Eagle Intern Fellow Jaime Martinez ’20, on the east steps of the U.S. Capitol. (Image: Mark Finkenstaedt)

Forty-three percent of college internships nationwide today are unpaid, according to the National Association of Colleges and Employers. Many academically qualified Boston College students can’t afford to participate or need to take on paying jobs in addition to an internship. (To supplement an internship at Boston’s alt-weekly newspaper The Phoenix, I spent nights as Brighton’s least intimidating bouncer at Roggie’s, RIP.) In 2014, the Career Center launched a program to “remove financial barriers, so any student can explore any career” of personal interest says Joseph DuPont, associate vice president for student affairs/career services. Funded by the University and by gifts, the Eagle Intern Fellowship provides each recipient with a $3,500 stipend. Between 150 and 250 rising sophomores, juniors, and seniors apply every year. Of this year’s 71 Eagle Fellows, 21 percent are first-generation college students and 39 percent are AHANA (African-American, Hispanic, Asian, or Native American).

Recipients pair with “career coaches” from among the center’s staff of 17, and share reflections on their work over Skype at the beginning, middle, and end of their internships. In September, they participate in a public poster session.

This year’s awardees, who during the school year study within 26 of the University’s majors, have been working during the summer in 12 states and 10 countries, in venues ranging from a veterinary clinic in Watertown to the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in Jordan, the Eradicate Childhood Obesity Foundation in Cambridge, and the Museo de Arte Moderno in Buenos Aires. In June and July, BCM visited Eagle Fellows at work in Boston, New York, Washington, D.C., Houston, and Cape Town, South Africa.

Karissa Mokoban ’20

John W. McCormack Building, 19th floor

Boston, Massachusetts

Mokoban (right) outside the attorney general’s office with Madeline Raster, an intern from Harvard. (Image: Lee Pellegrini)

Because Karissa Mokoban spends most of her day analyzing and cataloging classified documents pertaining to ongoing criminal investigations, the office of Massachusetts attorney general Maura Healey denied BCM’s request to play fly on the wall while Mokoban worked. “Karissa handles extremely sensitive and confidential material,” said administrative assistant Marsha Cohen, Mokoban’s supervisor. Instead, I’m asked to pass through security in the lobby and take the elevator to the criminal bureau on the 19th floor, where a receptionist, behind bulletproof glass, unlocks the entrance and leads me to a small conference room veiled by frosted glass. Mokoban sits upright in a Kelly green blazer over a black dress. Cohen and deputy press secretary Chloe Gotsis sit nearby to monitor the discussion. “I’ll try to walk you through my day without leaking anything,” Mokoban says, laughing.

On Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Fridays, she enters her cubicle down the hall from the conference room at 9:00 and checks her email, reading briefings about the latest investigations. Among dozens of other cases this summer, the office has sued the giant opioid maker Purdue Pharma for misleading doctors about the dangers of OxyContin and the Environmental Protection Agency for illegally rolling back climate protection regulations, and is leading an 11-state investigation into a “no-poach” agreement by eight fast-food companies that prevents employees from switching franchises. “A lot of this summer is about learning how many different ways people try to commit crimes,” says the sociology major.

Then she’ll set to work on her latest project. As cases develop, attorneys from across the criminal bureau email her case files and visit her desk to explain the investigation. “By the time I’m on a project, I know how it will connect with the investigation as a whole.” So far she’s worked with the state police and the divisions of human trafficking, of enterprise, major, and cyber crimes, and of financial investigations. “It turns out everything isn’t resolved by the end of the [television] episode,” she says. In July, Mokoban spent about 40 percent of her time on spreadsheets, logging bank statements, time sheets, and other financial data. “My Excel skills have grown exponentially,” she says. “But I know now that I don’t want to work with numbers all day.” She also transcribes witness interviews—”that’s when I’m most alert, and I feel the empathy building in me”—and analyzes and documents surveillance footage, second by second. Every two weeks, she also runs the reception desk, fielding calls from citizens filing criminal complaints.

In a 19th-floor conference room with Raster and intern Danielle Miles-Langaigne from the University of Pennsylvania. (Image: Lee Pellegrini)

Mokoban, who was raised by her Haitian immigrant parents in Vero Beach, Florida, is considering joint advanced degree programs in law and public health, but she is still exploring potential careers. “I applied to this office because I wanted exposure to a lot of sectors,” she says. “And Maura Healey, being the first openly gay attorney general in the United States, and having the mentality of helping people that I have, definitely spoke to me.”

