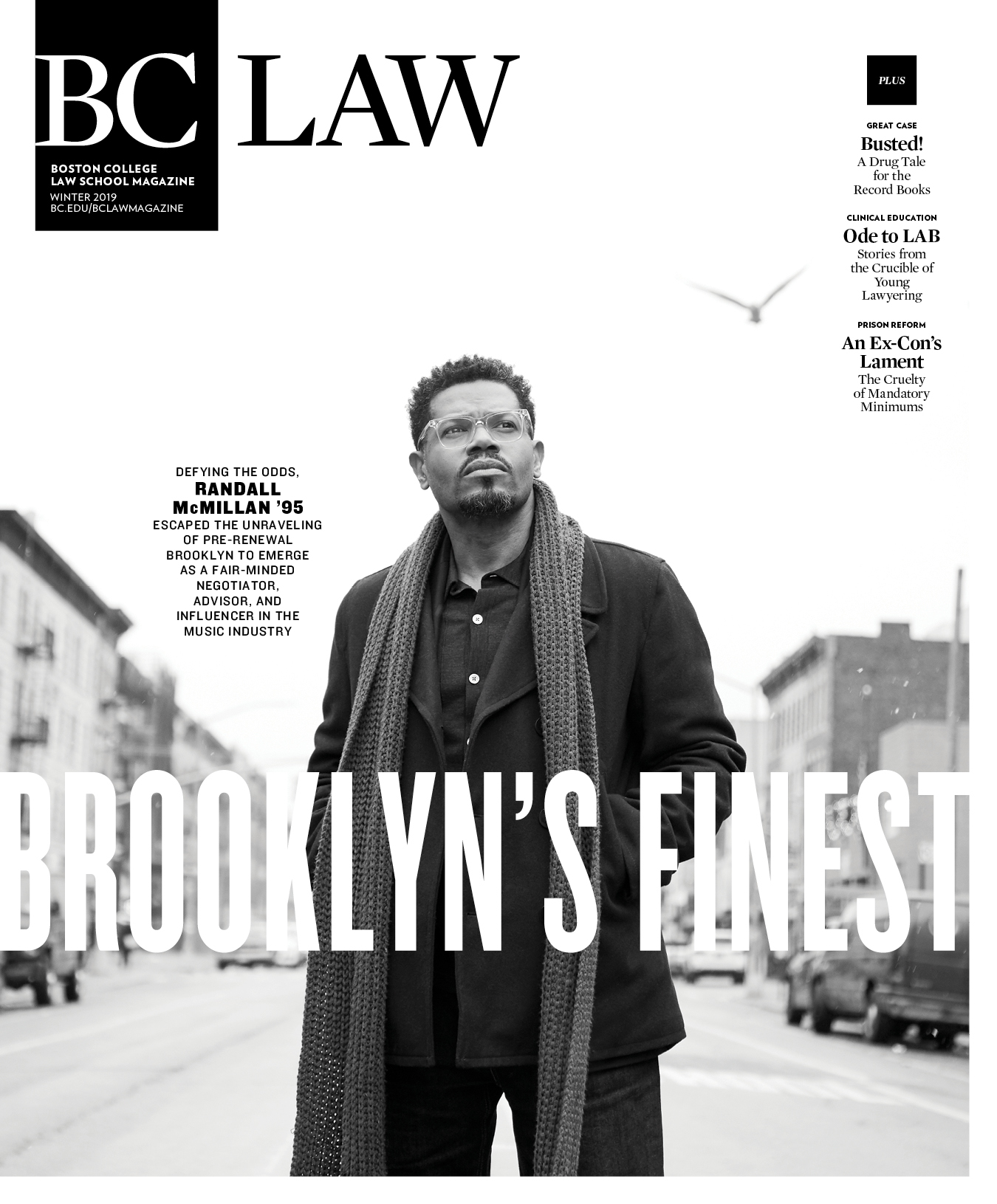

The man whom Randall McMillan has become—husband, father, and a music business heavyweight so expert that an icon of the industry calls him “one of the finest lawyers” in the trade—would seem an alien life form to the boy named Randy, who lived out his childhood in a world coming apart at the seams. It’s easy to forgive McMillan for not immediately diving into that past. There’s plenty else to talk about. Like the fact that Broadcast Music, Inc., better known as BMI, tapped McMillan to become its first Vice President of Business Affairs of Creative and Licensing in 2018.

