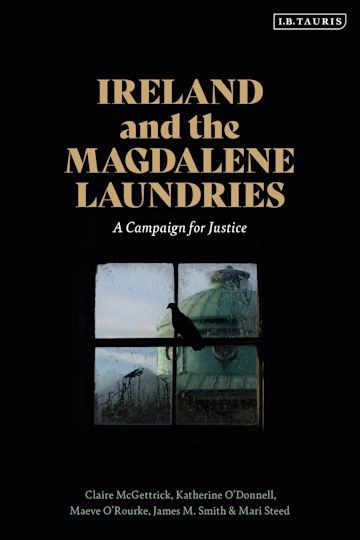

The Good Shepherd Laundry at Sundays Well, Cork, Ireland. (Photo by Fiona Ward)

Between 1922 and 1996, over 10,000 Irish girls and women, specifically unmarried mothers, and those considered promiscuous, sexually abused, and/or a burden to their families or the state, were imprisoned and subjected to forced labor in Ireland’s Magdalene Laundries.

Originating in Ireland in the 18th century, and operated by female religious organizations with government consent from the mid-19th century onwards, the secretive, commercial laundry facilities, named for the reformed Biblical sinner, Mary Magdalene, were a generally accepted social institution in the absence of an effective social welfare system.

Though originally devised as places of refuge, the Laundries’ initial objective to “protect, reform, and rehabilitate” devolved to a regimen of cruel, psychological, and physical maltreatment of the incarcerated women and young girls. By the early 20th century, the Laundries were a means to preserve the patriarchal-driven social order, and were propelled by Ireland’s historically conservative sexual values.

James Smith (Photo by Lee Pellegrini)

Shrouded in secrecy, the abusive system went largely unchallenged until 1992 when the Sisters of Our Lady of Charity decided to pay its debts by selling some of its land at their High Park, Drumcondra convent, and properly petitioned Dublin officials to exhume, cremate, and re-inter the bodies of 133 former Magdalene women buried there. But the exhumation unearthed an additional 22 human remains, scores of the women were unrecorded, and many more had missing death certificates, while others were mis-identified on headstones subsequently erected at Dublin’s Glasnevin Cemetery. A startled community demanded an investigation, transforming an open secret to front-page news.

Utilizing the Irish government’s 2013 inquiry, as well as state records and survivors’ witness testimonies, a new book, Ireland and the Magdalene Laundries: A campaign for justice, not only provides a detailed account of life behind the asylums’ secluded walls since the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922, but explores academic and survivor activism; the Irish government’s evasive response to the Inter-Departmental Committee investigation (also known as the McAleese report), and the formation of the volunteer-driven survivor advocacy group, Justice for Magdalenes (JFM), which continues to fight for restorative justice today.

The volume is co-authored by James M. Smith, an associate professor in BC’s English Department and the Irish Studies Program, and author of the 2007 book Ireland’s Magdalen Laundries and the Nation's Architecture of Containment.

Smith’s collaborators include Claire McGettrick, an Irish Research Council scholar at the School of Sociology at University College Dublin (UCD); Katherine O’Donnell, M.A. '91, an associate professor, UCD School of Philosophy; Maeve O’Rourke, a lecturer in law at the Irish Centre for Human Rights, National University of Ireland, Galway; and Mari Steed, born in the Bessborough Mother and Baby Home in County Cork, whose mother lived in a Magdalen Laundry, and one of more than 2,000 children exported—at age two—from Ireland for adoption in the U.S.

Smith shared that after reading his first book, Catherine Whelan, an elderly, Boston-based survivor of the Laundries, called him in 2008, and shared her story, then challenged him to do something about it. That call, he said, ignited JFM’s political campaign that launched in 2009; Ireland and the Magdalene Laundries explains what happened next.

“We document how the Irish State continues to elude its responsibilities -- not just to survivors -- but in providing a truthful account of what happened,” said Smith. “It reveals the fundamental flaws in the state's investigation and ensuing ex-gratia redress scheme. Many of the same state tactics are in evidence again following the recent publication of the Mother and Baby Homes Commission report. Accountability, access to records and truth-telling remain elusive goals for so many survivors and their families.”

Co-authors and fellow adoptees Steed and McGettrick, along with adoptee Angela Newsome, founded JFM in 2003, which became Justice for Magdalenes Research in 2013. Its primary mission is to advance public knowledge and research into the Magdalene Laundries.

“This little mustard seed soon grew into an incredibly powerful thorn in the Irish government’s side in demanding justice for all victims and survivors of the Magdalene laundries,” said Steed in the book’s foreword. “This story is about what survivors and victims endured and continue to endure…and how important it is that our story be affixed to the national narrative.”

Two years after JFM brought a case before the UN Committee Against Torture in Geneva, the state issued an official apology in 2013, and a $68-million compensation fund for survivors was established by the Irish government, but the religious orders that operated the Laundries refused politicians’ invitations to contribute. Over 800 women now benefit from the scheme.

“The campaign for justice for the girls and women incarcerated in Magdalene laundries is one of the greatest acts of truth-telling in the recent history of Ireland,” said book reviewer Fintan O’Toole, a columnist for The Irish Times and Orwell Prize winner. “In helping the survivors to reclaim their dignity, this indispensable book also helps the rest of us to reclaim the true meaning of shared citizenship and common humanity.”

Phil Gloudemans | University Communications | July 2021