Most Catholics are probably unaware that what we today call the Sacrament of Reconciliation existed in a completely different form during the early Christian era. Even those who are aware of this fact may not know that it was a group of Irish monks who were largely responsible for transforming this sacrament into the version with which we’re familiar. It is all too easy to imagine that the seven sacraments have existed in something like their present form from the moment they were instituted. In truth, all of them have changed in important ways over the course of the Church’s history, and none has changed more than the Sacrament of Penance.

For the Church’s first seven centuries, penance could be received no more than once in a lifetime. That policy dated back to the time of St. Peter. The New Testament tells us that Jesus gave the power of forgiveness to his disciples, but it says almost nothing about how they were to exercise it. In the early Church, the prevailing belief was that baptism was the celebration of the forgiveness of sin, and that the baptized, having turned away from sin, would not need to be forgiven again.

Nevertheless, the Church Fathers soon realized that they needed a way to deal with post-baptismal sin because many baptized Christians were slipping back into their old way of life. A formal system of public penance was devised to handle such setbacks. Typically, after penitents confessed to the local bishop, they were assigned an onerous penance that lasted several years. During this time, they wore sackcloth and garments that scratched or tore the skin as a modest reminder of Christ’s scourging. They were also required to leave Mass immediately after the homily and forbidden to receive the Eucharist. At least part of their penance consisted of long hours of prayer and fasting. Not until they had completed this long and arduous penitential period were they “reconciled” with the Church and welcomed back into full communion.

By the seventh century, it had become obvious to many that the Church’s rules for penance were not working as they were intended to, but there were still no plans in Rome to reform them. It was precisely at this time that Irish monks began to travel to the European continent to proselytize the heathen Franco-German tribes. At least a century earlier, these monks had developed a different practice of penance within their own communities, adapting a little-known tradition traceable to the first monastic communities in the Egyptian desert. Like the monks in Ireland after them, they were struggling to overcome venial “faults” in their quest for saintliness, not seeking reconciliation after committing grave offenses such as murder, adultery, and apostasy. The Irish monks refined the work of Cassian, developing a system of confession in which the private recitation of sins was followed by the private performance of penance. Crucially, they not only adopted this practice themselves, but introduced it to the faithful outside the monastery, making it applicable to all sins and available to all sinners.

As the Catechism of the Catholic Church summarizes it: “During the seventh century, Irish missionaries, inspired by the Eastern monastic tradition, took to continental Europe the ‘private’ practice of penance, which does not require public and prolonged completion of penitential works before reconciliation with the Church. From that time on, the sacrament has been performed in secret between penitent and priest.” This was a radical change in the history of the sacrament. Gradually, confession went from being public to private, and from a once-in-a-lifetime rite to an as-often-as-needed practice. The “order of penitents,” segregated from the rest of the community, disappeared.

Those who associate Irish Catholicism with fire and brimstone may be surprised to learn that it was Irish monks who made penance more private and less exacting.

Although the Irish monks practiced frequent confession of their “faults”—and recommended that fellow Catholics do the same—they also continued for some time to impose severe penances on those who committed serious sins. As Hugh Connolly notes in The Irish Penitentials, the monk-missionaries brought handbooks known as “penitentials” with them on their travels. The handbooks suggested a suitable “tariff” or penance to “pay” according to the rank of the sinner, the rank of the person offended against, and the objective seriousness of the sin. Abuses were not unknown: wealthy penitents were sometimes able to negotiate a reduction in the tariff—or hire a substitute or “assistant” to carry out part or all of a severe penance. But over time, the penitentials fostered consensus about the comparative seriousness of various sins and thus made assessments of the appropriate penance more uniform and less arbitrary.

As the Irish monks made converts and founded new communities on the continent, they promoted a conception of penance aimed at restoring the sinner to a full relationship with God rather than reconciliation with the community. They also shifted the focus from performing penances to making sincere and sorrowful confessions. In this new conception, the anamchara became a soul “doctor,” empowered by God to help rescue the sinner from grave sickness of the soul, with confession serving as a kind of spiritual emetic. As one penitential handbook put it: “As the wounds of the body are shown to a physician, so too the sores of the soul must be exposed. As he who takes poison is saved by a vomit, so, too, the soul is healed by confession and declaration of his sins with sorrow.”