Now nearly a quarter century into his legal career, McMillan sits thirty stories above Lower Manhattan inside the glass-paneled offices of a global leader in music rights licensing. He is forty-eight years old, but his résumé reads like a guy well past retirement age. He spent a decade at Universal Music Group, the world’s largest record label in terms of market share, where he was responsible for advising executives in the creative, financial, marketing, and production aspects of the business concerning the legal affairs of Def Jam Records, Island Records, and Roc-A-Fella Records, among others.

The BMI job is McMillan’s first with a performance rights organization. In that capacity, BMI serves as the bridge between songwriters and the businesses and organizations that want to play their music. BMI’s core function is to make sure that the people who write, compose, and publish music receive payment whenever their piece is broadcast or performed for public consumption. McMillan synopsizes: “I’m an advocate for creative content.”

Most recently, McMillan served as East Coast Senior Counsel for Artists and Events at Pandora. He has drafted, negotiated, and closed agreements worth tens of millions of dollars involving some of the best-known music brands and many of the most recognizable artists of our time, such as Jay-Z, Rihanna, Lil Wayne, Kanye West, Bruce Hornsby, Natalie Imbruglia, John Pizzarelli, Mariah Carey, and LL Cool J.

“What’s special about Randy is, he’s mastered the corporate side of pinpointing exactly what goals a company wants to achieve, but he also understands we’re the music business,” says global management consultant and attorney Ron Sweeney, the aforementioned icon whose star-studded client list features artists from James Brown to the late Eazy-E, and from Young Money to Lil Wayne. “That means you’re sometimes dealing with people who lack a lot of education, or have huge egos, or both. Randy can look behind somebody’s eyeballs, get inside their head, and figure out what’s most important to them. I know this because I’ve been on the opposite side of the negotiating table from him. He sees all sides of the equation. He can relate to every personal and professional dynamic.”

McMillan isn’t the kind who advertises his own bona fides. He is measured, calm, and coolly unembellished. But after the better part of an hour’s worth of reflection inside BMI’s 7 World Trade Center headquarters, he hits upon a notion he had never considered before. About the paradoxes that shaped who he was as that boy, Randy, and who he is now.

“I think the sense of objectivity [Ron seems to be talking about] might have its roots in my exposure to and interest in music during some turbulent times as a kid,” he says. “Transitioning into my higher education in an Ivy League environment, which was the antithesis of where I lived the rest of the year … those types of paradoxes may have formed the basis for the open-mindedness in my approach to negotiation. That’s funny—I’d really never thought about it in quite that way until just now.”

Fully comprehending the layers of McMillan’s epiphany requires some understanding of the boy, and his boyhood.

“Hip hop helped me feel connected to what was happening in the streets that was positive, as opposed to what was dangerous. It made me feel like I was part of my environment, yet connected with the things that were blossoming, not dying.” —Randall McMillan

PAST IMPERFECT

Born in 1970, McMillan grew up in Brooklyn’s Crown Heights neighborhood. At that time, roughly 460,000 of the borough’s residents were foreign-born. After the Brooklyn Navy Yards closed in 1966, sharp economic decline hit the area (compounded by severe city-wide fiscal deterioration), and Brooklyn suffered a middle class exodus. A rich melting pot, the borough lost more than 300,000 residents throughout the 1970s, including affluent African American families, who left places like Sunset Park and Bedford-Stuyvesant for Queens. Those who had remained watched Brooklyn fade into a landscape of burned-out cars, drug paraphernalia, and boarded-up brownstones.

McMillan was raised primarily by his grandmother from the age of two after his father was shot and killed, and while his mother worked multiple jobs. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, New York City endured a catastrophic rise in crime rates, gang violence, and mob activity. Annual murders across the five boroughs topped 1,800 nine times in the ’70s. That figure ballooned over 2,000 six times during the ’80s with the onset of the crack epidemic which, in turn, fueled an explosion of gun crime and gang-related incidents, especially in Brooklyn.

By the time McMillan was a high school sophomore in 1986, so many teenagers had perished that celebrated community organizer Luis Garden Acosta called North Brooklyn, where McMillan attended high school, “the killing fields.” Randy turned to music as a refuge from the asphalt carnage around him. Having entered his teens at the birth of hip hop, he was drawn to the lyrical contortions, bumping beats, and breakneck evolution of the medium, along with its dance, symbols, and styles. Acts like Public Enemy, Run-D.M.C., and the Beastie Boys became McMillan’s chaperones through the “’hood.”

