As I sit on my mother’s couch, I feel my teenage rebellion rise up inside me—despite the fact that I’m closer to the stereotypical age for a midlife crisis than the age at which I passed my driver’s test. The complexity of our life together, and our various roles in its many stages, is further muddied by long-term mental health obstacles. The all-too-common mother-daughter conflict is surrounded by immense pain, seemingly uncontrollable suffering, and what each person has done to survive these throes.

Mental health struggles are the most common long-term health problem on Earth,1 and more than one in five US adults struggles with mental illness every day.2 While these challenges range from manageable to severe, it is likely that you or someone in your family falls into this broad category. Understanding the prevalence of mental health obstacles is a necessary piece of the puzzle when we think about reconciliation—particularly in our families.

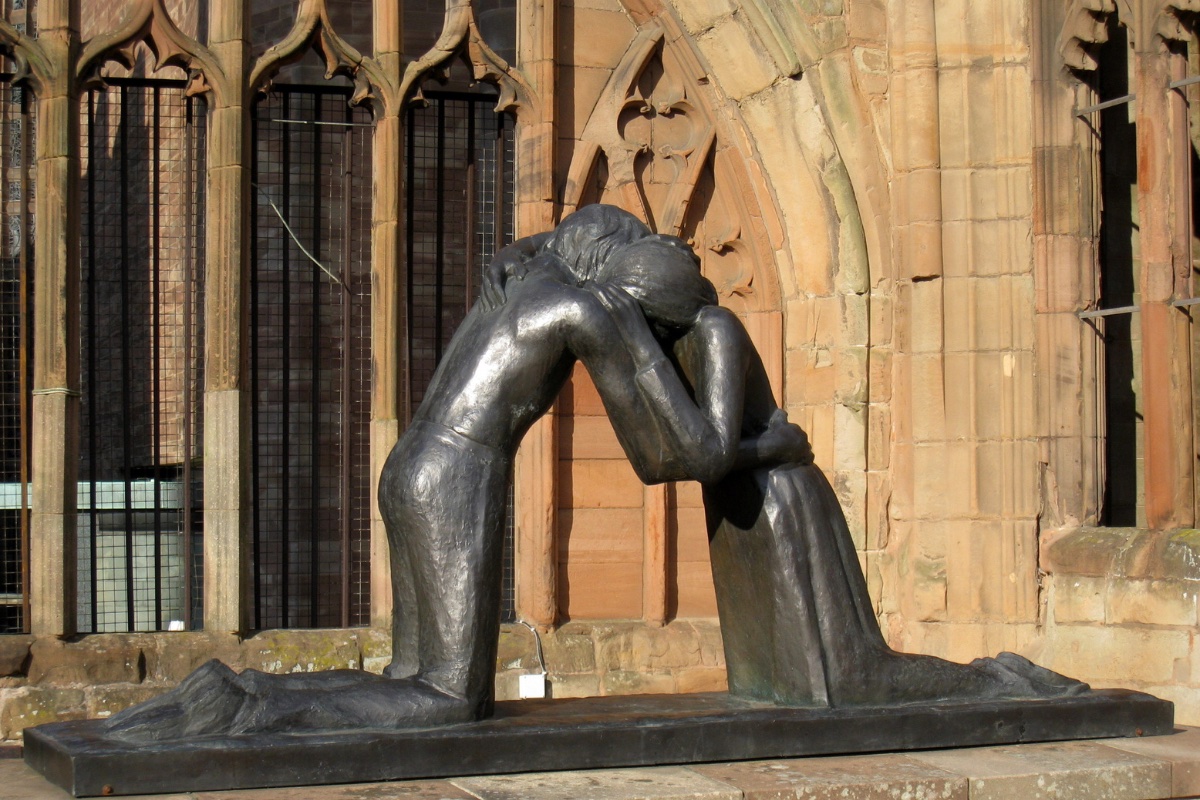

Reconciliation, in its most basic form, asks us to “restore right relationship”—first with God, and with those with whom we are in conflict. Despite its beatific intent, and the virtues fostered in the practice, enacting real reconciliation is a difficult, humbling, uncomfortable process. When mental illness is present, pursuing this good can feel impractical and fruitless. When these mental challenges are further intertwined with our families, even knowing where to begin reconciliation can feel impossible.

Here, key principles from mental health best practices can offer necessary assistance to our faith-based call to reconciliation: readiness, decentering, boundaries, and self-awareness.3

READINESS—What steps can I take to honestly assess my situation for reconciliation?

The first principle when considering reconciliation is readiness. Healing is complex, even when all our other circumstances are ideal. While you may feel called to reconciliation, another family member may not be ready, or may not be in a state of health that allows for full engagement. It is all too easy to replicate old patterns with our closest relatives, and we must recognize that there are real limits to how prepared we are to engage in a practice that asks us to transform ourselves and our relationships.

As frustrating as it may be, being realistic about readiness, and allowing ourselves to slow down a process we may yearn for, is essential. Authentic reconciliation is as much about the past as it is about forward-looking discussions that imagine, and begin to create, a healed future. If someone is not ready for this change, and/or is not open to asking for the support of qualified caring professionals (therapists, doctors, religious leaders, mediators) in the process, the time may not be right for reconciliation.