A few times a week, Mokoban researches staff in the Attorney General’s healthcare division one floor below, and then emails them asking to learn more about their work. She also attends the office’s many programs for its 40 undergraduate interns, which include training sessions for deposition taking, writing motions, and investigating cybercrimes. The interns also attend trials, “meet-the-attorneys” networking events, and moot court sessions. “Wow do they give harsh, blunt, but very constructive feedback,” Mokoban says. “I’m searching for a word that’s more sophisticated than ‘chill,’ but everyone here is level-headed,” she says. “They’re wrestling with intense investigations, but it’s reassuring that they don’t let that stop them from living normal lives.”

After exactly 45 minutes, the press secretary ends the interview. Mokoban has just received a new, classified assignment and deadline.

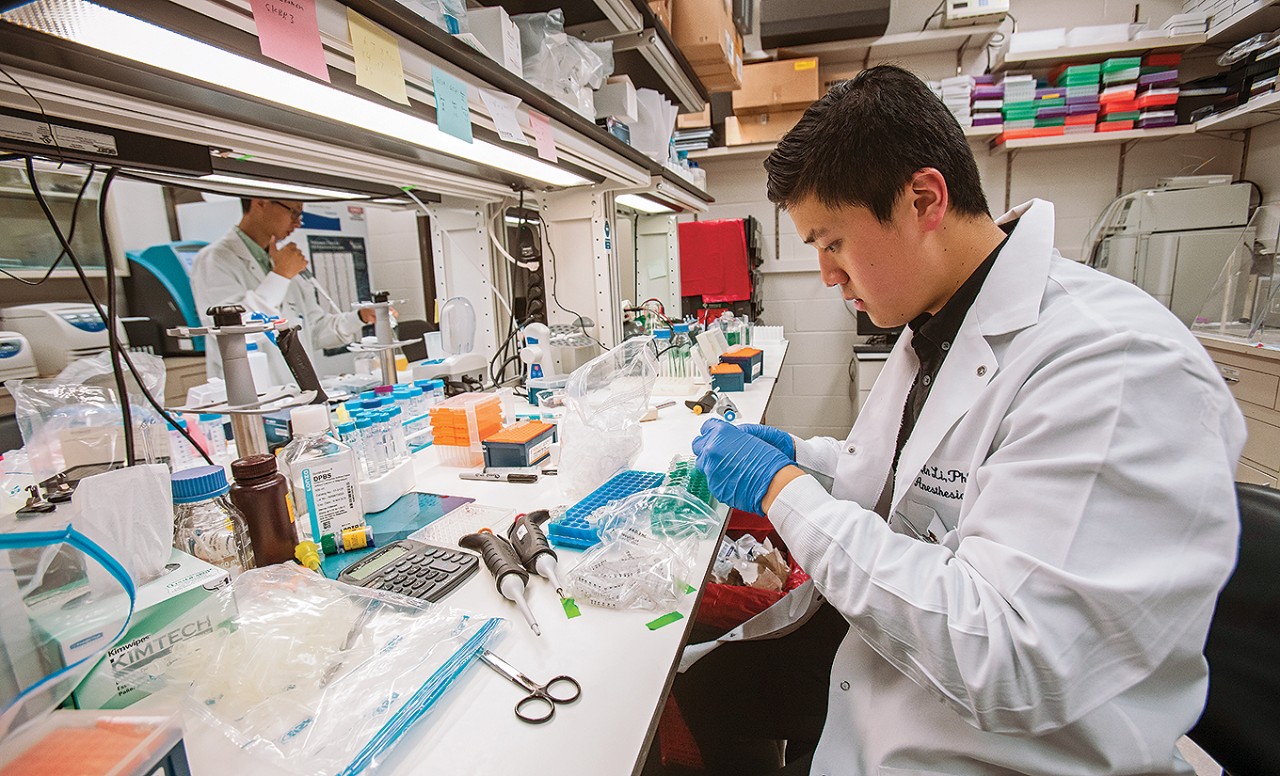

Matthew Yan ’21

University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, sixth floor, Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine Lab, Houston, Texas