“I found that music was something that could seriously alter my state of being,” says McMillan. “Immersing myself in music could enhance anything I was doing. Hip hop, in particular, because it’s a culture, not just a genre of music. It gave me these avenues for creative expression.

“Obviously, there was a lot of attention in my house centered on my protection,” he continues. “There were many things I wasn’t able to participate in, many places I wasn’t able to go. I felt a little pinned in. Music gave me an outlet. Hip hop helped me feel connected to what was happening in the streets that was positive, as opposed to what was dangerous. It made me feel like I was part of my environment, yet connected with the things that were blossoming, not dying. It let me outside of those artificial borders my grandmother set for me.”

“I explored things like break dancing. Things like graffiti. I used to fill books and books with my own graffiti,” recalls McMillan. “I was active in talent shows and stuff like that in high school, too.” While steeping in rap’s rich rhymes of social protest, McMillan was also an avid fan of British pop—artists with blond, spiked hair and garish makeup.

“I honestly think my eclectic interest in music during those years is why I’m here today,” says McMillan, expanding on his newfound theory. “In the same way I was head-over-heels for Boogie Down Productions’ Criminal-Minded album, which was all about what was going on in the streets of the South Bronx, I was loving Flock of Seagulls and Frankie Goes to Hollywood. One was more present in my environment, but I found the other really rich. I appreciated it, even if I couldn’t readily identify with jackets that had padded shoulders. I respected it and I had an affinity for it as musical content. I reacted to that, and it made me feel good. Objectively, I wasn’t wedded to one or the other. I do think that’s a parallel to when I’m deal-making in the music business.”

THE COST OF DOING BUSINESS

McMillan knew he was going to college for as long as he knew anything. His mother made sure he understood it was non-negotiable. She talked about it all the time. Randy came to understand it as a trajectory he was on.

As he grew up, McMillan realized a college degree could impact his quality of life and day-to-day environment. Yet, he didn’t really know anyone in his family who was a college graduate. And that made his arrival in Ithaca, New York, as a freshman at Cornell University rather fraught.

“The skills I developed at that time weren’t something I was consciously trying to acquire,” explains McMillan. “But adapting, effectively communicating, and negotiating two different worlds—where I was from and where I found myself—became integral to my own survival and success. I learned how to listen more, and identify the crux of what was important to people. Whether it was my professors or classmates, I realized that interfacing that way would allow me to accomplish whatever my own agenda was. That was a key part of navigating a life that involved coexisting within two dramatically different worlds.”

Though the traits McMillan began to internalize were organic, he gradually became deliberate about curating and codifying them into his modus operandi. “If you know your present circumstances aren’t the same as where you’re trying to get to, then you have to look critically at where you want to go, who’s there, what they look like, and what their interests are,” he says. “You have to try to find common denominators, because you’re going to come into contact with these folks and with these environments, and you’re going to have an opportunity, and it might be fleeting. That’s your place in time to draw upon that common ground and hopefully pull yourself closer to where you want to be. If you aren’t intentional about it, you could miss the opportunity.”

Josh Goodman ’95 has seen that perspicacious side of his classmate in law school and the professional world. “In law school, he was definitely quiet,” recalls Goodman, deputy general counsel for the multinational advertising and PR firm, Publicis Groupe, who has engaged McMillan as an outside counsel. “A lot of people in law school are not quiet, but Randy didn’t seek any attention. He was very understated, he took his work seriously, he was always prepared for class, and he always came across as really smart. Nothing’s changed. He’s of those guys who speaks slowly and thoughtfully and gives you full confidence that he knows exactly what he’s doing.”

“Although BMI writes my paycheck, I still respect that the people on the other side are passionate about their positions for some reason. And, I feel like it’s incumbent upon me to understand what those reasons are to effectively find that meeting point between us.” —Randall McMillan

McMillan is acutely aware of having leveraged the advantages born of an education at Cornell and BC Law. He is also disheartened by the disproportionately high percentages of racial minorities who don’t benefit from the opportunities that he enjoyed. This diversity gap in legal education and the profession remains a shortcoming in the field, hamstringing law firms and corporations that could be better served by the unique perspective and skill set a lawyer like McMillan brings to the table. “I’m saddened and disappointed by the recent low enrollment numbers of black students at BC Law,” he says. “We [at BC Law] need to acknowledge our lack of competitiveness and get more creative if we want to compete for these students in a global marketplace.”

As one might expect, McMillan considers versatility and adaptability to be hallmarks of success in the music business, in large part because that’s the nature of the beast.

