Jobs Well Done

Recently retired as one of BC’s longest-serving faculty members, David Twomey ’62, JD’68, reflects on a legendary career in law and labor.

Illustrations by Nadia Radic

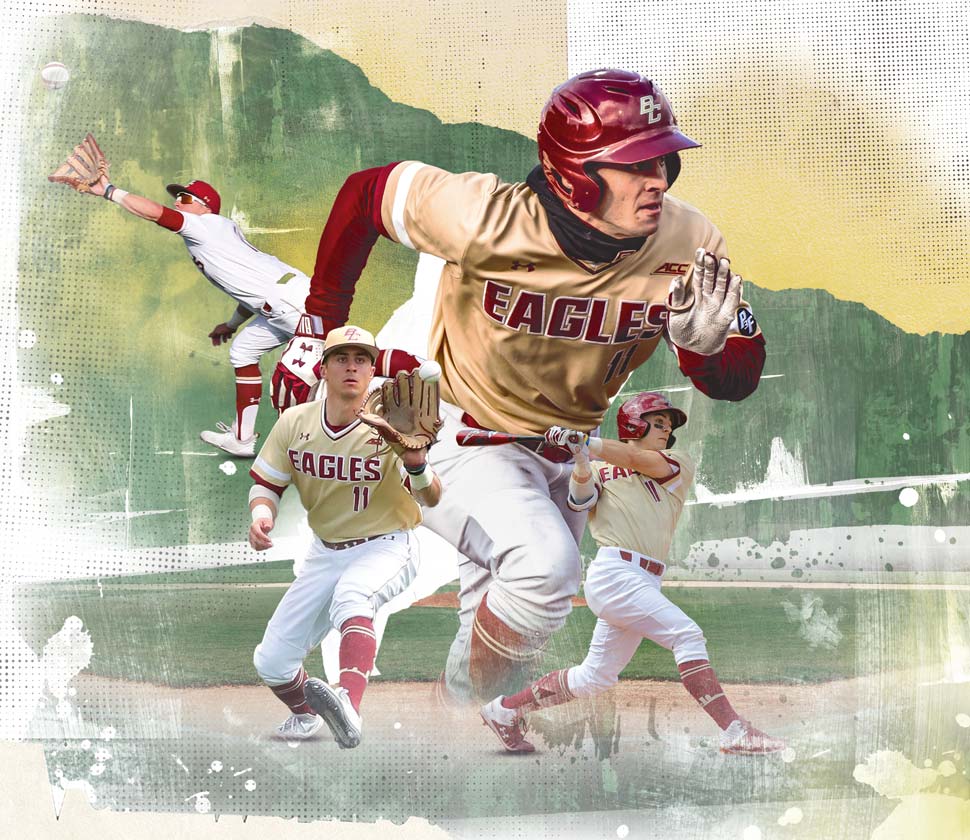

The Grinder

Sal Frelick ’22 was an undersized high school athlete with a ferocious competitive drive…and exactly one offer to play college baseball. Here’s how he hustled his way to becoming one of the best ballplayers in BC history, and an emerging star for the Milwaukee Brewers.

The sun set in Nashville, and Sal Frelick was on a hot streak. Frelick, in his second full season in the Milwaukee Brewers minor-league system, had homered a couple of days earlier, and now he had just helped his Nashville Sounds beat the Jacksonville Jumbo Shrimp 17–3. At ten o’clock, after the last pitch was thrown, Frelick sat shirtless in the clubhouse, eating a late dinner with his teammates, when his manager walked in.

“Sal, you sure you’re OK to play tomorrow?” the manager asked. Frelick nodded. “Well, you ain’t playing here,” his coach said. “You’re going to the big leagues.”

It’s always an unforgettable moment when a minor-league prospect learns he’s being called up to the majors, but what made it all the more amazing for the undersized Frelick was how unlikely the whole thing had once seemed. Growing up in Lexington, Massachusetts, Frelick had been an excellent multi-sport athlete. But a professional ballplayer? Not likely for a five-foot-eight, 150-pound high school freshman.

