless norm, however, we do best to think of forgiving repentant wrongdoers as a prima facie obligation—one that can be overridden in certain exceptional cases.

Forgiveness only leads to reconciliation when offended parties can renew their trust in their offenders...

This threefold categorization—forgiving that is wrong, praiseworthy, or mandatory, respectively—contradicts the widespread impression that Christians are always required to forgive everyone, regardless of the severity of the harm done or the attitude of the wrongdoer. Jesus himself teaches his disciples: “If your brother or sister sins against you, rebuke them; and if they repent, forgive them. Even if they sin against you seven times in a day and seven times come back to you saying ‘I repent,’ you must forgive them” (Luke 17:3-4; emphasis added).

This sequence is clear: if you are wronged against, confront the offender; if the offender accepts the correction and takes responsibility for it, then you must always (“seven times a day”) forgive. The conditional obligation captured in this “if” sets this norm apart from two extremes: one views injured parties who withhold forgiveness from repentant wrongdoers as always morally blameworthy; the other asserts that injured parties are never required to forgive even their most profoundly repentant offenders. The first alternative is too demanding and the second not demanding enough.

This leads to the question of how forgiveness is related to reconciliation, the restoration of a right relationship (or, by extension, the building of a just relationship for the first time). Forgiveness in the Bible usually facilitates reconciliation between injured parties and their offenders. The general biblical pattern moves from Israel’s breach of the covenantal relationship to its repair: Israel sins, God then holds Israel accountable, Israel eventually comes to its senses so that God can forgive Israel and restore their relationship. Biblical stories are more complicated but the general paradigm is communicated by Jesus when he invites sinners to accept God’s forgiveness so that they can be restored to the people of God.

The Christian paradigm envisions forgiveness as a gift given by injured parties to their offenders. Forgiveness paradigmatically culminates in reconciliation, but some acts of forgiveness are non-paradigmatic in that they do not give rise to reconciliation. Forgiveness only leads to reconciliation when offended parties can renew their trust in their offenders—this is a key reason why the offender’s repentance is decisive. The risen Jesus both forgives Peter for publicly denying him and welcomes him back into their community (“Peace be with you!”). Jesus somehow continued to trust this quite unreliable follower. Not only that, Jesus here gives him a special authority: “Receive the Holy Spirit. If you forgive anyone’s sins, their sins are forgiven; if you do not forgive them, they are not forgiven” (John 20:21, 22). Yet when Jesus prays from the cross: “Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing” (Luke 23:34), reconciliation was not possible because they were nowhere close to repenting.

The beauty of forgiveness is revealed most fully in reconciliation, but a different kind of moral nobility is revealed by victims who unilaterally forgive unrepentant wrongdoers whose own self-justifying attitude renders them (at least for the time being) unqualified for reconciliation.

Interpersonal reconciliation is always based on the giving and receiving of forgiveness between family members, friends, colleagues, and the like. But the same is not necessarily true of larger scale political and social forms of post-conflict reconciliation. As chair of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Archbishop Tutu liked to highlight ways in which forgiving perpetrators can liberate victims from overbearing resentment and bitterness. His critics, however, insisted that sometimes survivors affirm their own dignity by withholding forgiveness, especially when their offenders refuse to admit their guilt and apologize.

Reconciliation on all levels aims at overcoming enmity, establishing some degree of trust, and healing wounds caused by unjust actions and policies. Yet it functions differently after prolonged, large-scale conflict. It is a mistake, for example, to envision the process of national reconciliation as just like overcoming interpersonal estrangement.

Stephen J. Pope is professor of theological ethics at Boston College.

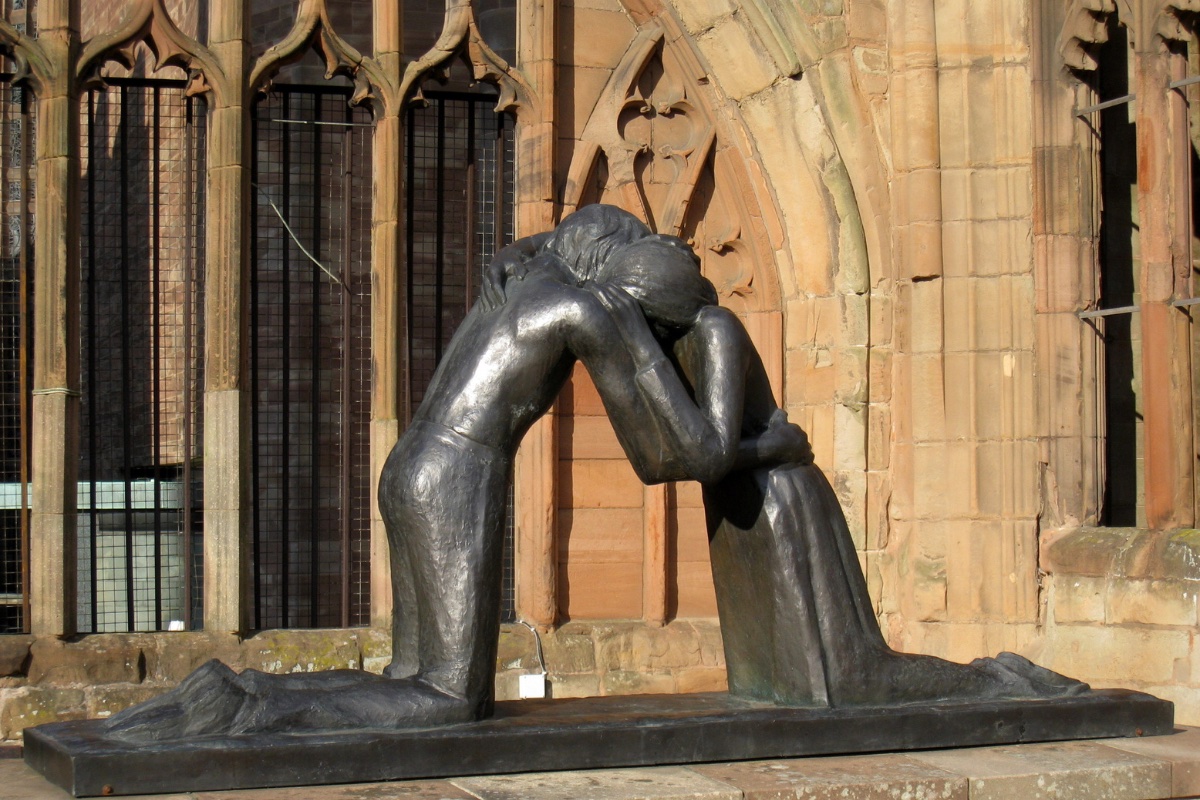

Photo credit: iStock/nm737. This tympanum by Lewis Simek adorns the main entrance to the Church of St. Peter in Porici (Prague) and symbolizes Christ's words to Peter: “I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven; whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven” (Matthew 16:19).