Is it possible to reestablish a relationship that has been fractured by wrongdoing? The answer to this question might depend on who the involved parties are, the nature of their relationship, the magnitude of the harm inflicted, and whether there has been some form of redress to the wrongdoing. Reconciliation seems to be conditioned by a host of factors. Additionally, under certain circumstances reconciliation may not be attainable or even commendable. This edition of C21 Resources grapples with the complex nature of reconciliation and tries to offer readers some theological wisdom and prudential insights into its moral challenges.

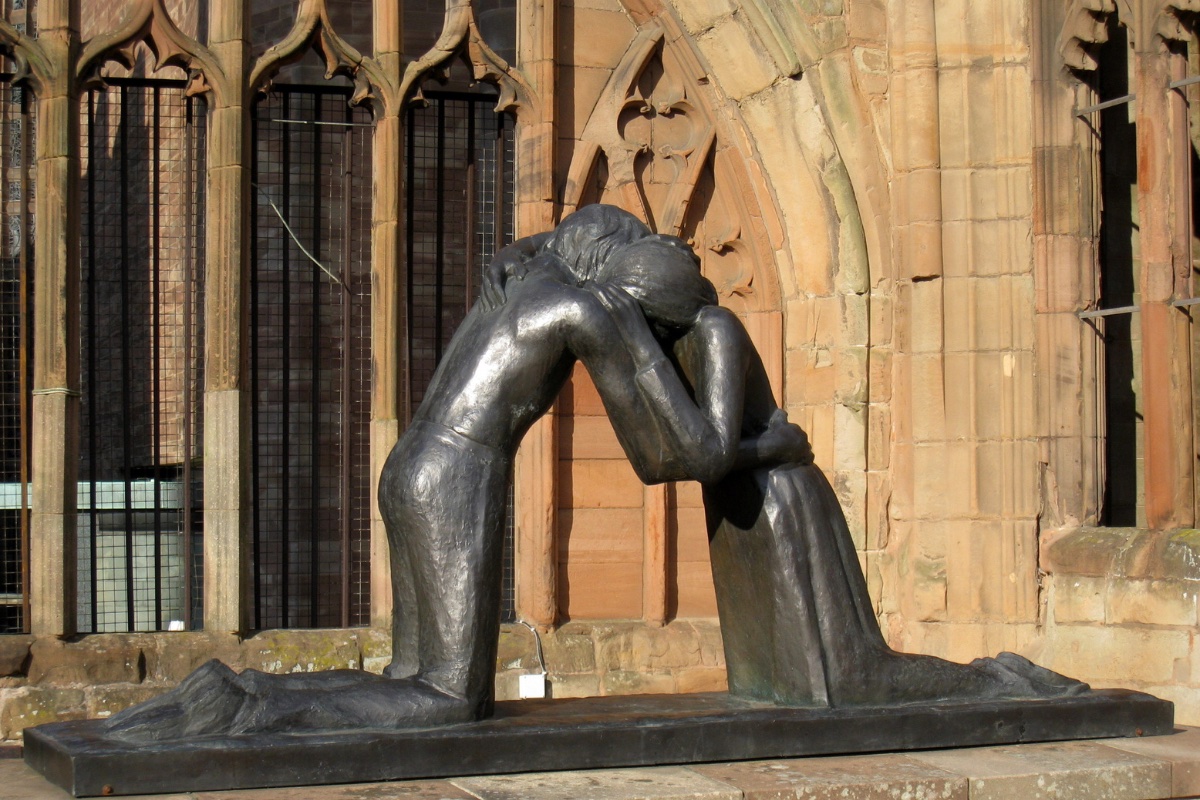

At the most basic level, reconciliation implies restoring relationships between people who have been alienated from each other. The parties involved in reconciliation are multitudinous. We can think of reconciliation collectively between God and humanity, personally between God and the believer through the Sacrament of Reconciliation, interpersonally between individuals that may or may not be well known to each other, socially between different groups within society, and politically between contentious political parties or adversarial regimes. Reconciliation can be understood as both a process and a goal. As a process, it is not a stand-alone concept. It is intimately connected to concerns for truth, justice, and forgiveness. As a goal, it is not merely conciliation, which occurs when former adversaries are willing to coexist without recourse to violence. The fullness of reconciliation is the reestablishment of right relationship with God, oneself, one’s neighbor, and all of created reality. Reconciliation is a willful process whereby the parties involved envision the hope of a shared future, rooted in trust, and a commitment to mutual well-being.