But the former BC baseball head coach Mike Gambino saw in Frelick an intense, unrelenting competitive drive that transcended his small stature. He saw the potential for greatness. “Sal has this raw athleticism,” Gambino explained. “He plays tremendously hard. And he plays with this unbridled joy that’s just amazing to watch.” Gambino, seeing what many others missed, began his recruiting pitch, and by the time Frelick was a high school sophomore, he’d committed to play for the Eagles.

Frelick first took the field at BC in 2019, and immediately began playing like a star. In his three seasons at Boston College, he hit .345, smacked twenty-seven doubles, stole thirty-eight bases, and played sparkling outfield defense. In 2021, he was named to the All-ACC first team and selected by the Brewers with the fifteenth pick in the first round of the Major League Baseball draft, receiving a $4 million signing bonus. Tony Sanchez, who was selected fourth by the Pittsburgh Pirates in 2009, is the only BC player to have gone higher in the draft.

And now, after a year and a half of grinding his way through the Brewers’ minor-league system, of taking fourteen-hour bus rides to play in front of empty seats and hoping along with every guy next to him to get that chance to step up to bat in the majors, it was actually about to happen.

Frelick called his parents. “He doesn’t say anything,” recalled his father, Jeff Frelick. “There’s an awkward pause for like thirty, forty seconds. We thought he was hurt. We thought it was bad news. And then he says, ‘I’m going up to Milwaukee.’”

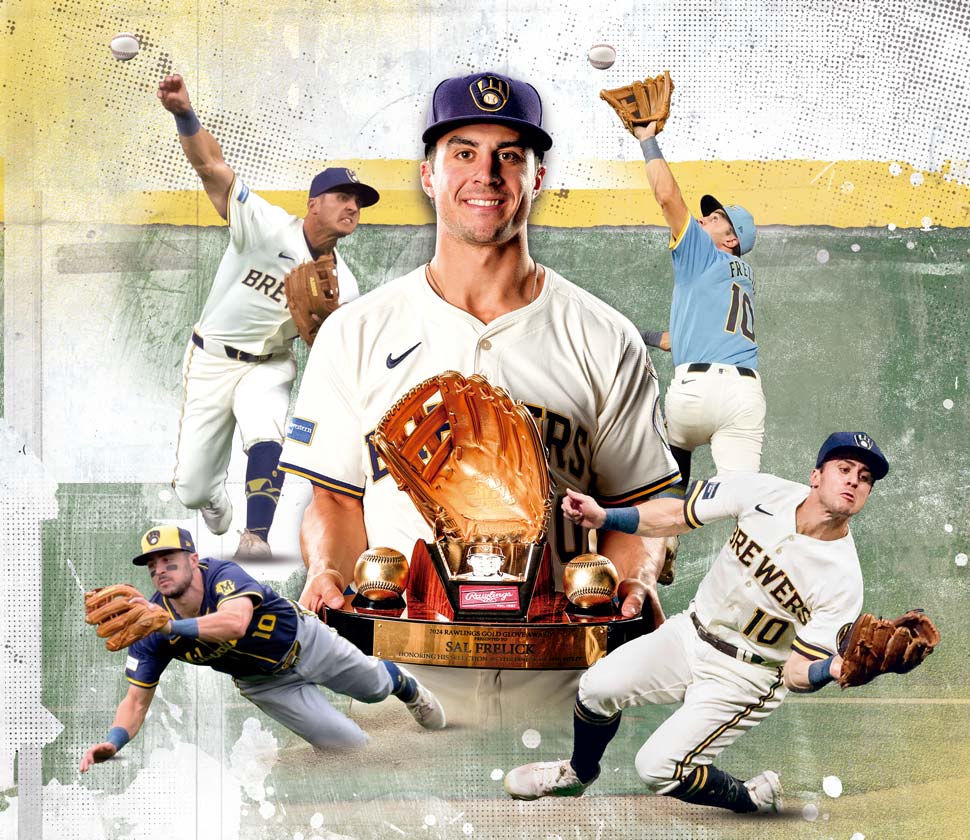

In April, Frelick and I sat in the dugout before an early-season game at American Family Field in Milwaukee. In his two-plus years in the big leagues, Frelick has emerged as a budding star. In 2024, he won the Gold Glove Award as the top defensive right fielder in the National League, making only three errors in 278 chances and leading his position in both runs saved and outs above average. He was going to be presented with his Gold Glove Award prior to the start of today’s game, but for now, the Brewers were taking batting practice in the still-empty stadium.

