|

click on icons for HOME and Session

CONTENTS pages

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

2: Shared Origins, Diverse Roads |

||

| INFORMATION SHEET | ||

|

click on icons for HOME and Session

CONTENTS pages

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

2: Shared Origins, Diverse Roads |

||

| INFORMATION SHEET | ||

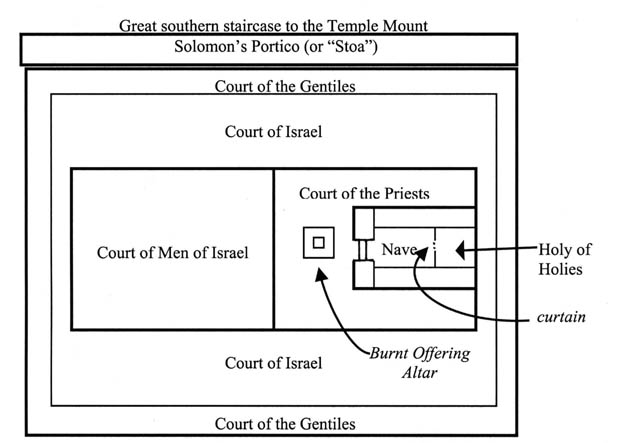

The Second Temple as Expanded by Herod

|

This model looks northeast toward the Temple. To the left is the Antonia Fortress, to the right is Solomon's Portico. In the Center is the Holy of Holies. Robinson's Arch is visible in the nearest corner of the mount. |

First-century Jerusalem was dominated by the mammoth expansions to the Temple Mount begun by Herod the Great in 20 BCE and not completed until shortly before the outbreak of the Great Revolt in 66 CE. Enormous retaining walls were constructed to double the plateau on top of the Mount to forty acres. The Antonia Fortress (named for Mark Antony) guarded the northwest corner of the Mount, where it was most vulnerable to assault. A bridge over the Tyropeaen Valley, whose end point is marked today by Wilson’s Arch, permitted direct access to the Temple Mount from the Upper City. Robinson’s Arch, in the southwest corner of the Temple Mount, supported stairs up from the Lower City. Most pilgrims, however, would gain access to the Temple Mount by way of the great southern staircase. Most of the city, including the Temple Mount, was destroyed by Roman legions in 70 C.E. Today’s Western Wall, a remnant of Herod’s retaining wall, is found between Wilson’s and Robinson’s Arches.

|

|

Temple Liturgies

The major ritual that took place in the Temple was sacrifice. Sacrifice in the Hebrew/Jewish tradition was the offering of plants or animals to God. Blood was considered to be a purifying, life-energizing liquid that was the vessel of God’s ruach or Spirit. The ritual use of blood could establish or restore or reinvigorate relationships. Wealthier persons were expected to present more valuable offerings. Poor people could give birds or even flour. Entrance to the Temple precincts required ritual purity and as one moved into its inner courts access became more restricted. Ritual purity required cleanliness and the absence of bodily emissions in order to draw near to the divine presence. The Holy of Holies could only be entered by the High Priest once a year on Yom Kippur.

Types of Sacrifices Offered in the Temple

Burnt Offering or Holocaust

This was a sacrifice in which an animal or bird was slain, skinned, and cleaned as if for a meal, and then burned completely on the burnt-offering altar. The flame and smoke of the offering rising toward heaven was seen as life being totally given back to God. This ritual declared that all things belonged to God. It was the holiest of all sacrifices.

Peace Offering

In this sacrifice only part of the animal was burned on the altar to God. The rest of the meal was taken to be eaten by the priest and the offerer. This sacrifice was offered to praise or thank God, to fulfill some promise made by the offerer, or to establish a covenant among two or more people and God.

Sin or Guilt Offering

In these sacrifices, no meat would be returned to the offerer to eat. Part was burned for God, and the priest took the rest. Blood from the sacrifice was rubbed on the altar and poured around its base to show that life with God was being restored.

The Showbread

This was an offering of twelve cakes of fine flour. These would be accepted by the priests every Sabbath and placed on a table in the nave of the Temple. Incense or perfume presented with the cakes would be burned on the incense altar. The twelve cakes signified the covenant between God and the twelve tribes of Israel.

The Three Pilgrimage Festivals

Passover (Pesach)

In the first-century, Passover memorialized the Exodus from Egypt. Although details are sketchy it is likely that in Second Temple times a seven-day festival was celebrated which began with the slaughtering of lambs in the Temple. The meat was then consumed by families during a meal that included unleavened bread (matzah) and bitter herbs.

Pentecost (Shavuot or Weeks)

Occurring fifty days after Passover, this feast may have originally marked the end of the grain harvest. In Second Temple times it celebrated God’s gift of the Torah to Moses on Mount Sinai. It was therefore a covenant renewal feast and perhaps was observed with a ceremony similar to that described in Exodus 24:3-8.