Yan pipettes purified jellyfish protein samples into test tubes. Post-doc Zhang can be seen at left. (Image: Daniel Kramer)

Alone in a compact lab with warbling centrifuges, spinning trays of test tubes, rows of micropipettes marked with all-caps radioactive signs, and a microwave—”Don’t know what that’s for yet, but it’s not for lunch,” he says—Matt Yan pulls a beaker containing 300 millileters of a fizzy, lemonade-colored solution from a refrigerator. He’s spent two weeks cultivating and diluting the mixture—a saline broth of isopropyl-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside, which triggers protein expression, and E. coli cells carrying GFP, a bright green florescent protein found in jellyfish and used as a marker in cellular biology. With slicked black hair and wearing a black button-up, black track pants, blue plastic gloves, and an oversized white lab coat with the name of a former post-doctoral fellow stitched over the breast pocket, Yan carries the beaker across the hall into a room filled with large freezers belonging to labs in MD Anderson’s Center for Neuroscience and Pain Research. He places the beaker in an incubator shaker, which resembles a microwave. He sets the machine to 2.8 degrees Celsius (37 degrees Fahrenheit), and sets his iPhone alarm for four hours later. At that point, the protein may or may not be pure, and he may or may not be one step closer to answering the main question to which he’s devoting his summer in Texas: Do isotopes Carbon-12 and Carbon-13 affect the florescence of GFP differently? The answer may open up another avenue of testing. “It’s exhausting. Hard work is hard. I’m finally seeing the struggle of being an adult,” says the 18-year-old Yan.

The biochemistry major spent much of his freshman winter break at home in San Francisco researching labs across the country and emailing principal investigators he wanted to work with. The lab of Jiusheng Yan (no relation) investigates the structure, function, and regulation of ion channels related to pain, “something we all experience every day but most of us know nothing about.”

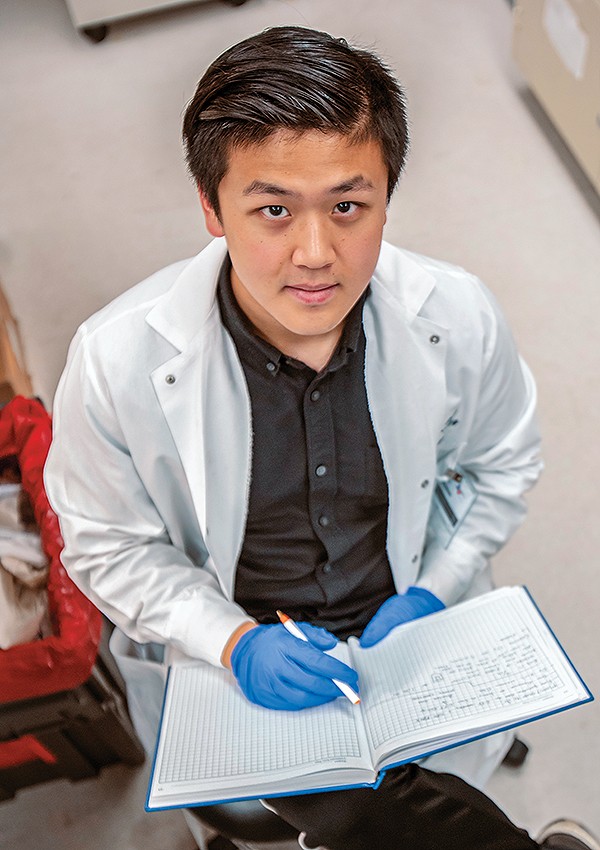

Yan with his lab notebook. (Image: Daniel Kramer)

As the lab’s only intern, Yan enjoys a one-on-one apprenticeship with Jiyuan Zhang, the lab’s soft-spoken, meticulous, postdoctoral fellow. Zhang has worked at the lab since 2013 and ceaselessly pivots around the lab like a fly on a mission. Before Yan runs any experiment, Zhang spends hours demonstrating each step—how to manipulate a rotovapor, how to analyze CRISPR, how to measure mass spectronomy. “You can train a monkey to run a Western blot [a process using antibodies to detect proteins],” Zhang has said to Yan, but “scientists have true understanding of why we use each technique.” “The greatest luxury is having the time to constantly ask why,” Yan adds. “Why pour this quantity of LB broth? Why is calcium signaling important to pain medicine?”