“I literally had no clue,” he said of winning the Gold Glove. “They called me maybe a week into the off-season and told me I won, and I was like, ‘What?’” It was striking how much talking to Frelick, who was wearing a pregame hoodie and headband, seemed like just hanging out with another BC alum, a guy who lived on Upper, majored in marketing and minored in religious studies, went to Mass at St. Ignatius. If you passed him on the street, you probably wouldn’t think he was a professional athlete. He’s still just five-foot-eight and 180 pounds, fairly small by normal standards, much less those of major-league ballplayers. And with his unassuming, friendly demeanor, he comes across more like the nice Italian guy who lives down the block than a Gold Glove winner.

But when he steps on the field, that friendly expression is replaced by a jaw-clenching intensity. He’s a scrapper. He goes all out with an endearing lack of interest in his personal safety, whether he’s sprinting toward a wall for one of his spectacular catches or sliding hard into the bag while stealing a base. By the fourth inning, you can expect to see his uniform covered chest-to-ankles in dirt and grass stains. Little wonder that the player he grew up idolizing was the similarly compact and hard-nosed Boston Red Sox spark plug Dustin Pedroia.

Frelick laughed when I referred to him as a fan favorite, but it’s undeniable that with his talent and playing style he’s developing a following alongside Brewers stars like Christian Yelich and Jackson Chourio. When his name is announced, the fans cheer a little harder.

“Different people scream when Yelich runs out versus when I run out,” Frelick said with a laugh. “He gets a lot of teenage girls, young kids. The demographic I attract is males over the age of sixty-five. I think they like that I’m always flying into walls unnecessarily.”

Patty Frelick calls her son a scooch, Italian slang meaning a pain in the…neck.“ He was the kid who would get away from me,” she said of Sal, the middle of her three children. “I would be holding the baby, and Sal would be doing somersaults and dashing and darting, and I would try to catch him and I couldn’t, and I’d start laughing.”

There was one obvious outlet for all that energy—sports, and lots of them. All three Frelick kids were multi-sport athletes from the moment they could run. “It was like a game every night, every season,” Sal recalled, starting with T-ball and continuing nonstop until the day he graduated from Lexington High School. By the time he was in middle school, his three main sports were football, hockey, and baseball. He was very good at all three, but for a kid his size, they seemed more like a path to a good college than a career. “We didn’t think that he was a pro player in tenth, eleventh grade, anything like that,” said his father.

“My mindset,” Frelick recalled, “was just, I want to play whatever sport I can the longest.” BC was the only school that wanted him to play baseball, but Gambino, who is now the head coach at Penn State, was steadfast in his belief in Frelick’s potential. “People say that he’s undersized, but I never looked at him as undersized because he’s so explosive,” Gambino said. “He has speed, athleticism, tremendous bat-to-ball skills. But the thing I kept seeing when I watched him play was that he had this feel for how to beat you on the baseball field.”

With no other baseball offers, Frelick committed to BC early, the summer before his sophomore year. The decision was partly academic—assuming baseball stopped after college, he’d have a valuable degree from a great school. Though he’d signed with BC to play baseball, Frelick continued with his other sports in high school—and before long was actually starting to look more like a football than a baseball prospect. Despite his diminutive height, he played quarterback and defensive back, passing for 1,940 yards and thirty touchdowns in his senior year, and rushing for another 1,779 yards and twenty touchdowns. He was named Gatorade’s 2017–2018 Massachusetts player of the year. Frelick was so good on the gridiron that soon former BC head football coach Steve Addazio was also offering him a scholarship.

“I was like, ‘Hell, yeah. I get to play both? That’s awesome,’” Frelick recalled. “Coach Gambino called me. He didn’t know that they’d offered me football.” Gambino was not pleased.

“If you’re coming here, you’re just playing baseball,” he told his young recruit. “You’re not playing football.”

“In my head,” Frelick recalled, “I’m like, Screw that.” He considered ditching BC for a school that would let him play football and baseball. He told his high school football coach to let other colleges know he was open to offers—and quite a few came in. But then Gambino had another talk with him.

”Could you play football in college?” Gambino asked him. “Yeah, sure. But are you looking past that?”

