By

Seminal moments from the first 150 years of Boston College have been captured in words and images in the newly published book, The Heights: An Illustrated History of Boston College, 1863–2013, written by Office of Marketing Communications Executive Director Ben Birnbaum, special assistant to the president and editor of Boston College Magazine, and Institute for Advanced Jesuit Studies Assistant Director Seth Meehan, with photography by Gary Wayne Gilbert, OMC director of photography.

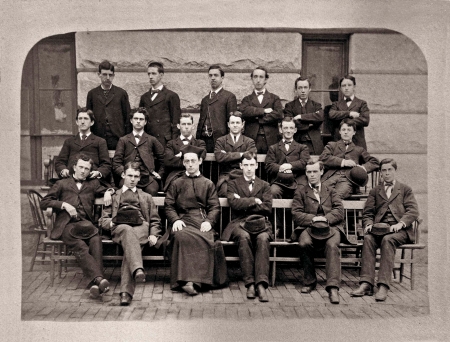

Expertly researched, The Heights (published by Linden Lane Press), which includes information and photographs never previously published, tells the Boston College story from before it opened with 22 students in 1864 to its rise as a leading national university with students from across the country and the globe. As the introduction states, “These heights were neither inevitable, foreseeable or even conceivable at its founding (and most of the way to 2013).”

Meehan pored over more than a dozen archives in Massachusetts, Washington, DC, and Rome. Some of the archival material was previously sealed and had not been available to earlier writers of Boston College histories.

Beyond the monumental scope of the project, one of the biggest challenges facing the authors, according to Birnbaum, was “finding the real story behind the history we thought we knew.”

Added Meehan, “It was a challenge to reconcile the rather potent mythologies that surround Boston College and its history with the materials that we found in the primary sources. Often, widely told stories were either not supported or contradicted with what we found in the archives. I came back [from Georgetown] with letters that previous historians did not use and that changed the story slightly.

“That was the case with [BC founder] John McElroy, SJ, the founding of the school, and Boston College’s first years in general. After Georgetown, Ben and I recognized the need to go back to as many archival sources as possible. Each place yielded insights that were new and important to us.

“I hope that readers appreciate the visual aspect of the book. I get lost in the photographic arrays constructed by Gary Gilbert, especially those on World War II and coeducation,” said Meehan. “I personally hope that readers will look at the images and read the essay of a particular topic or two, become interested to know to more, and visit the archives. There is so much more that is not in our book, and plenty left to discover.”

“It was challenging to bring life and vibrancy into hundreds of historical images, many of which in their original form were faded and worn,” said Gilbert, who served as art director for the project. “What I hoped to achieve through the still-life constructions was a more dramatic visual sense of life during the early days of BC’s history.”

The Heights, Birnbaum says, is about “foundational turning points for Boston College, pivot points where, without something happening, the University would have gone in a different direction.”

Birnbaum points to three moments when “BC could have disappeared”: World War I, World War II and 1970-71. The war years were marked by plummeting enrollment. With so many men entering military service, the number of students dipped to 236 in 1944. “God knows if BC would have survived had the war continued another couple of years,” he said.

The early 1970s saw a deep budget deficit, striking students, petitions, rising tuition and student takeovers of Gasson Hall and the President’s Office, combined with general American tensions over the war in Vietnam and race relations, all of which created a tumultuous time on the campus.

When asked which Jesuits (living Jesuits excluded) would appear on Boston College’s version of Mount Rushmore, Birnbaum chose Fathers John McElroy, Robert Fulton, Thomas Gasson and Michael Walsh.

Fr. McElroy was “stubborn” and “driven” about making his dream of a Jesuit school in Boston a reality. Fr. Fulton, BC’s first academic dean and a two-term president, brought “intelligence and perspective.” Fr. Gasson, who was responsible for the University’s move to Chestnut Hill, “changed the whole game.” Fr. Walsh, president from 1958 to 1968, “drove BC to the cusp of something great.”

While BC’s history is about great leaders, it is also about “bit players,” noted Birnbaum, citing the essay on Richard A. O’Brien, SJ, an athletics director (1916-1924) whose 90-page photo album resides in the University Archives, and the anonymous alumni who appear in many of the book’s photographs. “I admire them. They have given this place structure and wisdom.”

Birnbaum, who has worked at BC since 1978, said the most surprising discovery for him was the story of the underappreciated William Keleher, SJ, president from 1945-1951. During his tenure, Fr. Keleher purchased the 37.5-acre reservoir that became Lower Campus, erected three buildings (Fulton, Lyons and the service building), broadened the curricula and increased academic requirements for faculty. He also welcomed returning World War II veterans as students under the GI Bill, a decision not all associated with the University supported. Enrollment rose from 2,000 to 7,000 students.

“It’s very seldom that excellent people are overlooked, but that’s the case with Keleher. Considering all he accomplished, it astonishes me he is not more highly regarded,” said Birnbaum.

The Heights spotlights other unsung people in BC’s history, such as Mary Roberts, president of the Philomatheia Club, an all-women support group of Boston College. “She was literally the development office,” said Birnbaum. “When people needed something they turned to Mary and her crew.” The authors call Roberts “the most influential woman to participate in [Boston College] life during the first 100 years of its existence.”

Said Meehan, “I think it is important to profile the once indispensable and now largely forgotten individuals in Boston College’s history because by rediscovering what they did, why they did it, and what made them so important to the institution, you can better understand the institution and the culture at the time.

“For a half-century, Mary Roberts led one of the most — if not the most, without qualifier — important organizations in Boston College’s history, and for most of her leadership, her members could not attend the school they so enthusiastically supported. That says something to me about what the local community thought of the value of Boston College.

“And for Keleher, it is easy to think that the rise of Boston College after World War II was somehow inevitable. But he, Roberts, Cardinal [Richard] Cushing and others at Boston College made particular decisions to push the University forward.”

Meehan, who completed the book while also finishing his doctorate in history at BC, expressed personal gratitude to History Department faculty members James O’Toole, Lynn Lyerly, Owen Stanwood and Kevin Kenny, as well as to Provost and Dean of Faculties David Quigley, University President William P. Leahy, SJ, and the OMC staff, including Assistant Director Keith Ake.

Birnbaum is quick to credit the extraordinary work of University Archivist Amy Braitsch. “We couldn’t have done this without her,” he said.

One revelation for Birnbaum that he hopes readers will share in is “that from the beginning BC has had a sense of community, a sense of family. There may be fighting like there is among family members, but there is also wonderful affection.”