Once he’s learned a method, Yan is often free to experiment unsupervised. At Friday afternoon lab meetings, he shares his findings from the week and his goals for the next week via PowerPoint, receiving feedback from Xin Guan, the lab’s other post-doc, and the principal investigator. “I’ve learned to present data so much more effectively.”

“The amount of waiting time in a lab surprised me the most,” he says midway through his 12-week stint in Houston. While his bacteria grows or his protein activates, Yan watches Zhang conduct his own experiments, reads recent papers on pain medicine research, and grabs Chick-fil-A in the cafeteria. A few times a week, he takes a shuttle bus to the South Campus—MD Anderson spans eight million square feet of labyrinthine buildings over 63 acres—and shadows his older sister, a graduate research assistant for a laboratory that develops gene therapies to treat brain cancer.

At 2:30 p.m., Yan pulls his solution from the incubator and finds that the protein is riddled with contaminants; the experiment is a bust. “It’s humbling to fail almost every day,” he says, laughing. “I’m learning that you have to be willing to devote years to a project that may amount to nothing. But science is failure.” The next day, Zhang will teach Yan how to purify the protein by hand.

Jaime Martinez ’20

Cannon House Office Building, Room 437, Washington, D.C.

Martinez (right), with press aide Benjamin Cole, in Congressman Vela’s office. (Image: Mark Finkenstaedt)

Jaime Martinez sits at the back of a compact, high-ceilinged, wood-paneled office that houses 11 others—on the phone, marking up documents, or typing at their desks—on June 26. Beneath three-foot-tall portraits of a white-tailed deer, a desert cardinal, a Gulf squareback crab, and other flora and fauna of Texas’s 34th district, which borders Mexico, he is hunched over a laptop in a simple wood chair. In the three weeks since the rising junior political science major began interning for Democratic U.S. Representative Filemón Vela Jr., he’s been fielding up to 10 phone calls a day from constituents concerned about the Trump Administration’s family separation immigration policy (which was suspended on June 20). His task this morning is to create a sheet of bullet points comparing the number of children who remain apart from their families as reported by CNN, MSNBC, Fox News, CBS, and other networks. Vela will cite the variance among these statistics in interviews with the media and when debating on the House floor.

Growing up in Mexico City, Martinez was “fascinated by the way American politicians used their intellect and their personality to try to change history.” He immigrated with his family to the border town of Brownsville (within the 34th district) when he was 15, and saw Vela speak at his high school. Last winter, he called the same constituent hotline he now answers and inquired about an internship. “I didn’t want to just apply online. I wanted to apply to a person.”

Martinez spends his 8:30 to 5:30 workdays in this bustling office on Independence Avenue. He conducts research on pending bills; translates constituents’ letters and social media posts from Spanish to English; stocks office supplies; ships surplus books from the Library of Congress to underserved schools in the 34th; attends and writes briefings on caucus meetings and special interest lectures (topics have ranged from human trafficking to Canadian tariffs on American lumber); and pinballs across the cavernous, marble-floored Cannon Building to pop into its many 10-foot-high doors and ask other U.S. Representatives to sign various petitions his Congressman authors (e.g., to convince the president to declare a state of emergency, from flooding, in the Rio Grande Valley). Once a week Martinez gives visiting Texans up-to-two-hour tours of the U.S. Capitol. “It slows down a lot when Congress isn’t in session. That’s when you struggle to prove yourself,” says Martinez. “You want to keep asking, What can I do? But you don’t want to constantly disrupt. That’s a useful skill I’m learning: keeping busy even when it’s not busy.”

In a fourth-floor Cannon corridor. (Image: Mark Finkenstaed)t

At 10:15, an electronic bell warns, from the 15-foot ceiling, of a pending vote on the House floor (on the Endangered Salmon and Fisheries Predation Prevention Act), and Vela darts out of his open office next door. “Watching him from up close,” says Martinez, “I see how sleep-deprived he is travelling back and forth from the district, how many meetings and endless follow-ups there are to introducing and writing and passing every bill, the tirelessness and conscientiousness it takes to represent your people.”

