Edgar Allan Poe or Jane Austen?

Two Boston College English professors duke it out in a page-turning rumble.

Photo: Lee Pellegrini

BOOKS

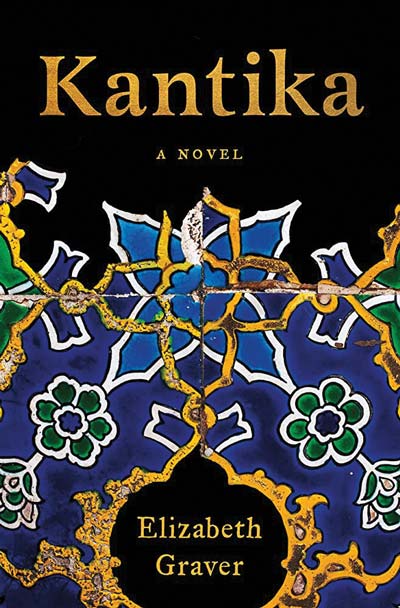

Kantika

BC English Professor Elizabeth Graver writes a stirring family history.

Elizabeth Graver’s latest novel has been decades in the making. When the Boston College English professor was twenty, she interviewed her grandmother, Rebecca, in the hopes of preserving her fascinating, world-crossing story. That was nearly forty years ago, and those interviews about her life and family now form the backbone of Kantika, a fictionalized retelling of Rebecca’s journey from Turkey to Spain to Cuba to New York.

Rebecca, like her real-life counterpart, was born in Turkey, into a family of Sephardic Jews who had, centuries earlier, been forced out of their ancestral home in Spain. The novel charts the course of the lives of Rebecca and other members of the family from the early years of the twentieth century through to the ’50s as they struggle for survival, make heartbreaking decisions about how deeply to assimilate in new countries, and strive to create a sense of home.

Those threads are evident throughout the book. In the aftermath of the fall of the Ottoman Empire, Rebecca’s family flees Turkey in 1925 and moves to its former home country of Spain, only to find that they’re not truly welcome there. Rebecca starts a business as a seamstress, but has to operate under a less Jewish-sounding name. She also discovers, after giving birth to two sons, that her children aren’t granted Spanish citizenship even though they’ve been born in the country. After her first husband dies at the end of the decade, her family sets her up a few years later with a man from Turkey who has American citizenship. The two meet up in Cuba to get to know each other over a whirlwind holiday, and then settle in New York in 1934, where Rebecca’s sons join them and she becomes stepmother to Luna, her new husband’s daughter from his first marriage. It’s a wide-ranging, epic tale of a family moving and resettling across borders in times of global strife, and all of it is based on the real-life saga of Graver’s own family.

While there are abundant Jewish diaspora novels, far more of them tell the story of Ashkenazi Jewish families than of Sephardic ones like Graver’s, in part because there are significantly fewer Sephardic than Ashkenazi Jews in this country. The terms refer to the countries of origin for Jewish immigrants. Ashkenazi Jews come from eastern or central Europe, whereas Sephardic Jews hail from Spain and speak a Judeo-Spanish language called Ladino (kantika is the Ladino word for “song”).

Included throughout the book are photos of the characters’ real-life counterparts, their shifting appearances documenting the family’s efforts to fit in wherever it happened to be living. “When I was using photos of my grandmother,” Graver said, “she can look Turkish, she can look French, she can look Spanish. She changes a lot.”

It’s a shapeshifting performance that also reflects Rebecca’s keen sense of glamour and her own beauty, which becomes a source of conflict with Luna, who emerges as a foil character. Luna, who has cerebral palsy, tends to withdraw in a world that reacts negatively to her appearance. And little wonder, given her family’s acceptance of the 1940s-era conventional wisdom that Luna’s disability necessitates living a constrained life. But Rebecca rejects this notion and patiently works with Luna to help her become more physically independent. Luna at times resents the constant pushing, but also recognizes that her life has vastly improved because of it. The two characters are keen observers of each other’s faults, but as Graver points out, they’re very similar as well. Both are shrewd, motivated survivors, pushing back against a culture that constantly tries to assign them identities that don’t fit. Their relationship ultimately forms the emotional heart of the book—a story about mothers and daughters connecting in the midst of grief, migration, and change, and one that, unfortunately, remains powerfully resonant today as humans continue to be forced to leave home for safer lands.

"It is a historical novel, but I’m always in implicit conversation with where we are now,” Graver said. “These questions of migration and identity and recompense for the past, and why countries welcome people, and why they don’t, and what are the stated reasons and what are the real reasons, are just urgent and compelling.”