Keeping the Republic

Throughout its history, the United States Constitution has led a dual existence as one of the country’s most prized—and most criticized—documents.

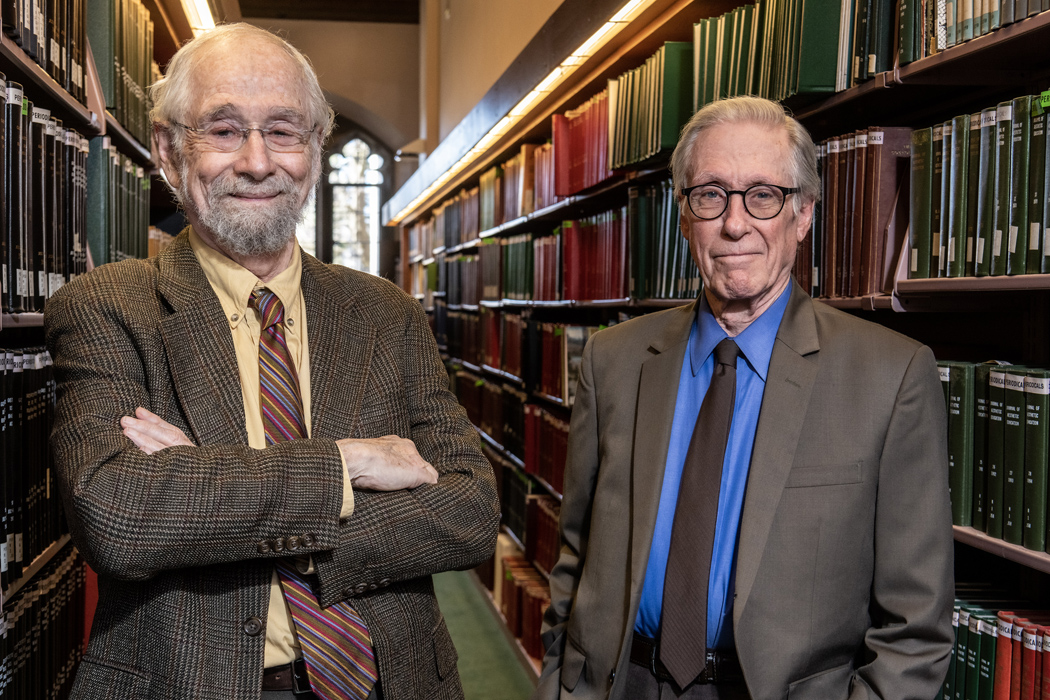

In their new book, Keeping the Republic: A Defense of American Constitutionalism, Professors of Political Science Dennis Hale and Marc Landy examine why the Constitution has come under fire, whether from notable statesmen, writers, pundits, and academics or ordinary American citizens—and they explain why that criticism is misplaced.

By and large, the complaints about the Constitution stem from frustration with perceived obstacles to achieving political or legislative aims, say Landy and Hale. Depending on the specific issue, suggested remedies include doing away with the U.S. Senate, the Electoral College, the presidential veto, and/or federalism, or reforming the U.S. Supreme Court to make it more democratic—all of these decried as elements of an obsolete or undemocratic Constitution that hampers the process of governing.

As the authors note, actions have sometimes replaced words in diminishing or bypassing the Constitution, including by presidents—from Truman embarking on the Korean War without any congressional approval to Reagan’s Iran-contra scandal to Obama’s executive order granting working papers to illegal immigrants, and Biden’s voting reform bill.

Keeping the Republic argues that, by placing effective limits on the exercise of power, the Constitution is simply doing the job it was created to do: providing for a free government. The Constitution is the difference between a country in which the people rule, and one in which people can do anything they want, say Hale and Landy, and the restrictions it sets on American political life is not a problem, but a solution to a problem.

“We felt, based on what we were reading or hearing, that the critics didn’t really understand the Constitution, or more broadly, the idea of a Constitution,” said Hale. “They don’t like the shape and substance of the Constitution, they want to change it, or just get rid of it. The problem is, they have nothing to substitute for it.”

Critics of the Constitution, said Landy, often blame it for “things that are not a result, or the fault, of the Constitution”—namely the problems inherent in a modern state: size, diversity, and the need for a common, national defense.

Keeping the Republic is the first book co-authored by Hale and Landy, who have collaborated as editors on two volumes of essays as well as articles for Real Clear Politics/Public Affairs and The Claremont Review of Books. Friends since their undergraduate years at Oberlin College (“We’ve been in each other’s hair ever since,” as Landy puts it), the pair joined the Boston College faculty within three years of each other in the 1970s. To watch them converse is to see two people whose differing sociopolitical views—Landy tracks to the left of Hale—don’t lessen their obvious mutual respect for one another, or their ability to hold civil conversations and find common ground.

Although they have been in the same department for decades, say Hale and Landy, their writing partnership didn’t truly coalesce until they wound up in adjoining offices several years ago. When a raft of Constitutional criticism flowered from within academia and the media, the two began talking about it, then decided to write about it.

“We sat in Dennis’s office: I would talk and he would type,” recalled Landy, characterizing their co-authorship as a “Rodgers and Hammerstein” type of collaboration.

Landy and Hale include a clarification and a caveat early on in Keeping the Republic: Although their book is not an attempt to investigate every potential threat to the constitutional order, they acknowledge an existential one posed by Donald Trump, as reflected by his continual overstatement of his powers while president and his refusal to accept the 2020 election results. However, they argue that his presence in American politics is the end-product of numerous attempts down through U.S. history—including some from what would be considered a liberal/progressive standpoint—to circumvent or lessen constitutional oversight.

Setting a context for this historical retrospective, Hale and Landy analyze the concept of modernity and how it applied to the age and milieu in which the framers of the Constitution lived. Influenced by philosophers like Hobbes, Locke, Montesquieu, and Hume, the framers were “at once ambitious and realistic,” the authors write: “They accepted human beings as they were and sought to construct a political framework for a modern republic grounded in human nature, considering both its strengths and weaknesses—paying special attention to the particular strengths and weaknesses of Americans.”

The key to the Constitution, say Landy and Hale, is that it establishes a republic, not a democracy—perhaps an underappreciated nuance but an important one, in that a republic guards individual rights against the will of the majority.

“The Constitution creates a government meant to be balanced but intentional in its parts,” explained Hale. “In a republic, you need more than a simple majority to get things done. The Constitution builds incentive to reach and broaden coalitions.”

For much of the 21st century, as American politics have become ever more polarized, the capacity—and even the willingness—for opposing parties to compromise has waned, to the extent that Congress has become merely an arena for partisan bickering and virtue signaling, said Hale and Landy.

Rather than prescribe specific solutions, Landy and Hale devote the book’s final chapter to “thinking constitutionally”—a recommendation that citizens attain a true understanding of the Constitution and its aims, which is to foster liberty, justice, equality, prosperity, security, and civic comity. This means taking a long view, they explain, and realizing that what may have been regarded as landmark political achievements, such as the New Deal or the Great Society, ultimately contributed to the diminution of the Constitution, and America’s ability to effectively govern itself.

“We didn’t have to become the most powerful nation on Earth after World War II, but that’s how it turned out,” said Hale. “Obviously, achieving that status brings a unique set of political, social, and other challenges, and as a country we’ve struggled with these. But ultimately, the Constitution is the best safeguard against making choices we’d come to regret.”