The bell was also Martinez’s cue to head to a conversation on “Free Markets, Individual Liberty, and Civil Society,” between U.S. Senators Rand Paul (R–Kentucky) and Mike Lee (R–Utah). Martinez signs up for several congressional lectures a week, often given by members on the other side of the aisle. “I’m trying to absorb as many perspectives here as possible.” Over the hour-long dialogue, Martinez fills eight pages in his black congressional notepad, underlining a note to read Federalist Paper 51 that night. Walking back from the Russell Senate Building, he pauses outside the Supreme Court to watch hundreds chant “Keep families together,” in protest of the Trump v. Hawaii decision moments earlier to uphold a travel ban.

After a quick lunch in the basement cafeteria, Martinez watches a few minutes of the Australia-Peru World Cup soccer match at the press assistant’s desk. He sorts through the day’s foot-thick bundle of mail (which has been screened for poison), and throws away an issue of Hustler. “The publisher [Larry Flynt] has mailed every issue to every member of Congress since the 1980s,” says the press assistant. The office’s legislative director, Julie Merberg, asks Martinez to file a brief on the top five reasons citizens of Central America’s Northern Triangle—El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras—are migrating to the United States.

“On days with nonstop action, I get very excited to come back here after I graduate,” says Martinez.

Tia Rashke ’19

Southern African Bishops’ Conference Parliamentary Liaison Office, Cape Town

Tia Rashke '19 working with administrator Robyn-Leigh Adonis, in the liaison office. (Story by Christopher Clark; Image: DNA Photographers)

Almost 25 years since the dawn of democracy in South Africa, Cape Town remains one of the most segregated cities in a country of stark inequality. As property prices skyrocket in a cosmopolitan and rapidly gentrifying city center, the city’s black South African population continues to be routinely relegated to the impoverished peripheries. Over the past six months, beginning in February, Tia Rashke, a theology major from Madison, Wisconsin, has had a chance to view the city close-up, first as a student for a semester at the University of Cape Town, and this summer as an intern with the Southern African Bishops’ Conference Parliamentary Liaison Office, located near South Africa’s parliament buildings and within sight and sound of regular protests that speak to the persisting injustices of post-apartheid South Africa.

Rashke arrived in Cape Town toward the end of a prolonged drought that threatened to run municipal taps dry. But the winter has been unusually wet, bringing relief, and on a July day it’s raining as Rashke works in an office stocked with shelves of bound reports on the nation’s history and social issues, car tires hissing on the nearby street. She is just more than half way through her two-month internship at the bishops’ liaison office, where her primary project has been researching and writing a briefing paper on how migrant children are received around the world.

Rashke, near Cape Town’s St. Mary’s Cathedral. (Image: DNA Photographers)

Her interest in the subject was piqued by news coverage of the separation of children from their parents at the U.S.–Mexico border. But her project coordinator, Mike Pothier, encouraged her to take a “global approach” to an issue that also has relevance in South Africa, a country whose relationship with its sizeable immigrant population is often fraught.

During her semester at Cape Town, where she took courses in “Religion and Politics,” “Crime and Deviance in South African Society,” and “Political Philosophy,” Rashke became involved with the university’s Catholic Students Society, which holds regular church services and social gatherings at its on-campus hub. It was one of the society’s in-house priests who encouraged Rashke to apply for an internship at the liaison office. “I wanted to extend my time in Cape Town as much as possible to integrate myself and learn as much as I could,” Rashke says. Once the college semester was over, she moved from an apartment near campus, on the outskirts of the city, to a loft apartment downtown that’s within a few minutes’ walk of the liaison office.

As well as submitting briefing papers for presentation to parliament, the bishops’ liaison office organizes roundtable events to discuss pressing social issues with relevant NGOs and stakeholders, church leaders, and members of parliament. Through her internship, Rashke has helped to organize some of these events and is writing a briefing paper on detainees awaiting trial that will serve as the basis for the office’s next roundtable meeting.

Rashke, who chose Cape Town for her junior year abroad because she felt it had “more to offer in terms of different experiences and cultures than a university in Europe,” says the added internship has helped to give her a sense of Cape Town that goes beyond what many short-term visitors are able to obtain. This is largely thanks to the formal discussions she’s been privy to at work and to the willingness of her diverse South African colleagues to share their own personal experiences. Ultimately, Rashke says, she’s come to see Cape Town as a “complicated place,” with so much beauty and so much injustice side by side. “I haven’t yet figured out how to articulate my enjoyment [of the city] alongside the struggles that you see,” she adds. Rashke believes that her biggest challenge has been “trying to figure out what I can contribute as a white American who’s here only for a short period of time,” but says that she has begun to grow “more comfortable” with the fact that there “aren’t all that many easy answers.” At a practical level, she says, her internship has given her more workplace independence than she’s used to, which she’s found “a little disorientating at times but also exciting.” Ultimately, Rashke says, the internship “has confirmed my desire to be part of an environment that’s either related to or within the Catholic Church, and that [faith] doesn’t have to be separate from your work.”