As the editorial board finalized this issue, the universal Church lost her Shepherd. Pope Francis died on Easter Monday, April 21, 2025. He lived up to the reputation of his namesake, St. Francis of Assisi, embodying the ministry of reconciliation as an instrument of peace. Through his outreach to those on the margins, whether it was visiting migrants in Lampedusa, washing the feet of incarcerated women and Muslim refugees, or calling for the end of violence in war-torn regions of the world, Francis demonstrated what reconciliation entailed. He desired a Church that included everyone, “todos, todos, todos!” This inclusive Church is a listening Church, a synodal Church.

Dialogue was essential to Francis’ understanding of reconciliation. In his Angelus on July 20, 2014, the pope pleaded, “May the God of peace arouse in all an authentic desire for dialogue and reconciliation. Violence cannot be overcome with violence. Violence is overcome with peace!” Again, Francis commended us to “respond to violence, to conflict and to war, with the power of dialogue, reconciliation and love” (Angelus, September 1, 2013). For Francis, open and honest dialogue, acknowledgment of wrongdoing, and a willingness to amend past injustices are the pathways to reconciliation.

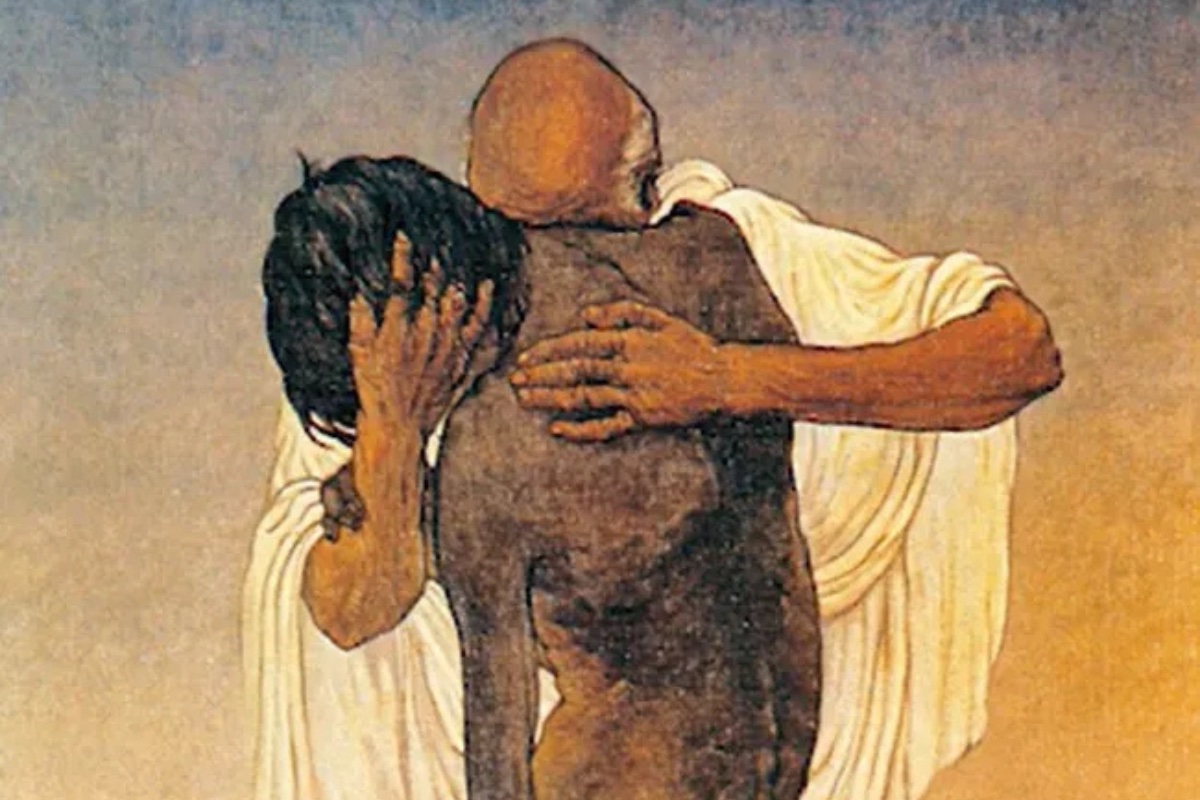

The work of reconciliation is not merely a human endeavor, but a divinegift flowing from the crucified Christ. According to Francis, it is in the silence of the cross that “the uproar of weapons ceases and the language of reconciliation, forgiveness, dialogue and peace is spoken” (Homily, September 7, 2013). Furthermore, “if we want to be reconciled with one another and with ourselves, to be reconciled with the past, with wrongs endured and memories wounded, with traumatic experiences that no human consolation can ever heal, our eyes must be lifted to the crucified Jesus; peace must be attained at the altar of his cross” (Homily, July 25, 2022). Reconciliation is a grace that radiates from the love of God embodied on the cross. Through the grace of reconciliation, hatred is transformed into love and division is overcome through unity.

