Does a war really end once fighting stops? Even after battles are over, the effects of war can last for generations. Consider a postwar society where people continue to harm each other for revenge or other reasons, all of which lead to a dysfunctional society and threaten human security. As wounded bodies lie in the streets again and people fear recurring violence, we must ask how best to establish a just and sustainable peace following violent conflict.

According to both the Peace Agreements Database (PA-X) at the University of Edinburgh and the Peace Accords Matrix (PAM) at the Kroc Institute of the University of Notre Dame, while partial peace accords, such as ceasefires, have an 85% rate of conflict relapse, comprehensive peace accords, which go beyond the end of violence to include human security and political reconciliation, have a 14% rate of conflict relapse. For example, if we want to preserve the sovereign nation of Ukraine and prevent further human suffering, a comprehensive peace accord could be a more just, legitimate, and effective direction than its counterpart at least from a jus post bellum (jpb, postwar justice and peace) perspective.

There is a wide range of discourse on jpb ethics. One popular approach is the restricted, or minimalist, position, grounded in the just war tradition. Historically, this tradition has focused on two categories, jus ad bellum (right to wage war) and jus in bello (just conductin war). However, growing attention is now given to how war ends and what follows, particularly the moral quality of postwar reconstruction as a determinant of a war’s over justness. Within this context, some scholars highlight jus terminare bellum—the principles guiding the responsible termination of conflict or the responsible use of force to end hostilities—as a distinct phase. While jus terminare bellum addresses how a war is concluded, jpb focuses on the postwar transition and the establishment of a just peace in the immediate aftermath of war. Though related, they mark separate but complementary aspects of just war theory.

Another emerging approach is the extended, or maximalist, position, which seeks for a broad comprehension of postwar justice that may include various civil society peacebuilding actors to support reconstruction, so as to ensure a comprehensive peace accord that aims for human security and political reconciliation. Hence, jpb is a set of legal, political, and moral principles that guide the transition from war to peace as it includes the establishment of just policing (e.g., fair law enforcement ensuring safety for both peacekeeping and nation building), the establishment of just punishment (e.g., holding criminals accountable while allowing rehabilitation), and the establishment of just political participation (e.g., inclusive governance for a stable society). As the twenty-first century’s postwar conflicts in the Middle East, Central Africa, the Balkans, and elsewhere wind down, we have witnessed that in the immediate aftermath of war, there has been little or no policing, punishment, or avenues for political participation to protect the lives of people, especially those most vulnerable. Furthermore,the need for jpb scholars and practitioners across various disciplines to elaborate and apply norms of postwar peacebuilding to assessment of reconstruction policies—of just policing, just punishment, and just political participation—have grown more apparent. Therefore, a more balanced understanding of jpb must pay direct attention to the elements comprising human security in a postwar context as well as the quest for political reconciliation. Certainly, reconciliation ought to be among the norms just actors employ as long as it serves the jpb’s primary and foremost mission of human security.

...as emphasized with the importance of comprehensive peace accords, long-term peace cannot be achieved through punishment and security measures alone; rather, it must include a commitment to reconciliation.

