For I Have Sinned

the rise and fall of Catholic confession in America

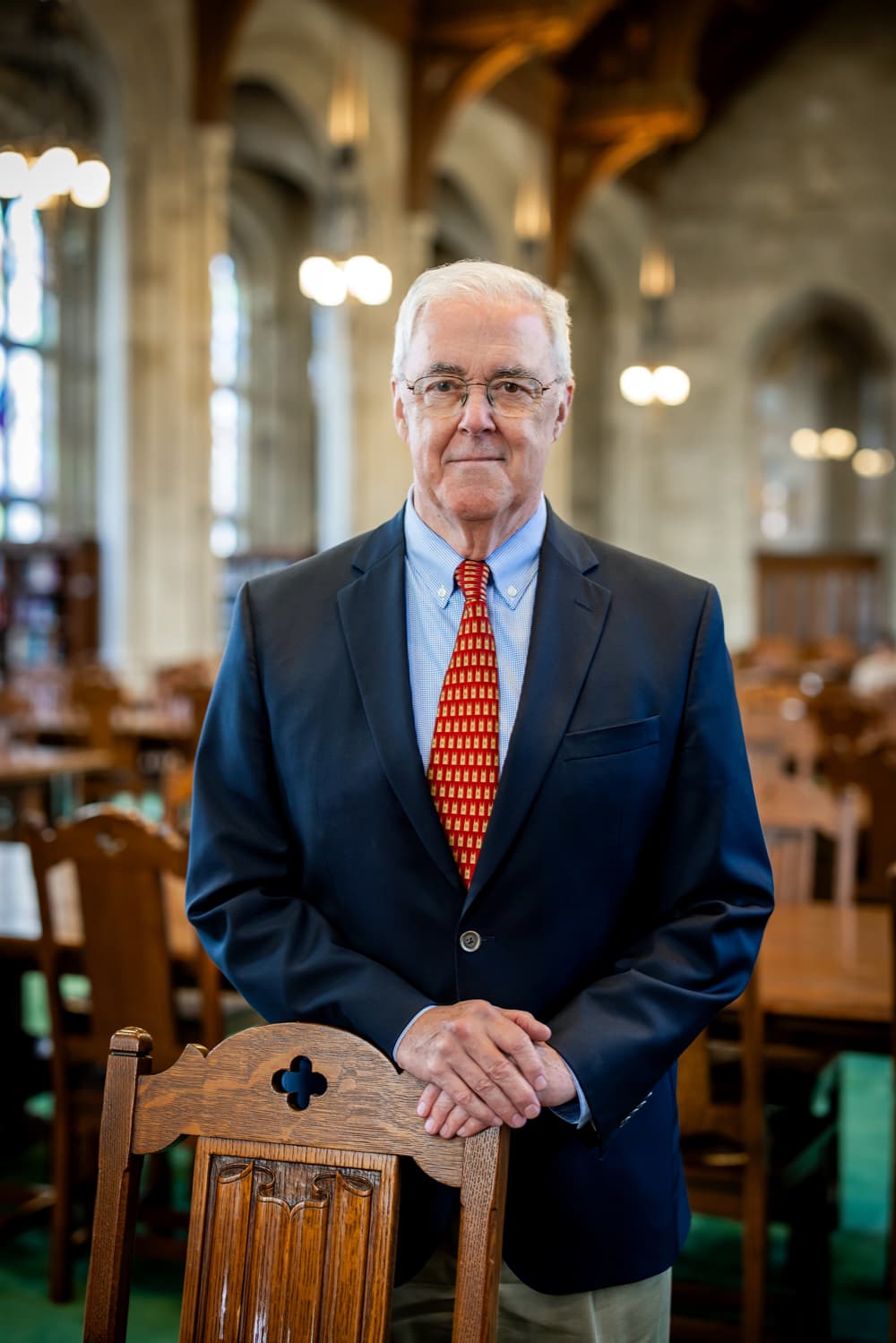

For generations, American Catholics regularly went to confession, a sacred rite that offers a way to reconcile with God and the Church. But starting in the 1970s, they stopped, and in his new book, For I Have Sinned: The Rise and Fall of Catholic Confession in America, University Historian James O’Toole investigates why.

Sprinkled throughout with stories and first-hand accounts of confession from lay people and priests alike, For I Have Sinned recounts shifting perspectives and policies on a practice that is a distinguishing marker for Catholics—a way to measure and acknowledge a person’s sins.

For I Have Sinned was born of a separate project of O’Toole’s, a book about an interracial family that included a number of priests and sisters, among them a Jesuit priest named Patrick Healy. Fr. Healy, O’Toole discovered, kept meticulous records of confession in his parish, adding up totals every week and every month.

“Fr. Healy typically heard confessions on Saturday afternoons and evenings, and he kept the pace in his diary,” O’Toole explained. “He’d write things like ‘Today was slack at only 88 confessions.’”

The records showed O’Toole that confession—a practice conducted in private—was possible to research.

“I was able to chart the decline of confession by looking at the times parishes set aside on a regular basis to hear confessions. At the typical parish in the early 20th century, there’d be five or six hours available on a Saturday.

“But priests aren’t going to sit in the box if no one is coming. So you can look at the decline of confession as those hours shrink.”

For example, where in the late 1950s and 1960s a church might hear confessions throughout the day on Saturdays, today that same church might only schedule confessions for one hour. And where the number of confessions heard weekly by a priest in that time might have totaled in the hundreds, nowadays that number is more likely to be counted on one or two hands.

For I Have Sinned by James O'Toole invites the reader to consider how Catholics can continue to understand and express their ideals even as the Church evolves.

Once he started looking, O’Toole found more and more sources that documented confession, like church pamphlets and catechisms. According to O’Toole, these are the types of sources that are everywhere and then nowhere. Luckily, Boston College’s John J. Burns Library has extensive holdings, particularly in its Liturgy and Life Collection.

“Running into things like Fr. Healy’s diaries and the times a church has set aside for confession showed it was possible to write about the subject. And the sources that are available for this in the Burns Library are absolutely terrific.”

But more than data points, the confessional records also offered a window into what laypeople were doing, and O’Toole wanted to find out why they chose, or chose not, to go to confession.

As O’Toole explains, going to confession, while a defining part of Catholicism, was always hard: not only because of the embarrassment of seeing one’s neighbors while sharing wrongdoings, but also because sin is so intricately defined that it can be difficult to articulate in the confessional.

Still, O’Toole is hesitant to say anything is inevitable, including the decline of confession. Instead, he points out what changed: the emergence of psychology, the Church’s stance on contraception, an evolving sense of sin, and recognition of sexual abuse, among other nuanced factors. He also notes that at risk of loss is a framework for assessing individual behavior, good and bad.

O’Toole happily points out though, that as a historian, it’s not his job to figure out where the Catholic Church should go from here. Right now, he’s pleased to have finally completed the book.

“It feels great to be finished,” he shared. “I’ve been thinking about this project for a long time.”

For O’Toole, the most enjoyable part of a project like For I Have Sinned is the historical, archival work. But perhaps a particularly poignant moment of his research was returning to his childhood church to compare current practice with his memories.

“Back then, two or three priests heard confessions for five hours on Saturdays,” O’Toole reflected. “Today, there is one priest and only one hour for confessions.”

In the hour O’Toole spent visiting, just four people confessed. But there were encouraging signs—O’Toole saw that the school was expanded, and the church itself was in very good condition.

While O’Toole is not in the business of forecasting the future, that is where For I Have Sinned ends: inviting the reader to consider how Catholics can continue to understand and express their ideals even as the Church evolves.