At a high school baseball showcase more than a decade ago, Boston College head baseball coach Pete Hughes approached an athlete whose skills needed refining, but who oozed enough positivity to compensate for the holes in his game.

“Have you ever considered going to Boston College?” Hughes asked.

“Only my whole life,” Pete Frates replied.

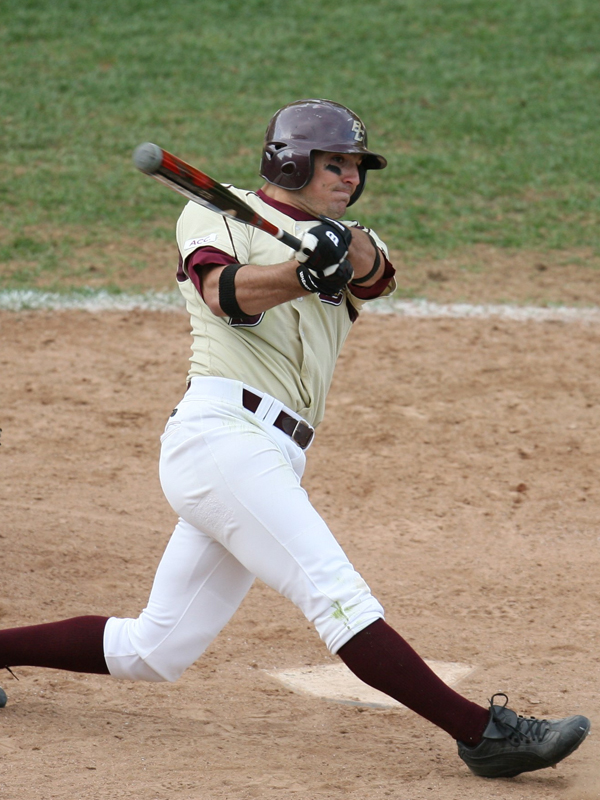

Raised by two Boston College graduates, the Jesuit institution's values — attentiveness, reflection, love — had long been instilled in Frates, and he hoped to join the university's ranks. Still, the three-sport athlete had yet to master his skills on the diamond, and he hadn't considered that he might one day be able to don a maroon and gold baseball uniform — until Hughes asked.

“I thought, even if this kid never plays an inning for me, he's going to make everybody else in that clubhouse better because of who he is,” Hughes said.

As he fights for his life, Frates' impact has spread well beyond that clubhouse.

On March 13, 2012, nearly five years after his playing days ended at Boston College, Frates was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also known as Lou Gehrig's disease. The unlikely recruit turned powerful outfielder who tied for the team lead in home runs in his junior and senior seasons was about to embark on his life's most harrowing journey, but the first words he uttered to his parents after the diagnosis were selfless, not selfish: “What an opportunity we have to change the world.”

“After being told you have two to five years to live, who would say that?” said John Frates, Pete's father. “Unless you have experienced competition at the highest levels, overcome obstacles, worked so hard to make yourself a better human, a better athlete, a better person.”

At Boston College, Frates, the team captain, kept spirits high during 6 a.m. practices and was the first to pick up trash before leaving the dugout. And while Atlantic Coast Conference rivals in the Southeast took grounders and shagged infield flies in January, the Eagles shoveled their way to practice, usually not seeing a fly ball until mid-February.

“You deal with adversity and you're better because of it,” said Tom Bourdon, who played baseball at Boston College while Frates was the director of baseball operations, a job Frates took less than a month after his diagnosis. “We're playing with 2 inches of snow on the ground. It's freezing cold. You have every excuse in the book, but Pete Frates was a no excuse guy.”

After the doctor's words changed his life, Frates embraced his new job as director of baseball operations. He maintained his role spearheading Eagles Career Night, which was designed to help student-athletes find a path after baseball. He also adopted a new team: the ALS community. He hoped to become the face of the disease, raising awareness and funds to find a cure.

The Eagles traveled to Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University for Frates' first road game in his new role. Hughes, his former coach, was at the helm of the Hokie program after leaving Boston College in 2006. Frates threw out the ceremonial first pitch, and the words he delivered to the Boston College players before they took the field have stuck.

“It was the first real conversation he had with us about the diagnosis,” Bourdon said. “He talked about how important teammates are throughout your life. He said his BC teammates are his brothers, and now he has hundreds to lean on while he's going through this.”

As Frates' physical abilities diminished, those brothers came to his aid. They helped tie his shoes, zip his jacket and get food to his mouth. Still, for three years, he traveled with the team. By Bourdon's senior year, Frates had lost his ability to walk. His presence was an invaluable example for the young men he interacted with. “He's done more for these boys and our program than our program has ever done for him,” Boston College baseball head coach Mike Gambino said.

Despite the praise and platitudes, life is not easy. Frates calls his disease “The Beast” and himself “The Bionic Man.” He uses a wheelchair and lives without the use of his extremities, but remains fully cognizant of the world around him. Machines and full-time care specialists now keep him alive. With the 24-hour nursing, a medical supply closet stocked with syringes and oxygen, the Frates home in Beverly, Massachusetts, approximates an intensive care unit.

Even after losing his ability to speak, the former communications major has inspired others. In July 2014, Frates began an initiative that would become his largest impact on the ALS community. A campaign started by three others became a phenomenon when it reached Frates and his home city: Boston area athletes, teams and celebrities began pouring buckets of ice water over their heads in honor of Pete Frates.

After “Team Frate Train” embarked on the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge, it swept the nation. The likes of LeBron James, Oprah Winfrey and Bill Gates posted videos, and the initiative took social media by storm, raising over $220 million for the ALS Association in the summer of 2014 alone.

“When he was diagnosed, he immediately made up his mind to go change the world of ALS,” former Eagle teammate Ryne Reynoso said. “And he's done it.”