Photos by Caitlin Cunningham

When Urwa Hameed ’22 was 12 years old and living in Pakistan, her teacher asked to speak with her father. Hameed’s first thought was “I’ve done something bad,” but it turned out that her teacher, a middle-aged Pakistani woman, needed legal advice, and Hameed’s father happened to be a lawyer who did pro-bono work from a tiny office in the village center. Hameed led her teacher there after class.

“She was a Quran teacher and believed in Islam very literally,” Hameed recalled, “so she told me, ‘I’m not going to talk to him directly, I want you to translate all that I have to say.’”

The meeting was Hameed’s first introduction to how women navigate the legal landscape in Pakistan, a predominantly Muslim nation where traditional gender roles dictate most aspects of daily life. It led to her spending more and more time at her father’s office, serving as an intermediary between him and his female clients, many of whom were dealing with stolen inheritance or property. Most days, Hameed was one of the only women in the building, which housed social services for the entire village, but she felt very much in her element.

“I was very engaged in that work,” she said. “I found it very rewarding, very intimate—it was something I really enjoyed doing. So naturally, I wanted to do it when I grew up.”

In December, Hameed will graduate from the Morrissey College of Arts and Sciences with a degree in political science and international studies. Her experience has included many of the tried-and-true elements of college life—study sessions, research papers, karaoke parties—but it’s also empowered Hameed to pursue a deeper understanding of the culture she grew up in, and begin establishing herself as a global advocate for immigrant and women’s rights.

A focus on education

Hameed grew up in Multan, a city in central Pakistan known for its plethora of Sufi shrines, in a house with no running water. Her family (Hameed is the eldest of four children) spoke multiple languages at home: Urdu, Punjabi (her father’s parents were from India), English, and Saraiki, the regional language.

Hameed’s father was passionate about education and sent Hameed to an elementary school located more than two hours from home. Later, dissatisfied with local options, he enrolled her in middle school in Islamabad, the nation’s capital, where she lived away from her family for three years.

In 2011, Hameed’s family moved to Connecticut, joining five of her father’s sisters who lived on the same street. Hameed has fond memories of her early teenage years, which were spent surrounded by extended family members who would drop by unannounced at all hours.

School administrators, unsure how to interpret her school paperwork from Pakistan, used standardized testing to determine Hameed’s grade level, and she became the youngest person in her ninth-grade class by three years. Undaunted, she thrived academically, graduating with a 4.0 GPA. At the age of 14, when most of her American peers were preparing to enter high school, Hameed was accepted at Boston College.

Looking back, Hameed feels she owes much of her success to her father, who emphasized her education and involved her in his work despite cultural pressures to do the opposite.

“He always really supported me, and he brought me into circles where no woman would normally be,” Hameed said. “A lot of that has to do with who I am today.”

Telling women’s stories

At Boston College, Hameed took courses in gender and women’s studies, political science, and sociology, and discovered a passion for research while working as a professor’s assistant. The summer after her sophomore year, she traveled back to Multan and stood outside her father’s old law office. She was awash in memories, but also equipped with a new intellectual framework with which to interpret them. When she returned to the Heights the next fall, Hameed was buzzing with inspiration.

“I realized the highest glass ceiling a woman can break in a country like Pakistan is the political realm,” she said. “For a woman to be able to come up from adverse circumstances and claim one of those positions? That’s a story I wanted to investigate.”

With support from her professors, Hameed spent the next year conducting preliminary research and seeking approval from the Boston College Institutional Review Board to travel to Pakistan and conduct in-person interviews with female politicians. Once the paperwork was in place, she applied for grants and scholarships—ultimately securing five—and began emailing members of the country’s national and provincial assemblies, explaining what she wanted to do.

The response was better than she expected. By July, when Hameed boarded a plane for Islamabad, 20 women had agreed to speak with her about the role education, religion, and financial dependence had played in their political journeys. When she arrived in Pakistan, Hameed was able to secure 30 additional interviews, bringing her total to 50. For the next month, she traveled from state to state, speaking to the politicians in their offices, homes, and in the case of one woman, in the hospital where she serves as the region’s only surgeon.

“There was one woman who was in prison,” said Hameed. “I traveled wherever it was required for me to speak with almost every woman who was serving at the time.”