Frelick realized that he wasn’t thinking big enough. “I wasn’t looking past college at all,” he recalled. Gambino “was the first one who thought I really had a shot at pro baseball. I thought he was crazy.” Crazy or not, Gambino convinced him, and Frelick enrolled at BC in the fall of 2018. But his college career got off to a frustrating start. He took a cleat to the ankle during a practice, effectively sidelining him for most of the preseason. By opening day he was healthy again, but with so few preseason at-bats, he assumed he would be starting the year on the bench. Instead, Gambino put him in at designated hitter. “I saw my name in the lineup that morning, and I was pretty surprised,” Frelick recalled. So was the rest of the team. There was some grumbling in the dugout.

“Nobody was going to say it, but I remember the feeling, especially with the older guys,” Gambino said. “They were like, ‘We just put a freshman who hasn’t done anything in our lineup on opening day? What’s going on here?’” Then Frelick went three for three, with a home run and a stolen base. “The guys were like, ‘OK, here we go,’” Gambino said.

A couple of weeks later, in Lexington, Kentucky, BC was scheduled to play on Ash Wednesday. After waking early to attend Mass (to the surprise of his coach), Frelick joined the team to take batting practice before the game. Then a song came over the speakers. “Sal starts dancing,” Gambino said. “Then everybody starts getting into it. This kid is three weeks into his career, and he’s confident enough to be himself, and the guys are responding to him.” Later, during the game, Sal hit another home run and helped his team beat Kentucky. “I saw his leadership, his confidence, his personality, his ability to have fun,” Gambino said. “And then he goes and wins a game with power and speed.”

Frelick was named second team All-ACC in his freshman year, hitting .367 in thirty-eight games, driving in thirty-two runs, and scoring another thirty himself. His sophomore season was cut short by the pandemic, but in forty-eight games in his junior year he hit .359 with six home runs, seventeen doubles, thirteen steals, and fifty runs scored. Frelick was selected as both first team All-ACC and the conference’s defensive player of the year. Baseball can be something of an overlooked sport at BC, not always getting the same recognition as hockey, football, or basketball, but Frelick was capturing the attention of scouts throughout pro ball.

When draft day arrived in 2021, Frelick’s family, friends, coaches, and even high school teachers and BC professors gathered around the TV at his parents’ house in Lexington to see if he was going to get the call. “It’s nerve-wracking. You don’t know what’s going to happen,” Frelick said. With Gambino’s five-year-old son sitting on his lap, Frelick stared intensely at the television. “I’m sitting on the couch, like, please just someone call my name,” he recalled. Then, with the fifteenth overall pick, the MLB commissioner announced that the Brewers were taking Sal Frelick. Back in Lexington, the room erupted in cheers.

A multi-sport athlete from childhood, Sal Frelick, was a star quarterback at Lexington High School, and was eventually even offered a football scholarship at Boston College. Photo: David Gordon/USA TODAY NETWORK via Imagn Images

Combining elite athleticism and a fierce competitive drive, Sal Frelick went on to become one of the best baseball players in Boston College history. Photo: BC Athletics

Draft day was another one of those unforgettable moments. But it was followed by something a lot less glamorous—the minor leagues.

Pat Murphy, now the manager of the Brewers, met him at spring training when Frelick was starting his minor-league career. At the time Murphy was the Brewers’ bench coach, and Frelick had no idea who he was.

“I told him I was the video guy,” said Murphy, who is known for his cutting, deadpan humor. “He didn’t know who I was or how to take me. I asked him if he had been drafted. He said yeah.”

“Pretty low, right?” Murphy said.

“No, actually pretty high.”

“Wow. What were we thinking? Where are you from?”

“Boston,” Frelick said.

“You’re a Red Sox fan? Who’s your favorite player?”

“Dustin Pedroia.”

“Pedroia sucks,” Murphy said, and walked off.

So began Frelick’s time in the minors, where the goal is always to get out of the minors. Players might just be a step or two away from the big leagues—but even for top prospects, they can be big steps. Frelick remembers the interminable bus rides, bad food, his parents trying to watch him play over the glitchy streaming feeds that make up a lot of minor-league broadcasts. “It’s awful, it’s terrible,” he said about those months. As challenging as that time was, Frelick never wavered in the commitment he’d made to earn his degree from BC despite being drafted after his junior season. He took summer classes and overloaded his final semester, allowing him to graduate in December 2021, half a season into his minor-league career. “My degree was the main reason I went to BC,” he said. “I wanted to use my athleticism to get into a good school to get a degree.”

