By

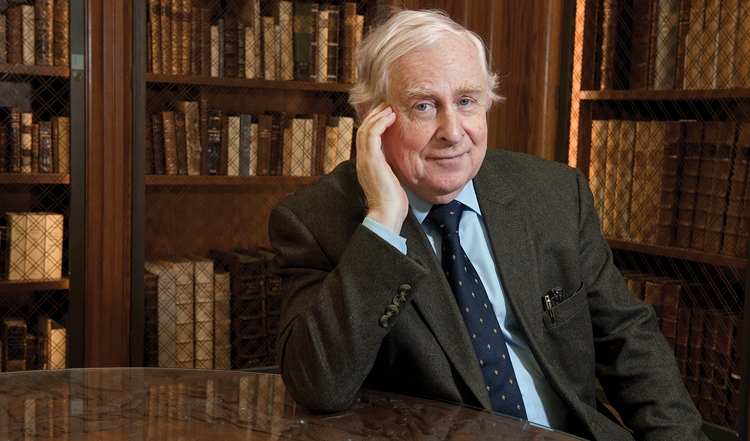

Being a scholar of 20th-century Irish history when personal papers and official state archives were nearly impossible to obtain in Ireland made Dermot Keogh appreciate “the value of good material.” So imagine his delight in being the Burns Visiting Scholar of Irish Studies at Boston College, and having a chance to peruse one of the world’s most acclaimed holdings of Irish history and culture.

“It’s second to none,” says Keogh of the University’s John J. Burns Library Irish Collection. “The library is simply exceptional from the point of view of a researcher, and Boston College itself is equally impressive in its energy, ethos and work ethic.”

Keogh, who is emeritus professor of history and Emeritus Jean Monnet Professor of European Integration Studies at University College, Cork, will offer a glimpse into his multifaceted scholarship on March 28 when he presents the lecture "Contrasting Studies of Irish Catholic Intellectuals in a Revolutionary Age, 1908-1919," at 4 p.m. in the Burns Library Thompson Room.

Some of Ireland’s most eminent experts in history, literature, bibliography, language and art have served as Burns Visiting Scholar in Irish Studies, and use the Burns Irish Collection for research. In addition to research obligations, the Burns Scholar teaches two courses and presents two lectures each academic year.

A Dublin native, Keogh has amassed numerous academic honors and achievements, including two Fulbright awards — one of which brought him to BC in 2002 — as well as fellowships at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington, DC, the Institute for Irish Studies, Queen’s University Belfast and the European University Institute in Italy. He is the author of nine monographs, has edited five books and co-edited 16 others, and written more than 50 book chapters and 40 scholarly articles.

But when he started out in the 1970s, says Keogh — who also worked as a broadcast and print journalist — being an Irish historian carried a certain occupational irony: If you wanted in-depth information on anything relating to Irish government and policy, you were better off doing your research somewhere other than in Ireland, because its official archives were largely inaccessible to the public.

“You would actually have more luck going to London, or Paris, or Rome, or Washington, DC, to find documents or papers that pertained to Ireland,” he says. “It could be a real challenge to find what you were looking for, so you appreciated the value of good material.”

The opening of Irish government archives in the late 1980s and establishment of the National Archives of Ireland has meant a wealth of new opportunities for scholars like Keogh, whose research has included topics like Jews in 20th-century Ireland, Ireland and European integration, and Ireland’s relationship with the Catholic Church.

“With more archival materials available, questions that earlier generations of historians might have wanted to ask can now be examined,” he says. “The historical narrative has expanded radically, to include areas of history — some of them contentious — that appeared to have been neglected previously. It’s possible now to write about the evolution of Irish institutions, especially state-funded institutions run by religious orders, in a more definitive way.

“But it’s very important that this generation of historians responds in an active way, and moves beyond any preconceptions and mindsets to produce work that broadens our understanding of Ireland’s social, religious, economic and political development.”

While Keogh — who is utilizing the Burns archive to help him expand on his previous book about Irish-Vatican relations, as well as write a manuscript on the Catholic Church and the origins of the Irish State, and aid his research on Irish-European integration — may have spent most of his professional life as an historian, he has found that a journalist-like doggedness and perseverance has served him well. “In the end, whatever research you’re doing, nothing replaces hard work. It’s all about dedication and commitment, to find your sources and develop them.”