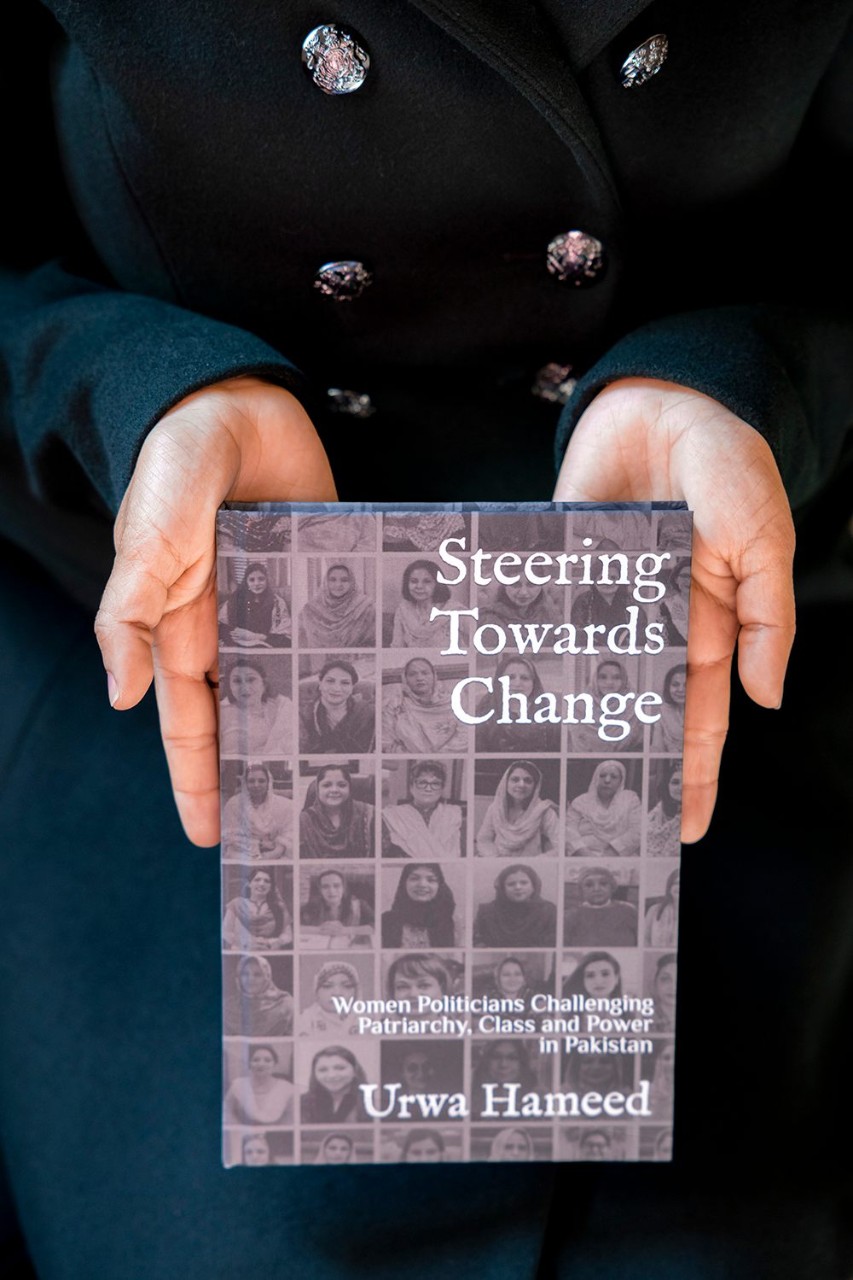

Hameed hopes her book will inspire young girls in her native Pakistan.

Hameed conducted her interviews in Urdu and used her knowledge of regional customs to put her subjects at ease. In more conservative areas, she donned a traditional South-Asian outfit known as a shalwar kameez and a full hijab, but in liberal Islamabad, she knew politicians would fear being judged by someone in conservative dress. Each woman signed a translated consent form, but many waited until after their interviews when they were confident their responses weren’t misinterpreted.

“They had to be able to trust me,” Hameed said. “I don’t think they’d be able to share that narrative with anyone they perceived as an outsider because as Muslim women they tread cautiously.”

Hameed treated each session as an opportunity to conduct qualitative research, but she was also moved by the personal stories of women who had overcome poverty, patriarchal oppression, and abuse to achieve their political goals. One of the most powerful politicians Hameed interviewed was married at the age of 14 and had given birth to four children by her early 20s.

Around her 43rd interview, Hameed began considering the possibility of compiling the stories into a book that could serve as inspiration for young Pakistani girls like herself, and offer insights to fellow researchers. She returned to the U.S. and started editing. In October, Steering Towards Change hit Amazon’s virtual shelves in English and Urdu, its pages containing the first-person accounts of 45 women “challenging patriarchy, class, and power in Pakistan.”

Future changemaker

When Hameed sees a problem, she can’t help but try to fix it. Last winter, she realized that BC had never had two women of color leading its student government, so she launched a campaign for student body president (and ultimately came in second). As a teenager living in Connecticut, she spent weekends helping her mother’s coworkers who didn’t speak English file governmental paperwork. When her language skills weren’t enough, Hameed contacted the Internal Revenue Service.

“I told them ‘this is something that’s really bad in my community,’” she recalled. “The government offers translation services in Spanish and Arabic and a few other languages but that’s it. If you want more help, it’s a really cumbersome process.”

With IRS support, Hameed launched Free Tax Prep, Inc., a nonprofit connecting immigrants with volunteer translators in more than 40 languages. Two of her co-directors are fellow Boston College students.

Hameed is currently in the process of applying to Boston College Law School, where she hopes to study international law. If she’s accepted, she’ll begin her law journey at the age of 19 and begin amassing the skills to make an even bigger impact. Someday, she envisions working for an intergovernmental organization like the United Nations, promoting women’s rights around the world.

“I don’t exactly know what that position would look like, but I know I want to take it up a notch from advocacy,” she explained. “I want to be able to do something concrete to fix the injustices that happen every day.”

Alix Hackett | University Communications | November 2021