By

Pow! Zap! Wham! Kaboom!

Cold War! Watergate! Women’s Liberation! 9/11!

Comic books have never just been about super-powered heroes in skintight costumes whose exploits are depicted with vivid illustrations and onomatopoeic words. Scholars, commentators and journalists alike have shown how, in and amongst the pages of Superman, The Avengers, Wonder Woman and Spiderman, lurk often fascinating snippets about American life, offering X-ray vision-like insights into societal and cultural shifts.

Now, a group of Boston College undergraduates has contributed its own perspective on the deeper messages conveyed by comic books, with a project that includes a just-opened exhibition in Stokes Hall. “Revealing America’s History Through Comics” was created by students in the Making History Public class taught by Professor of History Heather Cox Richardson, working with Justine Sundaram, reference librarian at the John J. Burns Library.

Using popular Marvel and DC titles from the 1940s through present day – from an immense collection donated to Burns Library by Carroll School of Management Professor Edward J. Kane – the students examine a range of cultural themes and trends in comic books reflecting major historical events and societal trends of those decades. The students’ considerable reading and other research on the eras covered in the exhibit provided a solid historical context for their exploration of the Kane collection.

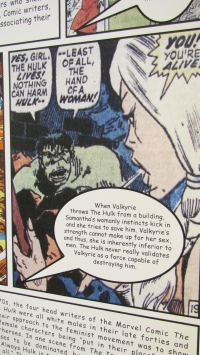

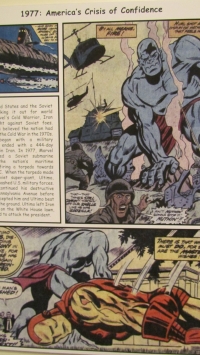

Among the students’ topics are the connection between the John F. Kennedy assassination and Captain America; Batwoman as “the perfect housewife”; Iron Man versus environmentalism; the transition from the Cold War to the anti-war movement in Marvel comics; and how superheroes’ myths – the supporting narrative that accounts for their individual strengths and weaknesses – have been recast in the wake of changing beliefs and attitudes. Students also lend analysis to a sometimes underappreciated but just as revealing aspect of comic books: their advertisements (“You can have a he-man voice!” “Own a real Texas ranch!”).

The Making History Public class is a collaboration between the History Department and University Libraries, which produced an exhibition last year on the history of the book based on the work of students of Professor Virginia Reinburg; an exhibition on Boston Common is being organized for the fall by students of Professor Marilynn Johnson. Faculty and library administrators say the History-Libraries partnership helps undergraduates gain valuable experience in planning, researching and organizing a research project, and learning how to utilize archival material.

“We want students to see Burns Library as a laboratory for the humanities,” says O’Neill Library Bibliographer/Reference Librarian Elliot Brandow. “Burns, like all BC’s libraries, is a tremendous resource, and students should know how to make use of it. They can learn the rules and guidelines for working in an archive: How to figure out what you’re looking for, to refine your search, to handle the materials. Like all scholars doing research projects, students have to draw upon time management and other organizational skills.”

“The task, essentially, is to give the students a tremendous amount of material, and the responsibility for making it understandable,” says Richardson, who was inspired to have the class work with Kane’s collection after Sundaram mentioned his donation. “What are the major themes and supporting ideas they want to put across, and how can they do this in a way that’s coherent and comprehensible for the public? This class did a phenomenal job in coming up with a concept and turning it into a creative, intelligent, stimulating and visually engaging exhibition.”

The student researchers, for their part, say the organizational phase of the project was sometimes daunting. “This was different than any history class I’ve ever taken, and I was a little overwhelmed at first,” says Remy Hassett, a senior from Atlanta. “The collection contained about 11,000 comic books, and I couldn’t imagine having to sort through all of them. It took some doing for us to sort out the different parts of the project: ‘This is what I’m doing,’ ‘No, I’m doing that.’”

Plymouth, Mass., senior Lindsay Crane says, “You had 15 different personalities coming together, which wasn’t easy, and it was hard to get the papers culled down. But Justine helped us find our way around Burns, and the feedback from everyone made a difference.”

Once the project was underway in earnest, and the students were able to focus on the subject matter, they found plenty of compelling storylines and snippets of American life.

Crane, for example, looked at the fitness movement of 1970s America. “There seemed to be a lot of anxiety and uncertainty in the US during that decade, and people perhaps felt the one thing they could exert control over was their bodies – so memberships for fitness centers soared, and recreational sports like tennis and jogging became very popular.

“You can see this interest in fitness show up in comic books like Batman: In earlier periods, he was strong but not very toned; then he got eight-pack abs and his body became sculpted, almost larger than life.”

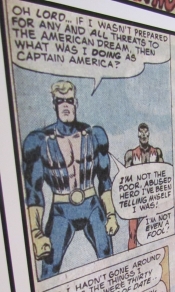

Mikayla Burke saw the pervasive grief and shock over the Kennedy assassination as a factor in Marvel’s 1964 reintroduction of Captain America, which had been discontinued a decade earlier. “Marvel wanted to create a patriotic, uplifting atmosphere, and Captain America embodied many great American ideals, including the notion that an average man could be come a hero.”

Captain America also was a barometer for Watergate-era America, according to Willem Van Geel: In one story arc that unfolded during the Nixon presidency’s final months, the star-spangled champion exposes and defeats a political conspiracy inside the White House that leaves him so disillusioned with the US government he abandons his super-hero identity.

Later, Van Geel notes, Cap has a change of heart “after he recognized the American people and their ideals were worth fighting for, even under a corrupt and crooked government. This individualistic patriotism mirrored a conservative voice in society that was growing louder and called for more individualism and a less important, less powerful government.”

Richardson lauds these and other findings that came out of the students’ research. “Because they didn’t live through the ’60s and ’70s, they saw things I didn’t see about the events and trends of the era. It’s great for teachers to learn from their students’ work, and I certainly did in this case.”

The illustrations on this page are photos of the exhibit “Revealing America’s History Through Comics, on display in the History Department, located on the third floor of Stokes Hall South.