Students being tested for COVID-19 before the Thanksgiving break. (Lee Pellegrini)

In two-and-a-half weeks, on December 21, final exams will conclude, residence halls will close, and the 2020 fall semester at Boston College will officially be over.

The semester began on August 31 amidst concern and uncertainty over the COVID-19 pandemic, and its potential impact on the health and well-being of BC faculty, students, and staff, as well as on academic, administrative, and service operations. Five months earlier, the coronavirus had forced the University to suspend in-person classes for most of the spring semester.

But broad-based planning and preparations during the summer enabled the University to resume operations for the fall while protecting the health of the BC community. Face masks were required in classrooms and common areas throughout campus, which were reorganized as necessary to ensure social distancing. Faculty taught classes in a mix of in-person, online, and hybrid modes. Dining halls redesigned their layouts and provided additional grab-and-go items. An on-campus COVID-19 testing program for students and employees was introduced.

And life at BC went on. Not without some anxiety and trepidation: The University recorded a spike in the number of positive tests (73) during the week of September 7-13; another uptick occurred before Thanksgiving break, with 67 positives reported during November 16-22, out of a total of 11,225 tests conducted. But these proved to be outliers: As of Monday, the University had conducted 118,118 tests of BC community members since August 16 with a total of 418 positive cases (including 87,422 undergraduate tests with 397 positives); the University’s cumulative positivity rate stood at 0.353 percent.

While all members of the University community contributed simply by wearing masks, washing hands regularly, and social distancing, the work of Facilities Services, Dining Services, Health Services, and Residential Life was crucial to carrying out BC’s COVID-19 plans and protocols. These employees had to adapt to changes in some of the most basic aspects of their jobs, whether cleaning and sanitizing campus buildings, preparing and dispensing food, providing health care, or helping students maintain a positive campus living environment. These efforts to keep COVID at bay required continual communication and coordination among their respective departments, and with others throughout the University.

“Everything big we asked for, we got—the University really came through,” said Associate Vice President for Facilities Services Robert Avalle. “The rapport we built with departments and offices in academic, administrative, student affairs, and other areas—Dining Services, Health Services, ResLife—was so critical. It gave us all a rhythm to work with going into the semester.”

“The partnerships have been amazing,” agreed Associate Vice President for Residential Life and Special Projects George Arey. “Facilities, Health Services, Dining Services, Athletics, BC Police—they’ve all been incredibly helpful across the board, and we’ve enjoyed great communication. We’re hopeful the work we’ve done together this semester will put us in good stead for the spring semester.”

The University Health Services testing team has been conducting 8,000 to 9,000 tests per week among students, faculty, and staff. ( Lee Pellegrini)

At the epicenter of the University’s COVID-19 testing and contact tracing programs is Dr. Douglas Comeau, director of University Health Services (UHS) and Primary Care Sports Medicine, and his staff. Following the early September spike in coronavirus cases, BC significantly augmented its weekly testing, with an increased focus on infection trends on- and off-campus, as well as individuals identified through tracing, according to Comeau.

The UHS testing team involves a combination of UHS employees, per diem nurses, and athletic trainers, working Monday through Thursday from 8 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. They have been conducting 8,000 to 9,000 tests per week among students, faculty, and staff, on average, with results reported in between four to 26 hours. Rather than using an observed swab—self-collected by the patient under the observation of a medical professional—BC utilizes the CDC-recommended nasal swabbing test, which Comeau characterizes as the “better way” to assess whether an individual is COVID-19 infected.

Health care professionals and individuals trained through a Johns Hopkins-developed program serve as BC’s contact tracers. When BC experienced the rise in positive tests in early September, UHS was able to identify and test individuals with whom those testing positive had interacted; most tested positive.

“Our aggressive contact tracing protocols identified individuals who were affected and enabled us to quickly isolate them, which effectively resulted in a downward trend,” said Comeau. “Given our rapid response and teamwork, we’re operating at a faster pace than other colleges and universities in Greater Boston.”

UHS has continued to conduct symptomatic and asymptomatic testing for all members of the BC community, with symptomatic and asymptomatic tests conducted at a BC microbiology lab and other asymptomatic tests through the Broad Institute, Comeau explained. Students living on and off campus who test positive are immediately isolated for 10 days at Pine Manor College and Hotel Boston, where they are assisted by UHS and Residential Life staff.

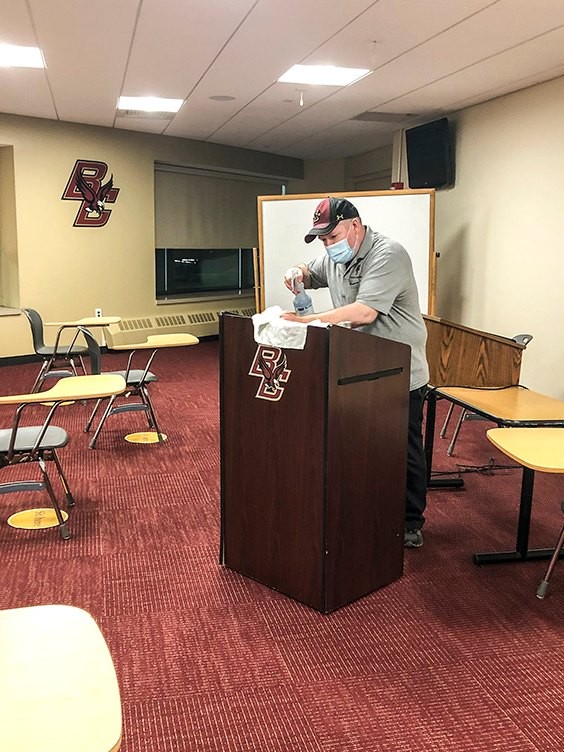

BC Facilities staff worked all hours to keep high-traffic areas sanitized.