Further, the outcome of reconciliation is not guaranteed. We must ask ourselves: What resources do all family members have if reconciliation “fails,” or fails to satisfy? Will everyone remain safe and cared for during and after reconciliation? Even if reconciliation is desired by all parties, what will we do if patterns of harm are not changed? As theologian John Swinton reminds us, God’s time is slow, and rather than rush toward resolution, we often have to find patience and grace in the process of readying for reconciliation—preparing our hearts for healing that may only come in God’s time.4

DECENTERING—Am I really ready to listen, as well as speak?

Decentering is the practice of intentionally foregrounding the experience of “the other” rather than yourself. In family reconciliation that includes mental challenges, it also means recognizing that, most often, we are not the cause nor the cure for mental health. We are not each other’s savior, even while we are (or can be) each other’s comfort, resource, and loving home. While our families may be the original location of harm (I refer back to readiness if this is the case), decentering my interpretation of events or a relationship to deeply listen to another is central to reconciliation.

When involving mental challenges, our decentering capacity must grow even larger. Can I listen without judgment or anger to stories that, while true to the speaker, may have no ground in fact? Am I able to hear another’s pain and longing, no matter the form in which they tell it?5 The practice of “deep listening,” where each party is allowed to speak for a certain amount of time and the listener is not allowed to comment or question the speaker, is a powerful tool for practicing our ability to enter reconciliation with truly open hearts.6

Authentic reconciliation is as much about the past as it is about forward-looking discussions that imagine, and begin to create, a healed future.

BOUNDARIES—Am I able to name my limits in reconciliation?

Decentering is balanced with the practice of healthy, strong boundaries. Here, we must be able to name and accept the impact of words and actions, at times over the intent behind them—both mine and those of others. In reconciliation that includes mental challenges, holding boundaries means we must be able to identify ways of acting and speaking that are tied to mental health, and how these behaviors nonetheless impact the boundaries that protect our emotions, sense of self, and even our safety.

It is often very easy to let family members exceed behavioral limits we place on others with whom we interact. Your ability to calmly name and then enforce your boundaries within reconciliation is a strength that provides clarity and healthy limits to the process. The same goes for when you need to hear and respect another’s boundaries. Such limits are not reflective of a lack of love, grace, or mercy. In fact, your capacity to do the work to clarify your own, and another’s, boundaries is an expression of the care, commitment, and honesty you bring to reconciliation.

SELF-AWARENESS—Do I know myself well enough to enter reconciliation?

Despite its powerful action in our lives, reconciliation is difficult and messy. Often such efforts harm individuals while they simultaneously heal the social or family unit.7 As such, awareness of our “buttons” (the ones our families know how to push!), our ever-changing capacity for difficult conversations, and our emotional and physical needs is essential. This self-awareness leads directly to voicing and following through on actions that correspond to what we need to be our best, most loving selves. Becoming aware of yourself and the care you need is some of the best work you can do to prepare for and participate in reconciliation.

Ultimately, reconciliation cannot be forced, and family ties cannot be the final arbiter of staying in a harmful environment or relationship. Similarly, mental challenges cannot be used to excuse or continue harmful behaviors. In this complexity, hope persists. Our faith testifies to a God that exceeds understanding, and whose power of redemption is infinite. Through following these basic guidelines for reconciliation, we may be able to safely open ourselves to transformation we never thought possible.

Stephanie C. Edwards is the director of the Boston Theological Interreligious Consortium as well as adjunct professor of theology at Boston College.

Photo Credit: Adobe Stock/Krakenimages.com

Sources:

- 1 in 8 people in the world live with a mental disorder, see: World Health Organization, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-disorders

- 59.3 million in 2022; 23.1% of the U.S. adult population; this also spiked during the COVID-19 pandemic, and resulting anxiety and depressive disorders have shown long-lasting impacts, see: National Institute of Mental Health, https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness

- These are informed by the brief reflection by NAMI specialist Dawn Brown, “A mother’s message of reconciliation and restoration,” https://www.nami.org/support-group/a-mothers-message-of-reconciliation-and-restoration/, as well as the practice guidelines and ethics standards of the American Psychological Association and National Association of Social Workers. I also very intentionally treat forgiveness and reconciliation as two different, albeit related, topics. Forgiveness is a gift, as Maya Angelou says, that we can give ourselves, and is a deeply personal journey. Reconciliation, to me, is much more practical, and involves explicit actions with others that work to repair our lived relationship.

- “God's time is slow, patient, and kind and welcomes friendship; it is a way of being in the fullness of time that is not determined by productivity, success, or linear movements toward personal goals. It is a way of love, a way of the heart,” John Swinton, Becoming Friends of Time: Disability, Timefullness, and Gentle Discipleship.

- Trauma, one of the most common mental health challenges people experience, can develop into disorders such as PTSD which can make it nearly impossible for a person to tell their story in chronological order, or without embellishment from other life events or media.

- J. Chaitin, ” Transforming the Way We Speak, Transforming the Way We Listen: Dialogue and the Transformation of Relationships,” in: Standish, K., Devere, H., Suazo, A., Rafferty, R. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Positive Peace (Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, 2022), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-0969-5_56

- Jacobus Cilliers, “Reconciliation Programs Worsen Psychological Health, Study Shows,” Georgetown University Blog, May 12,2016, https://www.georgetown.edu/news/reconciliation-programs-worsen-psychological-health-study-shows/