The fullness of reconciliation is the reestablishment of right relationship with God, oneself, one’s neighbor, and all of created reality.

Following nine days of mourning, the world waited and wondered who would emerge from the conclave as the new pope, and whether he would continue the legacy of Francis. Mostof the world was surprised when Cardinal Robert Francis Prevost, a Chicago native and former Bishop of Chiclayo, Peru, was named the two hundred and sixty-seventh head of the Catholic Church. In choosing the name Leo XIV, was the new pope shedding light on what direction hispontificate might take? Would he be like Leo XIII who, in writing the encyclical Rerum novarum, ushered in the era of Catholic social teaching? Or would he be a peacebuilder likeLeo the Great, who convinced Attila to spare Rome in 452?

On May 8, 2025, the first Augustinian and U.S.-born pontiff, Pope Leo XIV, addressed the faithful with these words: “Peace be with you all... It is the peace of the risen Christ. A peace that is unarmed and disarming, humble and persevering. A peace that comes from God, the God who loves us all, unconditionally... Help us, one and all, to build bridges through dialogue and encounter, joining as one people, always at peace.” With this statement, Pope Leo XIV declared the need to continue the ministry of reconciliation through dialogue and the promotion of peace. As an Augustinian, Pope Leo XIV knows that peace is not merely the absence of conflict, but the comprehensive answer to our greatest social needs. In The City of God, St. Augustine defined the peace of all things as “the tranquility of order.” Peace begins with an internalized transformation of the heart that results in harmony and order within oneself. It is the grace of the risen Christ that transforms the inner depths of the human soul.

Augustinian peace is not simply contemplative, but an internal disposition that must be possessed in the heart, loved in action, and lived through justice. Peace is gradually realized in the outward movement of the individual into broader levels of interpersonal, social, and political right relationship. Right relationships are constituted by harmonious concord achieved through charity and justice. Peace is pluralistic and dynamic, involves multiple relationships, and entails human flourishing within a communal context, having religious, social, economic, and political dimensions.

The Church has a unique responsibility to promote peace through reconciliation. As the people of God, the Church is a community reconciled with God through the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus and called to be ministers of forgiveness and reconciliation. It is a sacramental community mediating peace and reconciliation. Reconciliation requires people of goodwill to constructively engage conflicts in order to move beyond polarization and division. In the Fall 2023 issue of C21 Resources, guest editor Brian Robinette curated a collection of articles that diagnosed the dynamics of polarization and offered practical guidance for addressing it. The current issue builds on this foundation by exploring the complex reality of reconciliation as a response to conflicts and division.

The articles featured offer a diversity of perspectives ranging from theologians, academics, public intellectuals, and peacebuilders, to students and alumni. They offer collective wisdom about what reconciliation means and the processes it entails. They challenge us to critically reflect upon where reconciliation is needed most: relationships strained by abuse, betrayal, mental illness, or infertility; division over the global migrant crisis; lives devastated by mass incarceration; and countries torn apart by war. Moreover, they offer prudential guidance for when reconciliation is appropriate and what practical steps can be taken to achieve it. After examining this issue, perhaps our readers might feel inspired to return to the Sacrament of Reconciliation, call an estranged friend or family member, get involved with their local parish to promote peace and justice, or petition their political representatives to bring an end to areas of conflict throughout the world.

Guest Editor, Joshua R. Snyder, Ph.D. '15, is associate professor of the practice in theological ethics at Boston College. He also is the director of the Faith, Peace, and Justice minor. Joshua earned his Ph.D. in theological ethics from Boston College in 2015. His dissertation, Love Promoting Justice: An Augustinian Ethic for Transitional Justice from the Context of Guatemala, explored how charity as a civic virtue can bring about social reconciliation in a divided society. Joshua’s research focuses on transitional justice and Catholic peace-building with an emphasis on the Guatemalan Catholic Church & human rights.

Photo credit: CNS photo/Paul Haring. Pope Francis greets refugees who are traveling to Rome with him at the international airport in Mytilene on the island of Lesbos, Greece, April 16, 2016.