Reconciliation is more than a response to conflict—it is a central part of God’s redemptive work in the world. These ten theses present reconciliation as a transformative journey, grounded in lament, sustained by hope, and oriented toward the holistic peace—shalom—of God’s new creation.

1. Reconciliation is God’s gift to the world. Healing of the world’s deep brokennessdoes not begin with us and our action, but with God and God’s gift of new creation.

When we neglect the story of God’s life and action, reconciliation may become popular, but its content will always remain vague. Christians often try to fix the brokenness of the world in a way that puts either us or the world at the center. In responding to the urgent needs of the world, our first question ought not to be, “What should we do?” but rather, “What is going on in the lives and the story of the world?” We begin with what God has already accomplished. The center of that story is Jesus.

“Therefore, if anyone is in Christ, the new creation has come...God was reconciling the world to himself in Christ” (2 Cor 5:17, 19 NIV).

When reconciliation is connected to God’s story and life, the invitation to be ambassadors of God’s reconciliation in the world is made clear and urgent.

2. Reconciliation is not a theory, achievement, technique, or event. It is a journey.

Scripture is central to the ministry of reconciliation because it both points to the specific end toward which the journey leads and shapes the path of our journey as we engage the deep brokenness of real places and lives. Without the unique stories of Scripture, we cannot cultivate the imagination necessary to live into the gifts and challenges of the journey of reconciliation.

3. The end toward which the journey of reconciliation leads is the shalom of God’s new creation—a future not yet fully realized, but holistic in its transformation of the personal, social, and structural dimensions of life.

A key question must always be, “Reconciliation toward what?” Reconciliation is not merely about getting along with neighbors or feeling at peace with God. It cannot be reduced solely to the personal or to the social dimension. It is not merely a political end to conflict nor mediation without healing. Reconciliation must never become a tool of the powerful to preserve the status quo. Rather, reconciliation is always a journey of transformation toward a new future of friendship with God and people, a holistic and concrete vision of human flourishing.

4. The journey of reconciliation requires the discipline of lament.

We say “discipline” because lament is the hard work of learning to see and name the brokenness of the world. To the extent we have not learned to lament, we deal superficially with the world’s brokenness, offering quick and easy fixes that do not require our conversion. The discipline of lament not only allows us to see the depth of the world’s brokenness (including our own and the Church’s complicity in it), it also shapes reconciliation as a journey that involves truth, conversion, and forgiveness.

5. In a broken world, God is always planting seeds of hope, though often not in the places we expect or even desire.

Reconciliation requires hope. But the ability to hope requires training. Hurried attempts at success in reconciliation can mask a desire to short-circuit the journey of reconciliation, revealing our inability to recognize and live with the signs of a new creation God gives. At the same time, it is easy to despair and give up hope in a broken world. The journey of reconciliation involves learning to see and embody signs of hope as well as training to live with hopeful patience in the sluggish present.

Reconciliation is always a journey of transformation toward a new future of friendship with God and people, a holistic and concrete vision of human flourishing.

6. There is no reconciliation without memory, because there is no hope for a peaceful tomorrow that does not seriously engage both the pain of the past and the call to forgive.

“Reconciliation without memory” and “justice without communion” are both failures to remember well—the first by forgetting the wounds of history, the second by forgetting the promise of resurrection and the call to forgiveness. A Christian vision of reconciliation provides resources to avoid both of these temptations by remembering the wounds in Jesus’ resurrected body.

7. Reconciliation needs the Church, but not as just another social agency or NGO.

Reconciliation is not the ministry of experts. It is God’s gift to “anyone in Christ.” Christians learn what it means both to be reconciled and to be ambassadors of reconciliation in and through the Church, which is called to be a “demonstration plot” of the social existence made possible by God’s gift of reconciliation. The Church’s vocation is to be an interruption of the story of division and violence in the world, participating with the ongoing work of the Holy Spirit pointing to the peace of God’s new creation. Without such interruption, we would not even know the alternative that is made possible by God’s new creation. To be a sign and agent of reconciliation, the Church must inspire and embody a desperate vocation of hope in broken places. We live in local places and in the everyday and ongoing practices of building community, fighting injustice, and resisting oppression while also offering care, hospitality, and service—especially to the alien and the enemy.

8. The ministry of reconciliation requires and calls forth a specific type of leadershipthat is able to unite a deep vision with the concrete skills, virtues, and habits necessary for the long and often lonesome journey of reconciliation.

We have many experts in reconciliation, but not many leaders. Reconciliation requires leaders rooted in God’s vision of the beyond who work patiently in the thick stubbornness of the now. Formation and conversion produce such leaders, requiring not only good mentors but also a lifestyle marked by prayer, courage, joy, and practical wisdom.

9. There is no reconciliation without conversion, the constant journey with God into a future of new people and new loyalties.