With that degree earned, he worked his way up a long list of Brewers minor-league teams that only the most dedicated of baseball fans follow closely: the Low-A Carolina Mudcats, the High-A Wisconsin Timber Rattlers, the Double-A Biloxi Shuckers, and then, eventually, Triple-A Nashville, where he finally received the news during that post-game meal that he was being called up to the majors. The day after learning of his promotion to the big leagues, Frelick was in Milwaukee, stepping into the batter’s box for his first major-league at-bat to the cheers of a sold-out crowd. With his father and siblings in the stands (his mother was back home in Massachusetts watching on the television because the family didn’t have time to arrange for a sitter for their dog Geno), he raised the bat above his shoulders. The count stood at a ball and two strikes when Frelick sent a changeup bouncing down the third-base line. He sprinted out of the batter’s box and beat a close throw for the first hit of his career. But his night was only just beginning. Just as he had done to begin his BC career, he went three for three, and added two runs batted in to help the Brewers beat the first-place Atlanta Braves 4–3. No Brewer had ever had that many hits with two RBIs in a debut. Sports Illustrated called his performance “historic.”

Two days later, Frelick launched his first big-league homer. In less than a week, he was making a name for himself as an impact player at the plate and in the field. The Brewers, with Frelick established as an everyday player, finished 2023 with ninety-two victories and won the National League Central. “He’s not about numbers,” said Murphy, who was promoted to manager after the season. “He’s about winning baseball.”

Last season was no different. Frelick was a fixture in the Brewers’ 2024 lineup, helping to win games with both his bat and his glove. He hit .259 and stole 18 bases…and saved one Brewers win with a home-run-robbing catch that Murphy said would go “down in the record books in Brewers’ history.” The Brewers again won the National League Central, this time with ninety-three wins. During the 2024 season, Frelick also fulfilled the dream of nearly every boy who ever grew up in Massachusetts—playing a major-league game at Fenway Park (just with the wrong jersey on). “The first time we played at Fenway, standing in the line for the anthem, I was like, ‘Wow, that’s the Red Sox over there,’” he recalled. “Then the game starts, and you’re trying to beat their faces in.” After the game, Frelick was free to resume his lifelong love of the Red Sox, and one of the team’s legendary dirt dogs. In fact, Murphy even arranged for Frelick to hang out for a bit with none other than Dustin Pedroia, the same player he’d once disparaged to Frelick as a prank. “I mess with him pretty much every second of every day,” said Murphy. “I tell him he’s going to be in graduate school in a couple years because people five-foot-eight and 155 pounds usually don’t last in this league. I love the kid. I’d never tell him that, but I love the kid.”

Frelick continues to live in Boston during the offseason. When he’s not at his place in the city, he’s visiting his parents in Lexington, or taking batting practice at BC. During the season, his parents make more than their share of his games in Milwaukee. “After a game, he’ll stand on the field until I get down there, and he gives me a hug,” said his mother, Patty. “He always does that. I love that part of the game.”

That tenderness is no surprise to Frelick’s coach at BC. When talking about his former player’s major-league success, Mike Gambino wanted to make it clear that Frelick is more than just a good baseball player. “This sounds cliché, this sounds fake,” Gambino said, “but the best way to describe Sal is this—he’s the guy that you want your son to idolize, the guy that you want your daughter to marry, the guy you want up at the plate with the season on the line. And not for nothing, if you’re gonna fight, he’s the guy you want fighting with you. He’s that guy.”

But when describing himself, Frelick just shrugged. “I grew up playing baseball hard,” he said. “I just love running around out there.”

Frelick and I concluded our dugout conversation and he headed to the clubhouse to prepare for the game. A couple of hours later, he walked out onto the diamond for a pregame ceremony to accept his Gold Glove trophy. With the jumbotron airing highlights of his many spectacular catches from the previous season, Frelick beamed as he accepted the award. He walked back to the dugout, handed off the trophy, and replaced his smile with the intense expression familiar to anyone who’s watched him play. The award was nice, but now it was time to go win another game. ◽