As P. Biller and A. J. Minnis explain in Handling Sin: Confession in the Middle Ages, it was this milder form of penance promoted by the Irish missionaries that had gained wide acceptance throughout the Christian world by the early Middle Ages. In 1215, the Fourth Lateran Council established that penance would involve private confession and that all Christians in the Latin Church would be obligated to confess their sins at least once a year. It was also at this time that penance officially became a sacrament. (The “dark box”—the confessional booth located in the rear of most churches—wasn’t invented until the sixteenth century, during the Counter-Reformation.)

Those who associate Irish Catholicism with fire and brimstone may be surprised to learn that it was Irish monks who made penance more private and less exacting. In fact, as Lawrence Mick stresses in Understanding the Sacraments: Penance, it was the bishops and clergy on the continent who regarded the penitential practices of the Irish as a dangerous departure from tradition that would make reconciliation too easy. After centuries of debate, however, Rome finally sided with the Irish. Reconciliation, the Church decided, was not to be a one-time offer. A sacrament that claimed to offer God’s mercy should not also try to ration it.

John Rodden has taught at the University of Virginia and the University of Texas at Austin. He is the author of numerous books and articles about British intellectuals.

This is an excerpt from an article that was originally published February 14, 2022. Reprinted with permission. Copyright Commonweal Magazine. commonwealmagazine.org

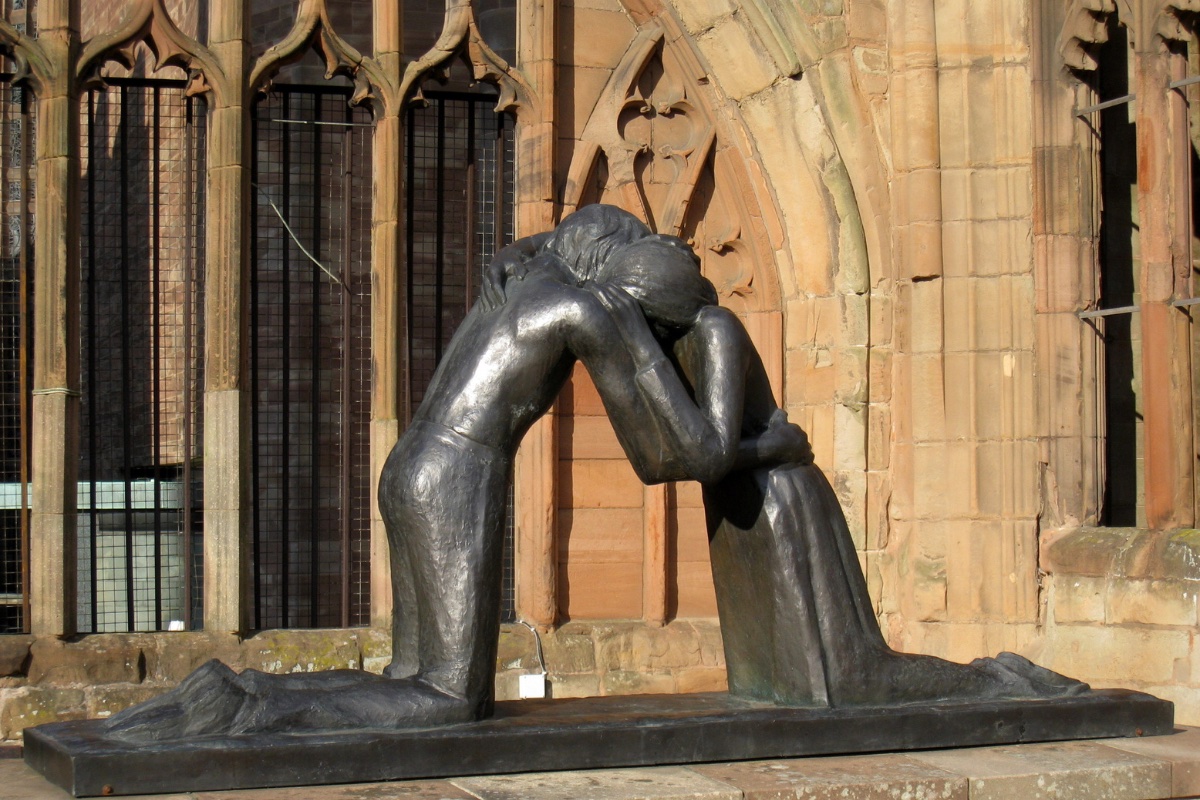

Photo credit: Courtesy of Gary Wayne Gilbert, Boston College.