The church always seemed different when the boy went to confession. To begin with, most of the lights were off, a shadowy contrast to the brightness of Sunday mornings. Off in a corner, a solitary red sanctuary lamp flickered, and there were several racks of small votive candles, only about half of them lit at any one time, just inside the altar rail. The natural light of the afternoon sun came through the stained glass windows from outside, and he could stare at the radiant scenes, imagining himself into the stories they depicted: the adolescent Jesus instructing the astonished elders in the Temple, the hesitant Peter sinking into the sea while Jesus stood serenely on the waves. The smells of Sunday were gone too, the pungent incense and the sweetness of flowers having grown faint after a week’s time. Now, his nose detected only the varnish that made the wooden pews shine, particularly on the ends, each one topped by an ornate carved fleur-de-lis. Above all, the place was quiet. No matter how many people, young and old, were there—as few as a dozen, as many as fifty—they all kept silent, absorbed in their own thoughts and averting their eyes from one another. It was a curious sensation: somehow, he was alone in public.

He took his place in a pew on a side aisle, kneeling to say some silent prayers. Periodically, he would get up and move to the pew ahead of him once that one had been vacated by its previous occupant, everyone successively inching closer to the small enclosure, like an oversize box, that stood out from the side wall. There was a door in the middle of it, and on either side an open archway, covered by a curtain, into which the waiting parishioners disappeared, one after another, reemerging a few minutes later. By the time he got to the head of the line, the boy’s random thoughts had begun to focus. He had decided—rehearsed, really—what he was going to say to the priest who, he knew, occupied the center compartment. Just as important, he had decided what he was not going to say. When it came his turn, he walked purposefully, went in behind the curtain, and knelt down. He could hear the little click of the electrical switch in the kneeling pad that turned on the light above his entryway outside, alerting others to his presence so they would not burst in unawares. He waited in silence, conscious of indistinct murmurs as the priest talked with the person in the opposite stall. He knew he was not supposed to make out what they were saying, and he was seldom tempted to try, more concerned with last thoughts of what was about to happen. Then, at once, the wooden panel covering the window that separated him from the priest slid open, sometimes with a soft bang. The window was covered with an opaque plastic shield, making it possible for him and the priest to hear but not to see one another.They were both in darkness.

...without dwelling on the idea or even quite understanding how, they nevertheless believed that something important had just happened to them...

The boy began by crossing himself and reciting the words he had first learned in the second grade: “Bless me, Father, for I have sinned. It has been two weeks since my last confession, and these are my sins.” Then he launched into his brief catalog, specifying the things he had done wrong and the number of times, according to his best recollection, he had done each of them. They were pretty much the same from month to month, year to year. He didn’t snitch money from his mother’s pocketbook, and he mostly followed his father’s good example in not cursing, but there were always squabbles with siblings and schoolmates to report. Over time, he had developed some lawyerly skills, consolidating a number of miscellaneous offenses into the single category of disobedience. His reasoning, he thought, was ironclad. His parents may not have known that he was doing these things, but they would have forbidden them if they had; this constituted a form of implicit disobedience. Better to confess that than to recount potentially more graphic details. When he had finished his list, again following the formula, he concluded by saying that he was sorry “for these and all the sins of my past life.” The priest might then ask a clarifying question or two—the boy’s later memory was that this did not happen very often—and he would usually give a word of advice or encouragement to do better in the future. After that, the priest assigned what was called a penance, a kind of punishment, far from onerous but necessary for forgiveness to be complete. Finally, as the boy recited aloud the prayer known as the Act of Contrition, the priest whispered the words of absolution in hasty, mumbled Latin, which the boy could not really hear and would not have understood if he could. He also vaguely discerned the priest’s silhouette making the sign of the cross in his direction. With that, it was over. The slide closed again, and the boy went back outside, his place taken by the next person who had been waiting, setting off another chain reaction in the pews.

Not looking around, he walked up to the altar rail at the front of the church, knelt there, and silently performed his penance. Usually this consisted of some combination of the fundamental Catholic prayers, the “Our Father” and the “Hail Mary,” repeated for perhaps three to five times each, depending on the priest’s instructions. If he had a dime in his pocket, he might slip it into the slot and then light one of the votive candles; there was always a little thrill that came from playing with fire in this permissible way. Then he was done. He went back outside to wait for those others in the family who had come along that day. They did not speak about what they had just done, simply going home to Saturday night supper. But without dwelling on the idea or even quite understanding how, they nevertheless believed that something important had just happened to them, that they were different now from what they had been earlier in the day, that they were reconciled with God in spite of their human failings. It was a remarkable thing.