“It’s an industry that’s very much a bastion of creativity without bounds,” he says. “The realities of the business change so quickly and people’s interests change so quickly. You have to be able to effectively communicate with a CFO who’s got twenty-five years of experience in corporate America, but also be able to speak to a recording artist’s manager—who has a high school diploma and started in the business six months ago—because the artist he manages is suddenly worth tens of millions of dollars. And that manager might be from my old neighborhood, or from a vastly different background in the South, or from a rural community in the Midwest, or may be born and raised on the West Coast. Being able to communicate effectively with all those folks and truly hear them in order to find the middle ground is a skill I couldn’t survive without.”

Not surprisingly, one of McMillan’s favorite classes at BC Law was called Counseling and Negotiating taught by Professor Ruth-Arlene Howe.

“It was probably one of the most practical courses that I took at BC,” he explains. “We spent the bulk of our time interacting with each other with the goal of asking questions and really listening and understanding fully what someone’s interests were, in order to elicit information far beyond what they may have initially proffered. I think that experience helped refine and, in some ways, validate those soft skills that I had developed more out of necessity up to that point. The class showed me their value and how I could best apply them in my chosen profession.”

At Cornell, a modest interest in entertainment law led McMillan to a mentoring program that placed seniors with career-targeted alumni during winter break. He was paired with Kendall Minter, a pioneering black entertainment lawyer in New York City and co-founder of the Entertainment and Sports Lawyers Association. By the end of that week, says McMillan, “I realized: ‘I want to do what he does.’ I kept that connection close throughout law school and afterwards because I knew that space is where I wanted to be.”

McMillan’s assimilation into his new world was essentially complete. But it came with a price. Two of his closest friends throughout high school, a pair of brothers, were struggling back in Brooklyn. But McMillan’s intersections with them had become fewer and farther between.

“There are casualties of the [kind of transformation] I underwent,” he muses. “They were going through difficult experiences that I wasn’t around to connect to. As a result, one of them is in prison now for thirty-eight years. The other is in prison now for twenty-six or twenty-seven years. I remember getting a call once from their mother [when I was in law school] and she was like, ‘It’s been so long since we’ve heard from you,’ and she filled me in on how things had fallen apart for my best friends. She ended the call by saying, ‘You know, I wish you would have stayed in contact with them.’ That was really hard to hear.”

And, perhaps, an unfair burden to lay at the feet of a young man in his early twenties? “I think at that time she was just being a mom,” McMillan says. “I’m a parent of three now, and I couldn’t imagine being in her position. Reflecting on it at this point, I see how there are consequences to surrounding yourself consistently, and maybe exclusively, with people who are where you want to be. Because sometimes, I guess, you inadvertently leave some people behind to move forward.”

LET’S MAKE A DEAL

Back when he worked for record companies, McMillan fulfilled multiple responsibilities with BMG Entertainment’s RCA Records Label, where he stewarded legal matters pertaining to diverse and iconic artists, including Elvis Presley, Duke Ellington, Christina Aguilera, actor John Leguizamo, and the Foo Fighters. On that side of the business, he dealt with recording agreements and renegotiations and advised executives on day-to-day developments in the industry regarding artists’ videos, sponsorships, and endorsement deals.

McMillan also ran his own shop (McMillan Law, PLLC) from 2011 through 2015, directly counseling artists in structuring and negotiating a broad range of commercial transactions. Though he never grabbed lunch with label president Jay-Z while serving as in-house counsel for Roc-A-Fella records, he has many stories from the MTV era and the pre-internet politics of building a musician into a mogul—a time when record companies were basically artists’ only business partner.

McMillan has squeezed inside dozens of cramped conference rooms into which someone wheels an upright piano so a yet-to-be (and perhaps never-to-be) discovered fresh-faced talent can audition. There are many highlights from days like that, but one, in particular, remains vivid enough in his memory to seem like it happened yesterday.

“I remember being in this conference room that would normally hold maybe twenty people, and we had like fifty people wedged into it,” he recalls. “This A&R exec brings in this young girl, short hair, sort of blond. Petite. She stands next to this piano, and he starts playing. She’s clearly nervous and a little intimidated by this mass of people less than ten feet away from her. I can’t remember what he played, but he does a little ditty, and she starts to sing. And everybody started looking at each other.

