Kids and Disasters

As catastrophic events become more frequent, BC's Betty Lai is researching how to promote recovery and resilience in children.

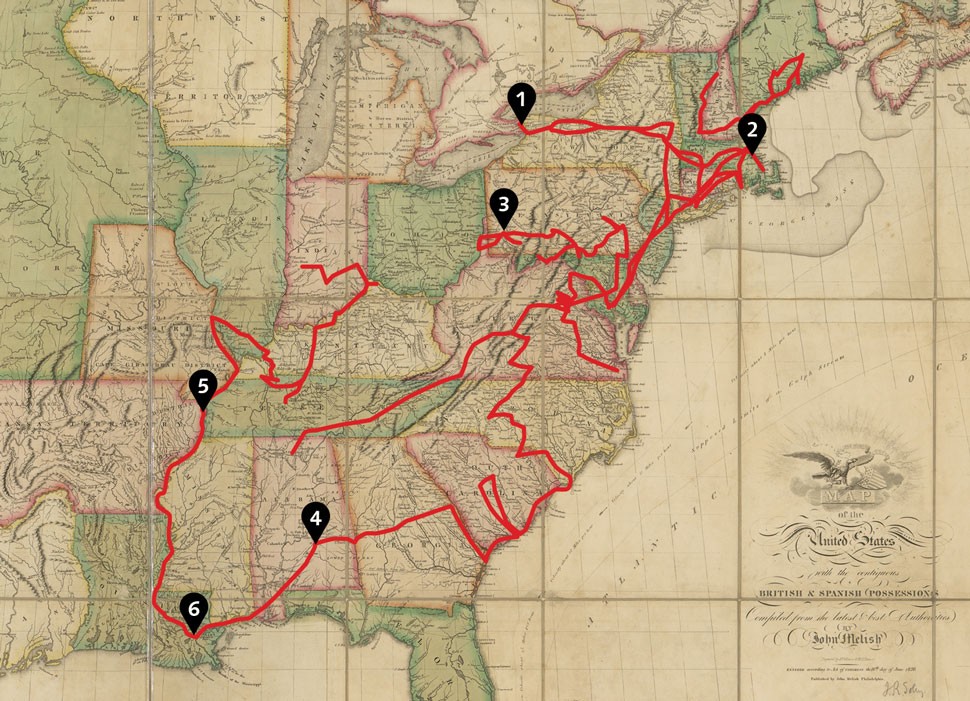

The routes that writer Anne Royall traveled on U.S. Postal Service-owned stagecoaches.

Map: Library of Congress

How the Post Office Shaped American Literature

BC Professor Christy Pottroff explores snail mail’s contribution to our literary tradition.

Anne Royall was penniless. Following the death of her husband William in 1812, her in-laws claimed his estate and left her with virtually nothing. Royall may have been poor, single, and in her 50s, but she was resourceful. She eventually wound up traveling the country on U.S. Postal Service–owned stagecoaches on a shoestring, recording what she saw and making history as one of the country’s first female journalists. “It was just a remarkably savvy strategy,” said Christy Pottroff, an assistant professor of English at Boston College. “The post office really underwrote her entire career.”

In fact, as Pottroff has explored in her research, the U.S. Postal Service was instrumental in the careers of many 19th-century writers, especially marginalized ones. It was a common means of transportation, Pottroff said, in part because hitching a ride with a USPS stagecoach was affordable. This facilitated the advent of a popular genre in American literature at the time, travel writing. “Anyone who did travel writing in the early 19th century was most likely writing in the seat of the stagecoach that was delivering the mail,” she said.

Royall was one of those writers, even though riding a stagecoach must have been “terrifying” for a single woman at the time, Pottroff said. Everywhere Royall went, she interviewed locals, and then she wrote books—Sketches of History, Life, and Manners in the United States, Letters from Alabama, and others—about her travels. Because they were so long, her books were too expensive to sell through the mail, so she loaded them in a trunk and sold them around the country using the same stagecoach routes.

But the USPS did more than transport writers: it helped to disseminate their literature. While Royall’s contemporaries such as Nathaniel Hawthorne and Herman Melville—both wealthy white men—had access to publishing houses that could print and distribute long works, everyone else had to get creative. If you were a writer looking to distribute your work for cheap, distribution via mail, and in short pieces, was the way to go.

That’s why, when the Black author Henry “Box” Brown decided to circulate his life’s story, he did so in the form of a mailed pamphlet. (Coincidentally, he got the nickname “Box” for mailing himself to freedom from Richmond to Philadelphia in a box.) “He was able to mail his narrative and share his experience by writing a story that fit the parameters of the post office itself,” Pottroff said. And when the famed essayist Judith Sargent Murray couldn’t find an established publisher to print her books, she wrote shorter essays, letters, and plays that ran in newspapers and magazines delivered by the USPS.

Whether writers were using the post office for transportation or distribution, they found themselves limited to places where post offices existed. Luckily, as the 19th century progressed, so did the postal service’s expansion plans. By the end of the Civil War, there were 37,000 post offices in the United States. It wasn’t quite the reach of broadband internet, but nearly everyone in the country was eventually connected to each other, regardless of their race, gender, or social status. “Looking back to the 19th century, we see a lot of innovative ways the post office was used to facilitate broad public good,” Pottroff said. “We may not use the postal service for travel anymore—or even use it for mail. But when you read one of the great American storytellers, its influence is felt.”

The 19th-century travel writer Anne Royall rode around the United States on USPS stagecoaches, jotting down her impressions of the people and places she encountered:

1. Niagara Falls: “Nothing under Heaven can be more sublime! It astonishes, it transports, it thunders, it deafens!”

2. Boston: “The streets are very short, narrow, and crooked, and the houses are so high (many of them five stories), that one seems buried alive.”

3. Pittsburgh: “But Pittsburg [sic] enjoys still more of the bounties of nature. [It is] in the midst of endless beds of coal, iron and salt, at its doors, and the trade of three fine rivers, to say nothing of its industry and skill in the application of its mechanical and physical powers.”

4. Montgomery, Alabama: “There are a great many goats in Montgomery, and Mr. Beacher would catch the goats, and stick a tract on each horn, and send them forth to spread the gospel—much honester Missionaries, I must confess, and much more respectable, than the two-legged Missionaries—these told no lies.”

5. Mississippi River: “The mighty river, itself, is an object of deep interest and untiring beauty, and always sublime. Its serpentine figure renders it always beautiful. The points of land caused by its windings, which are seen far ahead, assume every figure and every shade, rising one above another.”

6. New Orleans: "All I can say of it is that it is one blaze of flowers, with groves and gardens of incomprehensible beauty, doubtless the most finished picture of landscape art in the world—not an atom of room left for improvement."