James M. O'Toole is professor emeritus and Clough Millennium Chair in the history department at Boston College. He also serves as the University historian.

Excerpted from For I Have Sinned: The Rise and Fall of Catholic Confession in America, published by Harvard University Press. Copyright ©2025 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

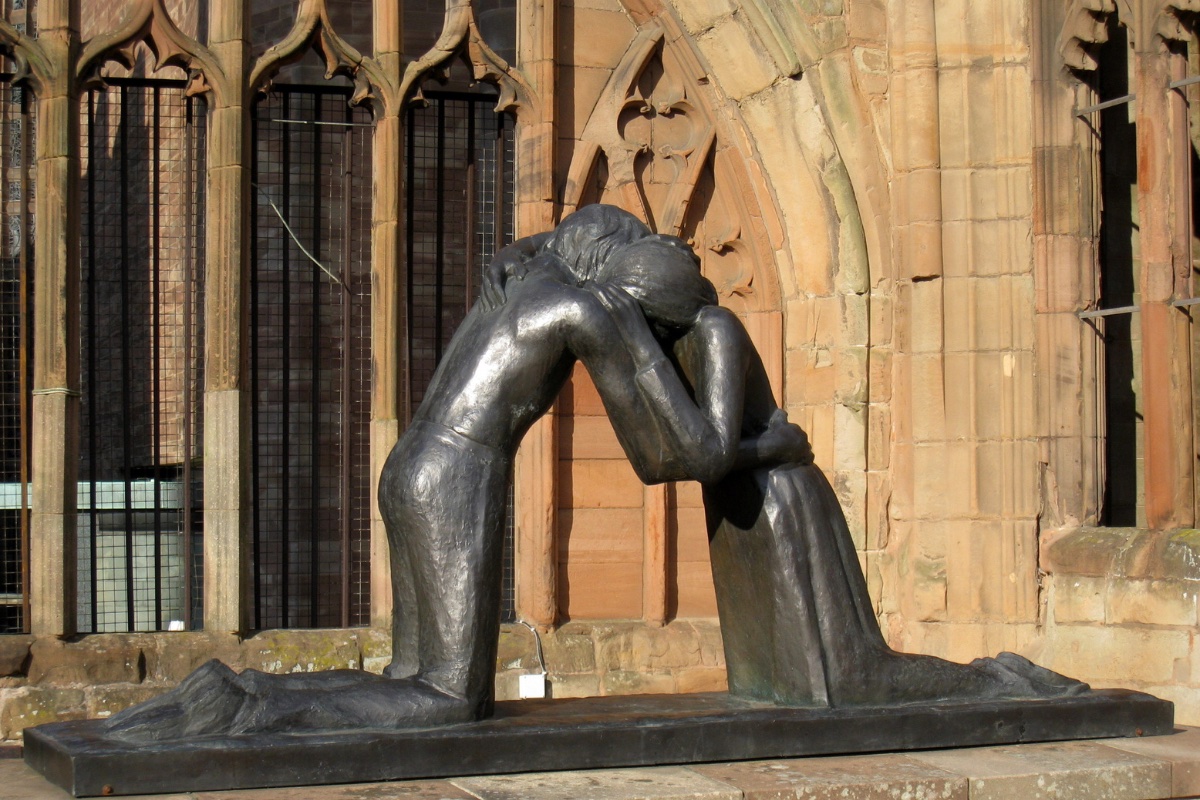

Photo credit/description: Andrew Craig, '17, MATM '19. Confessionals behind the wooden sculpture of Jesus in St. Mary's Chapel, Boston College.

The Act of Contrition

My God, I am sorry for my sins with all my heart. In choosing to do wrong and failing to do good, I have sinned against you whom I should love above all things. I firmly intend, with your help, to do penance, to sin no more, and to avoid whatever leads me to sin. Our Savior Jesus Christ suffered and died for us. In his name, my God, have mercy.