“There were no microphones,” he continues, “but her voice was so strong that we started to become physically uncomfortable in that space. You could feel the hairs rise up on your forearms and up your back. I’m feeling it again right now just talking about it. You just felt like her voice was hitting your body. Impacting it. It was so powerful. That little, petite thing was Christina Aguilera. I’ve been in that situation a number of times. With some greatartists. But I’ve never physically felt that reaction to a person’s voice, before or since. The idea that it was coming out of something so small—that really struck all of us. It probably lasted all of three minutes, but I’ll never forget it.”

McMillan’s role at BMI is a world away from maneuvering spine-tingling moments like that one into a win-win recording deal, but his job is still about fighting the good fight for songwriters.

Copyrighted music can’t be performed in public without the permission of the affiliated copyright-holder. When seeking permission to publicly perform the copyright-protected work of a songwriter or composer, it’s not necessary to contact that artist directly. Instead, users can seek a license from a music performing rights organization, also known as a PRO, which represents the work of that songwriter or composer. As such, BMI contractually acquires public performance rights from copyright-holders, signs blanket licensing agreements with businesses and organizations seeking access to the music, collects fees from these licensees, and distributes them to the affiliated copyright-holders.

The largest PRO in the US, BMI’s roster includes more than 900,000 songwriters, composers, and publishers, while its music library includes more than 14 million copyrighted works from every corner of the music world. BMI writers have won numerous GRAMMYs, Country Music Association, and American Music awards. They also represent the largest percentage of inductees into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, account for roughly one-half of all of the winners of the coveted Pulitzer Prize in the field of classical music, and have received the most Rhythm & Blues Foundation Pioneer Awards and Downbeat Jazz Poll Awards. Notable affiliates include Lady Gaga, Taylor Swift, Eminem, Maroon 5, Sam Cooke, Dolly Parton, and Shakira. The company operates on a nonprofit basis, returning 90 cents of every dollar brought in from licensing fees to the musical creators and copyright owners it represents.

“This is actually the first entertainment-related job I’ve had, where I haven’t worked for a company that creates something,” says McMillan. “It’s different in that respect, but there’s still a key piece of my job that involves me advising on entering into transactions with creators. It’s a broader role than I’ve had to date, but it draws upon the wisdom and experiences I’ve developed in different roles and in different settings.”

Throughout the 1990s, BMI’s licensing departments expanded their reach beyond partners like bars and restaurants to emergent users like health clubs, banks, shopping malls, and amusement parks. In the mid-1990s, BMI negotiated the first agreement licensing music performed on the internet. New frontiers like ringtones, satellite radio, and music streaming services followed. Thanks to lucrative deals with Netflix and Hulu last year, the company’s fiscal 2017 revenue rocketed to a record $1.13 billion, which marked a third consecutive year of revenue increase for BMI. McMillan plays a key role in strategizing and negotiating such deals as the head of Business Affairs.

“I’m touching on both recorded music as well as other media, but also with a hand in the talent side of the business,” he says. “I’ll weigh in on negotiations that we may be having with multi-platinum recording artists and writers, who may be looking to move from one PRO to another. I’ll weigh in on incoming litigation that may involve someone who we have licensed rights to, who’s being sued by a third party contesting those rights. I’ll weigh in on negotiations that we may have with broadcast television networks, or digital service providers. And, I’ll weigh in on strategies for how we can effectively find middle ground with large media associations.”

There haven’t always been this many moving parts for BMI, which was founded in 1939. Almost every aspect of the music industry has been altered by technology’s rapid and dramatic impact.

“Today, we have a much greater diversity of business partners than we’ve had in the past when it comes to music,” says McMillan. “I may have a transaction one day with a TV network, and the next day, I may have a transaction I’m doing with YouTube. The next day, I may have a transaction that I’m doing with Verizon. I mean: That’s a phone company. A robust connection between that sector and music wasn’t something we could have readily perceived ten or fifteen years ago.”

Still, McMillan feels like he’s calling plays in the same game he started out in. “I’ve been in the middle of engaging with talent for most of my career, and now I’m engaging on behalf of their content with the people in the marketplace who are exploiting that content. In this new role of performing rights, I spend a lot of time trying to really understand where the middle ground is,” he adds. “What’s our motivation, and what are our limitations? What are the motivations of the people on the other side of the table, and what are their limitations? And where is that middle ground that’s mutually comfortable, and mutually uncomfortable. Because although BMI writes my paycheck, I still respect that the people on the other side are passionate about their positions for some reason. I feel like it’s incumbent upon me to understand what those reasons are to find that meeting point between us.”

Yes, Randall McMillan remains in that space where he has long wanted to be. And those same soft skills and that same relatability, born of necessity from a Brooklyn long forgotten by most, still have value.