Comeau and his UHS colleagues also have shared their expertise to help offices and departments formulate and implement safety measures. That includes Facilities Services, which in addition to applying its own intradepartmental protocols has carried out University-wide projects, such as reconfiguring classrooms to promote social distancing—right down to the “Don’t sit here” notices on some seats—constructing plexiglass barriers in customer service areas, and installing hand sanitizer dispensers in various parts of campus. Other tasks were less visible but no less important, like modifying the HVAC infrastructure of campus buildings to increase the circulation of fresh air.

Facilities Services’ ongoing, and most formidable, charge was to thoroughly clean and sanitize classrooms, residence halls, and other high-traffic, high-use areas of campus. A key asset was the department’s custodial/housekeeping third shift: about 75 staff members cleaning and disinfecting almost 30 buildings a night, including the University libraries, Connell Recreation Center, athletic facilities, academic areas, and science buildings—more than 200 rooms/areas in all, ranging from classrooms and auditoriums to bathrooms to elevators.

Cleaning and sanitizing residence halls multiple times a day necessitated some changes in routine for housekeepers and custodians, given that more students were likely to stay in the buildings than in pre-pandemic days. Staff had to clean lounges first—since students would typically use them throughout the day to participate in virtual classes—or start out on bathrooms and showers early in the shift. Students staying put in the residence halls also meant a higher volume of trash to be collected. Some additional custodial and housekeeping staff were assigned to residential areas to ensure the cleaning/sanitizing schedules stayed on track.

“ The rapport we built with departments and offices in academic, administrative, student affairs, and other areas was so critical. It gave us all a rhythm to work with going into the semester. ”

For BC Dining Services Director Beth Emery and her staff, dealing with the pandemic has been “like starting a new restaurant. It’s been a radical change. We had to reinvent how we serve students, our menu, and all of the safety precautions.”

The heightened safety and sanitation measures—employees required to wash hands every 30 minutes; dining halls closed between meal periods to sanitize all tables using an electrostatic gun; customers mandated to use hand sanitizer before entering serving areas—also meant reconfiguring dining halls for social distancing and to expedite the flow of traffic. BCDS changed its menus to focus on quick-serve meals and self-service options such as salad bars were removed in favor of grab-and-go items.

Even with masks and plexiglass shields, BC Dining staff have found ways to connect with students.

While the pandemic has limited interaction between dining staff and students, said Emery—something many BCDS employees miss—it has prompted expansion and creativity in other respects. BCDS has increased the capacity of orders and menu options that can be placed using the GET mobile application. More students are ordering their meals ahead of time, sometimes up to seven days in advance. At Hillside Café, students can pick up mobile orders in newly installed lockers; a QR code on their phone enables them to open the locker. The weekly farmers market, which offers local produce as well as breads and cheeses, has expanded operational hours and remained open later into the semester this year due to increased demand.

And even with masks and plexiglass shields, Emery notes, staff have found ways to give that personal touch, such as by placing stickers with inspirational quotes on cups and to-go containers.

“It’s all about student satisfaction and trying to do everything we can while considering the challenges of the pandemic and all of the restrictions that the board of health and the state require of us,” said Emery. “We constantly ask, ‘How can we make this the best possible experience for the customers?’”

The in-depth orientation on COVID safety the ResLife staff undertook during the summer prepared them for a big test even before the semester actually began: supervising the move-in of undergraduates to campus. What is normally a boisterous, often hectic (if generally good-spirited) event became far more orderly and regimented—“and de-densified,” said Arey. Students signed up in advance for a 60-minute block in which they were given an on-site COVID test and then moved into their residence hall, where they had to quarantine until their test results were complete; they were provided 24 hours’ worth of meals.

An even bigger challenge for the ResLife staff was to uphold their mission of fostering community and fellowship among the approximately 7,400 students living on campus, said Arey.

“We had to adjust our programming, obviously: We couldn’t do the usual kind of big-group, in-person activities. It was incumbent upon our resident directors, resident assistants, and graduate assistants to be creative and find ways to connect with students, check in with them and see how they were doing.”

Given the pervasive anxiety about COVID, Arey said, ResLife also sought to anticipate as many questions and concerns staff might encounter (“What if my roommate tests positive?”).

“The resident directors were exemplary in keeping the RAs and GAs upbeat and focused, and that positive nature has really helped the staff.”

When students were found to have tested positive, ResLife staff had to provide empathy and reassurance while also helping to begin the quarantine/isolation process, a particularly compelling instance of interdepartmental collaboration. In this, according to Arey, UHS was indispensable, as was the BC Police Department, whose staff transported students to and from quarantine/isolation housing. The Dining Services catering staff prepared and delivered meals for quarantined students, a job that entailed many last-minute requests and required flexibility. Facilities Services picked up and delivered laundry for students quarantining in their rooms.

Even as the semester concludes, these and other departments are looking ahead to the next one and the demands that it will bring—Facilities Services, for example, is readying for a busy athletics maintenance schedule and the planning and preparation for summer capital construction.

“In ResLife, we’ll be assessing what worked and what didn’t, doing a full review of our protocols, and looking to communicate adjustments in early January,” said Arey. “But we also feel it necessary to shut down for a bit, so our staff can relax and decompress. It’s been a non-stop semester.”

University Communications | December 2020