By

Political evil is back.

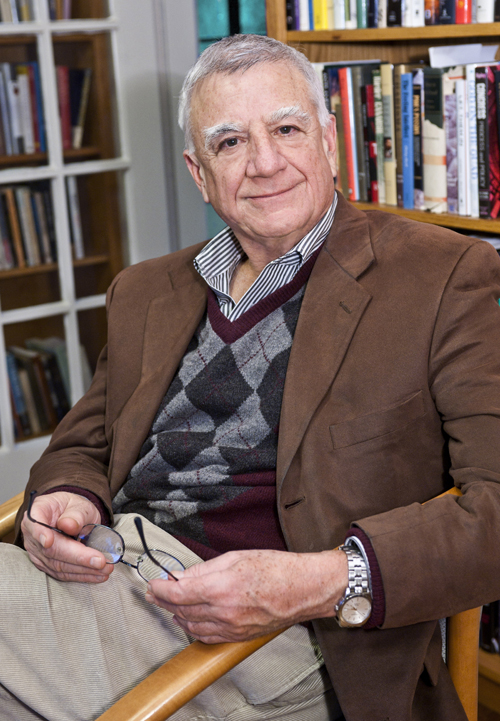

Or, more accurately, it never really went away, says Professor of Political Science Alan Wolfe, director of Boston College’s Center for Religion and American Public Life.

But two decades after post-Cold War optimism spurred talk about the end of ideology, and the ascendancy of secularism and liberal democracy, Wolfe says, it is all too apparent — from 9/11 to Rwanda to Darfur — that the world is beset by what he defines as political evil: “the willful, malevolent, and gratuitous death, destruction, and suffering inflicted upon innocent people by the leaders of movements and states in their strategic efforts to achieve realizable objectives.”

The nature of political evil, manifested through terrorism, ethnic cleansing, genocide and counter-evil — “the determination to inflict uncalled-for suffering on those presumed or known to have inflicted the same upon you” — is the subject of Wolfe’s newest book, Political Evil: What It Is and How to Combat It.

As Wolfe notes, political evil is not an unfamiliar, or particularly recent, entity: Thinkers like Hannah Arendt, Reinhold Niebuhr and George Orwell wrote about it, and millions fought against it in World War II. But over time, he says, an unfortunate mix of trends — domestic political gridlock, ideological splintering, breakdown in social civility, misreading historical lessons — have seemingly sapped the collective will or ability to effectively confront political evil.

Now, says Wolfe, it is time to “get serious” about understanding and combating the use of evil to achieve political ends.

“We were left with an impressive language and a great vocabulary from the era of totalitarianism [1930s and 40s] with which to talk about political evil,” says Wolfe. “The problem is too often we apply it incorrectly or inappropriately, such as comparing Obama or Bush to Hitler.

“But it goes beyond that: However monstrous their acts, Osama bin Laden or Slobodan Milosevic should not be given the ‘Hitler’ tag, either, nor should the civil war in Darfur — terrible as the events there may be — be described as an act of genocide. These may seem overly analytical distinctions, but you have to look carefully at the relationship between the perpetrators and the victims of political evil, and the unique characteristics of each act of political evil – the strategy, the methods, the purpose it served.

“If we don’t scrutinize political evil, then we don’t understand it, and if we don’t understand it, we can’t combat it.”

Darfur, the 1994 Rwandan genocide, Neville Chamberlain’s appeasement of Nazi Germany, ethnic cleansing in the Balkans, 9/11, and controversy over Israel’s security measures are among the events and situations Wolfe — drawing upon writings of Saint Augustine, Mani, Madison and Machiavelli, among others — assesses in explaining the nuances and dilemmas political evil can present.

Wolfe also explains how misinterpretations or mischaracterizations of politically evil acts can result in responses that are ineffectual, serve to worsen the situation, or create a new set of problems. He analyzes humanitarian organizations’ views on Darfur, for instance, the furor over Israel’s 2008 Gaza offensive, and the Bush Administration’s use of torture and rendition of terror suspects in the post-9/11 “War on Terror.”

In humanity’s attempt to grapple with political evil, Wolfe says, the pendulum swung too far from isolationism and pacifism to an “uncritical acceptance” of militarism. “Once we may have neglected evil, but now we became obsessed by it. We lacked the thing we needed most in dealing with political evil — perspective. It’s time to get the balance right.”

One recent development, which occurred after the book’s publication, suggests a means for dealing with political evil, says Wolfe: the ouster of Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi. Gaddafi’s four decades of despotism included a personal tragedy for Wolfe, whose cousin was killed in the 1988 Lockerbie bombing widely believed to have been ordered by Gaddafi. But even here, Wolfe says, perspective is necessary.

“There is no question in my mind that Gaddafi was an evil man. But to denounce him as the epitome of evil, or put him in the category of a Hitler or Stalin? No. I think Obama handled the situation very well. Although his criticism of Gaddafi was clear and unmistakable, he avoided black-and-white, demagogic language. He let the Libyans take the lead in the struggle, and while there are certainly questions surrounding the death of Gaddafi and whether he should’ve been brought to justice, this was a case where political evil was eradicated.

“Again, however, what worked in Libya — at least thus far — may not work elsewhere. We have to have a full understanding of the events in Libya, and why they unfolded as they did, to derive useful lessons from the experience.”