By

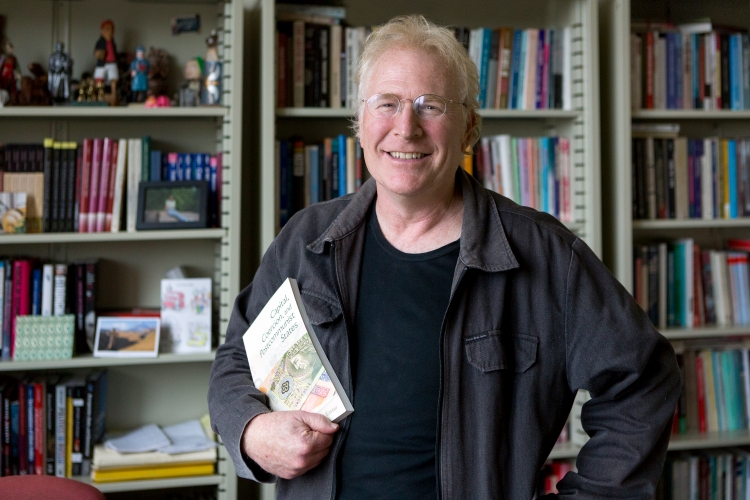

Professor of Political Science Gerald Easter has won two major awards from the Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies for his book, Capital, Coercion, and Postcommunist States, which examines divergent approaches to taxation among former East Bloc countries, and the subsequent political and economic impacts these had.

Easter’s book was selected for the Ed A. Hewett Book Prize, awarded for an outstanding publication on the political economy of the former Soviet Union and East Central Europe and their transitional successors. The book also earned the Davis Center Book Prize in Political and Social Studies as the best monograph on Russia, Eurasia, or Eastern Europe in anthropology, political science, sociology or geography.

“Winning a book award is nice, and winning two book awards is even nicer,” said Easter, who published Capital, Coercion, and Postcommunist States in late 2012. “I worked on the book for a long time, with no shortage of anxiety along the way, so that hopefully it will say something meaningful and might be enjoyable to read as well. Academic research is a rather solitary endeavor, and you never really know who, if anyone, is paying attention. I suppose, mostly, the book awards confirm that all the time, effort and fretting was worth it.”

Easter traces the inspiration for the book to a period in the 1990s when he lived in Russia – not long after the disintegration of the Soviet Union — and witnessed a fiscal crisis there that triggered bank runs and effectively wiped out people’s life savings.

“The government had been accessing capital through a pyramid scheme, issuing short term bonds at incredibly high rates of return — upwards to 100 and 150 percent — until it simply ran out of money to pay off. The government was forced into doing this because it could not, for administrative reasons, and would not—for political reasons — collect the taxes necessary to support its expenditures.”

Visiting Poland a year later, Easter saw a vastly different system for conducting state finances: “The Polish government succeeded in making new taxes, which people paid — maybe not fully, but enough so that the government was able to fund itself. So it made for a neat comparison: How two post-communist states, starting from similar places, ended up with very different tax systems, which in turn influenced the outcomes of their larger political and economic transition.”

As Easter explains in the book, the "contractual" state as exemplified by Poland and the countries of Eastern Europe moved toward democratic regimes, consensual relations with society, and clear boundaries between political power and economic wealth. The "predatory" state associated with the successors to the USSR developed authoritarian regimes, coercive relations with society, and poorly defined boundaries between the political and economic realms.

The outcomes in both cases were not pre-determined, Easter believes, but the weight of history has a strong influence on each country’s path of development.

“The one factor that stands out regarding the two cases is the role of the post-communist elites in each country. In Poland, a core section of elites from rival political parties were united in that they wanted Poland to be a democracy, to have capitalism, and to be in the European Union. At every turn when conflict could have derailed the transition away from democratic and market reforms, rival elite actors were capable of sitting down and reaching a compromise solution.

“Russian elites, by contrast, were incapable of this. Always for them it is a zero-sum game, all or nothing. And when they encountered a crisis, rather than finding compromise solutions they dug in and, as a result, their economy collapsed and their nascent democracy went up in flames.

“Here at the root of these elite inclinations maybe we can bring history back in. There was something inherent in the national identity to the Polish elite, most likely fostered by an understanding of Poland's tragic past, which contributed to these strategic compromises during the transition. Russian elites, by contrast, have always been and continue to be dependent on the state for their status and wealth. They compete among one another for political favor, and ultimately are incapable of putting aside personal reward and uniting for a greater good. That is a consistent theme in Russian history from medieval times to contemporary times.”

Capital, Coercion, and Postcommunist States is chronologically the last part of Easter’s trilogy on the communist state – although he hasn’t yet written the middle part. “My first book was a study of the building of the communist state, focusing on the Soviet Union with a case study of regional administration. The next monograph will be the fall of the communist state, and will include a wider country comparison — USSR, Poland, East Germany, Czechoslovakia, and Romania — with a case study of the role of coercion. It will focus specifically on the dramatic moments at the end of the old regime when protest movements challenged the authorities, which responded by sending out the police to put down the protests. It will seek to answer the question of why, at these critical junctures, did the state's coercive forces either obey or mutiny?”