Daniel Schantz ’20

104 West 29th Street, 11th floor, New York, New York

Schantz (center) with other Relix interns. Their supervisor is at far left. (Image: Gary Wayne Gilbert)

In a plain black T-shirt, white Bermuda shorts, and running sneakers, Daniel Schantz, who goes by Danny, is among the more formally dressed at Relix Magazine‘s headquarters in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood. The red-and-white walls are crowded with oversized prints of magazine covers; psychedelic posters of the Grateful Dead, Phish, and Cream, some of which are signed; white string lights; and a three-foot-tall orange foam finger with “Fans.com” printed on the palm. Nineteen-seventies reggae plays on surround-sound speakers and Schantz, who is developing a spreadsheet of summer and fall holidays that may be ripe for magazine promotions, swivels in rhythm in his chair at one end of a conference room table he shares with seven other student interns. “Oh word,” he calls out. “We’ve got so many Deadheads among our subscribers. What about August 21, Senior Citizens Day?”

“That’s brilliant,” says Harrison Ezratty, the magazine’s marketing coordinator and Schantz’s 24-year-old supervisor, positioned two feet behind Schantz at a desk in the corner.

Relix was founded in 1974 as a handwritten, photocopied newsletter informing Grateful Dead fans of amateur concert recordings, or “relics,” as the magazine’s founder called them. It’s evolved into an eight-times-a-year glossy (circulation: 100,000) dedicated to live music of all genres, with a heavy emphasis on jam bands. Schantz, an English major who minors in marketing and philosophy, grew up in New Jersey listening to “all hip-hop all day,” until his high school baseball coach played the Grateful Dead one day after practice. “It was thrilling. I didn’t know musicians could communicate with each other on that level.” Last winter he cold-called Relix, which he has been reading avidly for years, and inquired about an internship. “I love music more than anything. But you hear horror stories about the industry. I wanted to have an inside look before making it a career.”

In the archives with Isabella Fertel, an intern from the University of Pennsylvania. (Image: Gary Wayne Gilbert)

So far, Relix has only strengthened Schantz’s desire to get into the business. Two weeks earlier, eight staff members and nine interns drove in vans to the four-day Bonnaroo music festival in Manchester, Tennessee, and camped together in tents. Each day Schantz worked three four-hour shifts selling subscriptions to some of the 80,000 festival-goers from a booth (and saw 17 concerts in between). Initially “very timid about trying to sell a print magazine,” he learned from watching Ezratty and a sales executive that “people want to be sold. You just have to come to them and engage them first.” By the festival’s last day, says Schantz, “I called out anyone I saw wearing tie-dye. ‘Nice shirt. You like the Dead? Well, have you heard of Relix?'”

When he’s not working at a festival or concert in Brooklyn or Manhattan (about twice a week), Schantz commutes by train from his childhood home in Hillsborough, New Jersey, to the Relix office. He packages posters, T-shirts, and back issues; removes out-of-stock items from the website; helps manage the magazine’s email list; researches potential marketing promotions; and listens to new acts (“screening to see if they have that jammy Relix sound”) before calling their managers about partnering with the magazine. “I’m in the business of making the staff’s lives easier,” he says. The magazine has a full-time staff of 17.

At 2:30, Relix‘s bearded, Hawaiian-shirt-clad video coordinator calls out to Schantz from across the room. “Want to sound manage for the band?” Each week, the magazine streams a live performance of a visiting artist, à la NPR’s Tiny Desk Concert series.

The spindly, six-foot-four Schantz steps into the office’s cramped, black-walled recording studio, dons ear-engulfing headphones, and begins counting down for the Mike Montrey Band, a folk quartet. Over their three-song set, his eyes focus on the soundboard, dialing down the mic here, turning up the bass’s gain there. When they finish, Schantz exclaims, “That was tight!,” shakes hands with the musicians, and heads back to his spreadsheet.