Tabernacles (Sukkot or Booths)

The eight-day feast originated as an autumnal harvest festival and became associated with prayers for rain. For seven mornings, a solemn procession went to the spring of Gihon to the southeast of the Temple Mount where a priest filled a golden pitcher with water. Then the procession returned up to the Temple carrying branches (reminiscent of temporary shacks used in the field during harvest time) and lemons or citrons symbolizing the harvest. The men processed around the burnt offering altar while the priest poured the water through a silver funnel from the altar onto the ground below. On the seventh day, the altar was circled seven times. On the first night, and maybe the others as well, four giant golden candlesticks, topped by golden bowls in which floated wicks made from the girdles of the priests, were lighted in the Court of Israel. It was said that all Jerusalem basked in the light that shone from the Court.

The Ministry of Jesus

The phrase "Kingdom [or Reign] of God" seems to be a distinctive phrase of Jesus, although the idea of God's kingly rule appears often in Israel's scriptures. All his deeds and words seem to flow from the conviction that God's rule over the earth was beginning:

Certain beliefs emerged among Jesus' Jewish followers after experiencing him as "raised." Their developing ideas set the foundations for what would become a separate religious community.

In raising Jesus, God has given divine approval of everything Jesus did and said.

Therefore, the Reign of God must indeed be commencing as Jesus had said. His exaltation is the first of a series of anticipated events that must be about to occur:

the restoration of Israel (e.g., Acts 1:6)

the extension of salvation to the Gentiles (an expectation confirmed when preaching about Jesus is warmly welcomed by Gentile "God-fearers")

the general resurrection of all the dead (see Matthew 27:51-53)

Communities of those who believed that the Crucified One had been exalted assemble. They seek to be united in radical equality and love, experiencing the New Life of the Spirit of the Raised Lord.

In order to comprehend why a crucifixion victim was the agent of God’s plans, the scriptures of ancient Israel were scoured for insight and read in unprecedented ways. The suffering servant songs in Isaiah and Psalm 22 provided particularly fruitful texts.

Jesus, the celestially-enthroned Lord, the first fruits of the dead, has the divine power of judgment. He will soon return in triumph to mete out justice and to establish the Reign of God (e.g., 1 Thessalonians 4:13-5:11; Mark 14:62; Acts 3:19-21).

Jesus followers began to sing and pray about him at their continuing fellowship meals as the unique Lord and Son of God.

Prominent Features of Rabbinic Judaism (as put in writing by the rabbis in the centuries after the destruction of the Second Temple)

Prayer, the performance of God's commands (mitzvot), and the study of the Torah bring holiness, the forgiveness of sins, and constitute an acceptable sacrifice to the Lord. These activities replace the Temple sacrificial system as the means to access God.

Religious observances increasingly occur in the context of the family and the home. The pilgrimage festivals are adapted to a non-Temple context.

Questions and commentaries, and responses to other's answers and comments, become the primary activity of the rabbis. A developing body of written wisdom and reflection continues to be composed down to the present day.

Principal Rabbinic Texts

The Mishnah ("oral teaching") was compiled and edited around 200 C.E. in Sepphoris in the Galilee. Understood as the first written expression of the "oral law" that had circulated among some Jews for many years, it is a collection of laws and ethics organized in six sections or "orders." The orders are subdivided into "tractates," totaling sixty-three tractates in the Mishnah as a whole.

The Midrash is comprised of homiletic, theological, moral, and legal expositions of the bible composed around the same time as the Mishnah and Gemara.

The Gemara ("completion") consists of rabbinic texts that expound upon the Mishnah. In a broad sense, the Mishnah and Gemara together make up the Talmud or Oral Law, which is considered to have the same divine authority as the the Written Law, the Torah.

The Talmud ("study") consists of the Mishnah and the Gemara, the rabbinic debates on the Mishnah. There are actually two Talmuds: the Yerushalmi, or the Talmud of the Land of Israel, probably edited in Tiberias in the Galilee around 300-400 C.E., and the Babylonian Talmud or Bavli, composed in Babylon around 500-600 C.E.. Both discussed the Mishnah and its scriptural basis in the Torah, but the Bavli joined Torah and Mishnah together more thoroughly and was more expansive. Jews for centuries have, therefore, approached the Written Law, the Torah, by way of the Oral Law, and most especially through the Bavli.

The rabbinic texts contain these types of types of writings:

Halakhah ("going," "walking") - Jewish law as expounded by the Talmudic sages

Haggadah (or Aggadah) - non-legal materials consisting of sermons, ethical and moral instruction, and folklore.

The six orders of the Mishnah are:

1. Zera'im ("seeds") deals with laws relating to agriculture, contains eleven tractates including one on blessings and prayers.

2. Mo'ed ("season") contains twelve tractates about the festivals and the sabbath, including a discussion of what is considered work prohibited on sabbath.

3. Nashim ("women") addresses laws of marriage and divorce and has seven tractates.

4. Nezikin ("damages") has ten tractates concerned with civil law.

5. Kodashim ("sanctities") discusses the sacrifices and offerings of the Temple in eleven tractates.

6. Tohoroth ("purities") has twelve tractates dealing with ritual purity.