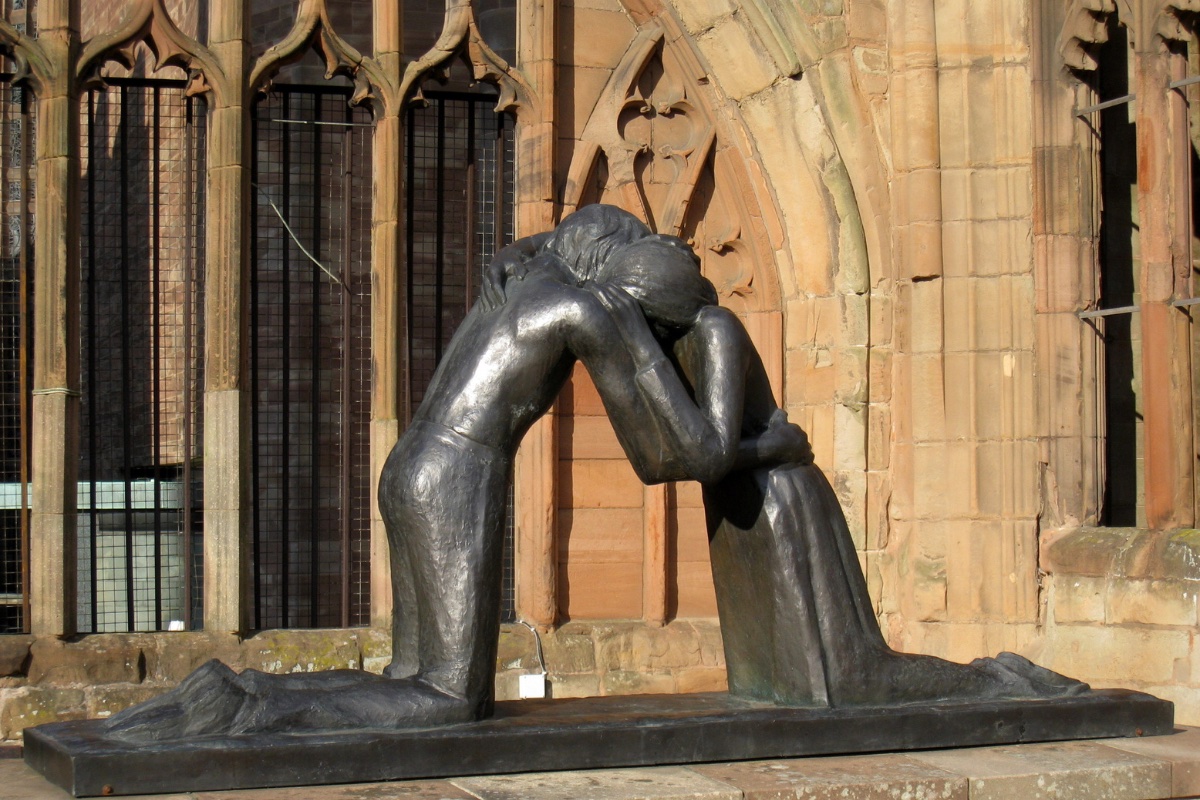

Human security is the most fundamental characteristic included within peace accords and is found in 85% of the accords listed on PA-X: “Beyond a suspension of hostilities and affiliated prohibited actions, human security provisions deal with collaborative endeavors such as disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration of insurgent forces, and the reform of existing security forces.” But also, as emphasized with the importance of comprehensive peace accords, long-term peace cannot be achieved through punishment and security measures alone; rather, it must include a commitment to reconciliation. This viewpoint shifts the focus from state-centric approaches to justice toward a more inclusive and human-centered vision of postwar recovery. I want to highlight the tendency of postwar societies to focus on legal retribution and security enforcement, often at the expense of social healing and reconciliation, which can perpetuate cycles of violence. An example of this is the post-invasion Iraq strategy, which excluded former Ba’ath party members and other Sunnis from governance, ultimately fueling insurgency and prolonged instability. Reconciliation is not merely about moving on but addressing woundsthat, if left untreated, may continue to fester and divide societies. It is not about excusing past crimes but rather creating an environment where former enemies can coexist and rebuild trust.

Further, Christian ethicists Mark Allman and Tobias Winright categorize reconciliation as one of the four jpb phases that function as restorative justice—transforming the relationships of the belligerents from hostility to tolerance, leading to postwar justice tempered by mercy. This restorative justice transforms relationships from hostility to peace. Political scientist Daniel Philpott develops it into the notion of political reconciliation rooted in the monotheistic religious traditions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, where pursuing justice demands political reconciliation through mercy and peace. He is inspired by advocates of restorative justice, who typically look beyond modern Western law and justice to the ubuntu ethic of sub-Saharan Africa, sulh rituals in the Islamic tradition, and certain strands of Christian theology, especially both the historic peace church tradition and the recent Catholic nonviolence and just peacemaking movements. He proposes an array of practices that seek to restore right relationships. These practices are composed of six more nonviolent-leaning jpb elements: the building of socially just institutions, acknowledgment of suffering caused, reparations, accountability, apology, and forgiveness. These elements are independent and complementary. The ultimate intention of the ethic of political reconciliation is not only to redress a different set of wounds of political injustice in a distinct and nonviolent way but also to restore a dimension of human flourishing and just political order.

Political reconciliation must coexist with human security to restore justice and social harmony. Plainly, human security is fundamental but also interdependent to political reconciliation as it paves the way for long-term social restoration of participatory government and cooperative institutions. As introduced in my book Justice after War, if human securityis fulfilled, a long-term effort more than a minimalist version of jpb must be imposed. Efforts include “calling upon transitional justice, moving from the phase in which armed forces are in charge of just policing to the phase in which a non-military civilian force, namely police, is in charge of just policing.” Accordingly, postwar policies should focus on securing human dignity and political participation before attempting broader societal transformations. While idealistic models of postwar justice often aim for full democratic reconstruction, I believe that in the immediate aftermath of war, basic security and trust building must be a priority. This idea is very relevant, considering how high the failure rate of peace accords is. Many of these agreements fail due to an overemphasis on institutional reform without addressing various levels of security and reconciliation, including grassroots and local community based.

David Kwon, Ph.D. ’18, is assistant professor of theology and religious studies at Seattle University. He is the author of Justice after War: Jus Post Bellum in the 21st Century (Catholic University of America Press, 2023).

Photo credit: UN Photo/Marco Dormino