Broken by sin, we do not long for what God wants. The world and its dividing lines—such as nation, ethnicity, race, sex, power, and caste—resist the new creation of God’s beloved community, where there is “neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free man, there is neither male nor female” (Gal 3:28). Self-interest easily becomes the goal of relationships, and loyalty to one’s own group easily becomes the aim of politics. Reconciliation thus requires a transformation of desire, habits, and loyalties. This long and costly journey of conversion is impossible without God’s forgiveness and grace. But there is reason to hope: God has promised to give us everything we need for this transformation.

10. Imagination and conversion are the very heart and soul of reconciliation.

Reconciliation is about learning to live by a new imagination. God desires to shape lives and communities that reflect the story of God’s new creation, offering concrete examples of another way and practices that engage the everyday challenges of peaceful existence in the world. That is why the work of reconciliation is sustained more through storytelling and apprenticeship than by training in techniques and how-tos. Through friendship with God, the stories of Scripture and faithful lives, and learning the virtues and daily practices those stories communicate, reconciliation becomes an ordinary, everyday pattern of life for Christians.

Reverend Emmanuel Katongole is a priest of Kampala Archdiocese, Uganda, and professor of theology and peace studies. He holds a joint appointment with the Keough School of Global Affairs, where he serves as a full-time faculty member of the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies at the University of Notre Dame.

Chris Rice is an award-winning writer, social entrepreneur, and global networker dedicated to fostering social healing and spiritual renewal, grounded in his Christian faith. He co-founded the influential Duke Divinity School Center for Reconciliation.

Taken from Reconciling All Things, by Emmanuel Katongole and Chris Rice. Copyright © 2008 by Emmanuel Katongole and Chris Rice. Used by permission of InterVarsity Press, P.O. Box 1400, Downers Grove, IL 60515, USA. www.ivpress.com

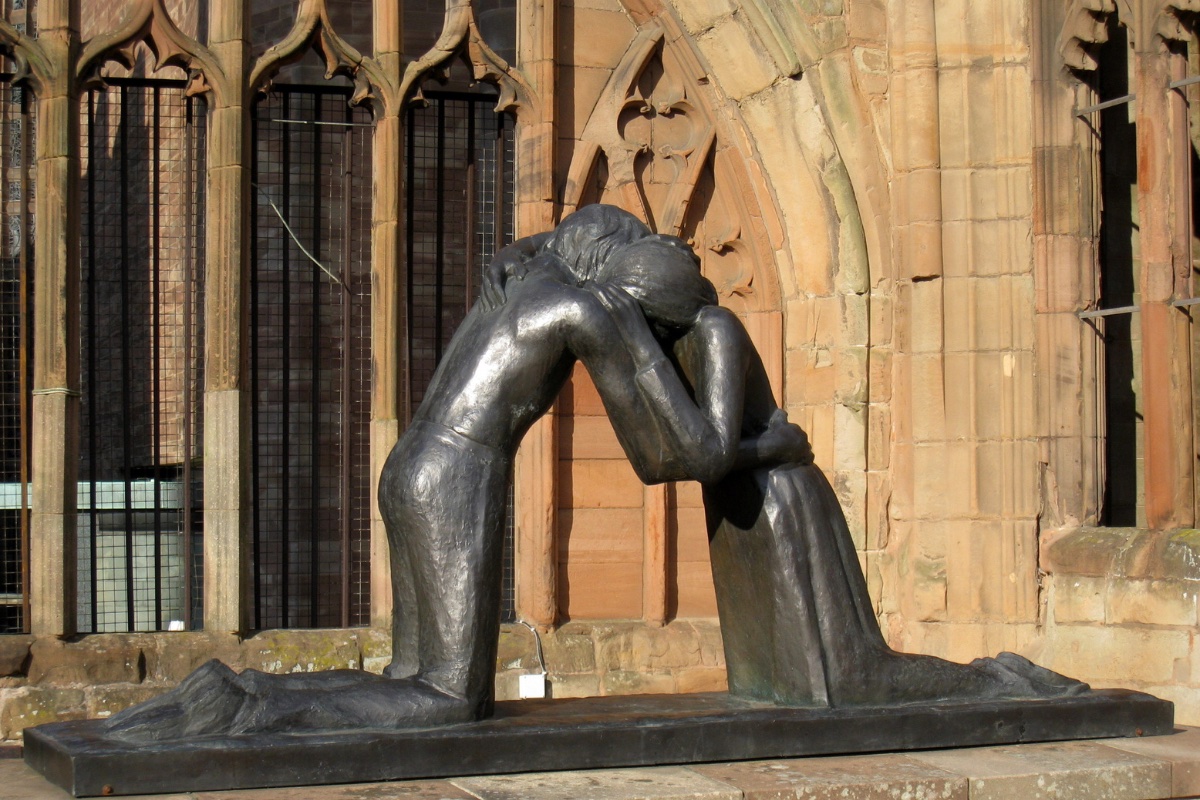

Photo: A winding road with a sunrise peaking over the hills.