By

Two seminal 19th-century works – both significant in the evolution of American thought and writing, but rarely considered in relation to one another – are the focus of a Burns Library exhibition opening this month, “Nathaniel Hawthorne and Frederick Douglass: Texts and Contexts.”

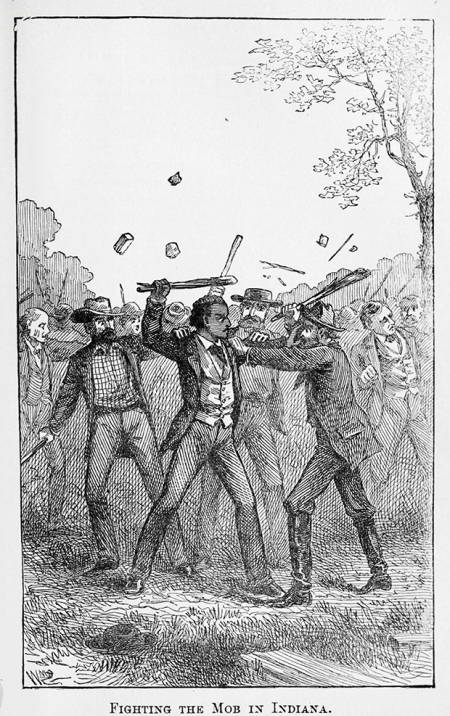

The exhibition, on display from Oct. 15 through Jan. 24, showcases Hawthorne’s The Blithedale Romance (1852) and Douglass’ “The Heroic Slave” (1853). Blithedale, Hawthorne’s third major novel, is set in a utopian socialist community that is undermined by the self-interested behavior of its members. Douglass’ novella follows the development of an enslaved man who first escapes from bondage and then leads a rebellion on board a slave ship.

These strikingly different works were released six months apart by publishers located on the same block in downtown Boston.

“While Hawthorne’s novel is meditative and ambiguous and Douglass’ story is direct and argumentative, each draws on actual events and features characters who attempt to reform or escape unjust systems,” explains Professor of English Paul Lewis, the exhibition curator.

“Juxtaposed, the works suggest different ways in which literature absorbs, reflects, engages and contributes to contemporaneous social, economic, political, and cultural life.”

[Burns will host an opening reception for the exhibit on Oct. 21 at 5:30 p.m.; for information, call ext. 2-4861.]

The exhibition comprises some 30 original works from the Burns Library’s Boston Collection, in addition to reproductions of engravings and paintings lent by other institutions. A bound volume of The Liberator, an abolitionist newspaper founded in 1831, was borrowed from Providence Public Library, according to Burns Librarian Christian Dupont, associate University librarian for Special Collections.

Among the works on display are first or early editions of Douglass’ autobiography and Hawthorne’s fiction, Lewis said, and works by such writers as Louisa May Alcott, T.S. Arthur, Lydia Maria Child, W.E.B. Dubois, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Olaudah Equiano, Margaret Fuller, Harriet Jacobs, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Henry David Thoreau, David Walker, Booker T. Washington and Phillis Wheatley.

The display grew out an advanced topic seminar for English majors on literary Boston from 1790 to 1860, taught last spring by Lewis. For one assignment, students researched a specific context – such as women’s rights and temperance reform for Hawthorne’s novel, and abolitionism and representations of the heroic for Douglass’ story – and related texts and images that could illustrate these ideas in an exhibit. Lewis then worked with English Department doctoral student Scott Reznick, the display’s associate curator, to develop the exhibit.

“In many respects, Frederick Douglass and Nathaniel Hawthorne could not be more different,” Reznick said. “Douglass was a black abolitionist ardently committed to social and political reform while Hawthorne harbored conservative viewpoints. Yet both exhibited an ability to think deeply about what it meant to live in an era of unrest. I hope viewers come away with an appreciation for the way two writers, who seem to have few similarities, wound up crafting imaginative responses to a similar set of concerns,” he added.

Placing these works in wider contexts, the curators note, conjures up the world in which they were written and with which they were deeply, if differently, engaged. The array of writers and thinkers represented in the exhibit underscore important elements of the complex historical moment in which Douglass and Hawthorne lived and wrote.

“Just seeing this remarkable collection of American books is illuminating,” according to Lewis. “At a time when texts are often accessed electronically, looking at first and early editions is a form of time travel that connects us to the experience of their first readers. Beyond this, each of the two main works is surrounded by others that highlight the complex and varied interconnectedness of literature, politics, and culture broadly defined.”