By

For more than a year, Professor of Sociology Sharlene Hesse-Biber would regularly leave Boston College on Fridays to make a bittersweet journey, traveling to Virginia to help care for her youngest sister, Janet, who was dying of breast cancer.

Few, if any, of her colleagues or friends at BC knew this. Nor did many of them know Hesse-Biber herself had battled breast cancer twice, or that her older sister and her mother were going through the same struggle.

Hesse-Biber’s reticence might seem uncharacteristic for someone whose academic career has been marked by outspokenness on women’s health issues, particularly the impact of sociocultural factors on women’s body image.

“When it comes to my personal life, I am a private person,” explains Hesse-Biber. “And there was so much happening at once in our family, I didn’t want to deal with it publicly. But after Janet’s death, I felt I wanted to give back some of my skills as a researcher and writer, and use them to talk about the impact of cancer on families and individuals.”

One aspect of this experience loomed large for Hesse-Biber. When she was diagnosed a second time, her physician suggested she undergo testing to see if she had the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutations, which increase the risk of breast and ovarian cancer. Hesse-Biber and her older sister took the BRCA test, and results were negative for both.

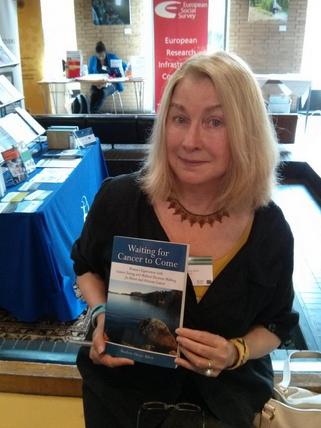

Yet for Hesse-Biber, the BRCA testing raised a host of ethical, moral and social-justice questions, and sparked a curiosity about how women coped with these and other issues related to cancer. Her recently published book, Waiting for Cancer to Come: Women’s Experiences with Genetic Testing and Medical Decision Making for Breast and Ovarian Cancer, is the first to explore the complicated emotional, social, economic and psychological turmoil these women face.

Based on interviews and surveys of more than 60 diverse women, Waiting for Cancer to Come uses their voices to describe the under-explored BRCA experience, from family crises, secrets and revelations to difficult surgeries and personal empowerment. After introducing the genetic testing culture, each chapter follows the experiences of women from their decision to be tested, through their positive mutation finding, to dealing with their risk.

Hesse-Biber says it is important to put the women’s experiences in a broader context. Undergoing the BRCA test brings the individual in contact with a for-profit industry that may not always have a customer’s best interests in mind, and which claims exclusive ownership of the medical or personal information it obtains through the BRCA tests. What’s more, she adds, the route from one industry usually leads straight to another: the surgical industry, with its own set of interests and practices that don’t necessarily work to a patient’s benefit.

“What you face is a sales pitch that uses fear and guilt: ‘Take this test or you might never know’; ‘Have the surgery or else you’ll get cancer – or you might pass it on to your kids,’” Hesse-Biber explains. “This is not to advocate against testing or surgery. But the problem is, testing and surgery are expensive and time-consuming, and there are so many things a woman may not know or be prepared for.

“If you’re a woman in her 20s who’s a BRCA-positive mutation carrier, how do you tell your boyfriend? When you have a double mastectomy, the average recovery time is 18 months – it’s not like Angelina Jolie [who had a double mastectomy in 2013 after discovering she was BRCA-positive], where you come out smiling like nothing happened. What if you have a surgeon who does a ‘one-size-fits-all’ reconstruction? Will your husband or partner and friends be there for you, or will they bail out? And will the cancer really be gone?

“I asked Cassandra, who has Stage 4 cancer, what life was like for her. She said, ‘It’s about living for the next medicine, because when you stop, your time in Dodge City’ – that was how she and other patients referred to treatment – ‘is about up.’”

Hesse-Biber has now expanded her project to include men who are BRCA-positive, a population that is practically invisible to American society but no less in need of attention.

“Five hundred men a year die from breast cancer, and there are many more we don’t know who have BRCA, which can lead to prostate or pancreatic cancer,” says Hesse-Biber, who expresses gratitude to the University for its support of her work, especially through the Undergraduate Research Fellows program.

Meanwhile, Hesse-Biber’s own BRCA-related story continues favorably: Although they still mourn the loss of Janet, she, her sister and mother are all doing well, she says.

“I don’t research something if I don’t feel it will make a difference,” she says. “While it’s true I have a personal stake in this area, this project is not about me; it’s about women like Cassandra, and how their lives can be empowered.”

For more on Hesse-Biber’s research, including a podcast series companion to Waiting for Cancer to Come, see her website at hessebiber.com.

-–Patricia Delaney contributed to this story