On January 5, 1970, Arthur J. Doyle, BC’s director of admissions, wrote a letter to Deborah Imri, "the first coed admitted to our School of Arts and Sciences."

Photo: Lee Pellegrini

Celebrating 50 Years of Coeducation

As BC marks half a century of coeducation, we look back at the women who made it happen.

On January 5, 1970, Arthur J. Doyle, BC’s director of admissions, wrote a letter to Deborah Imri of Rowayton, Connecticut. It did not read like most college acceptance letters. "You are probably familiar with the deeds of your Old Testament namesake who helped set the Israelites free," it began. "And although your triumph may not be as heroic as hers, you will nevertheless go down in history—the history of Boston College, at least—as the first coed admitted to our School of Arts and Sciences."

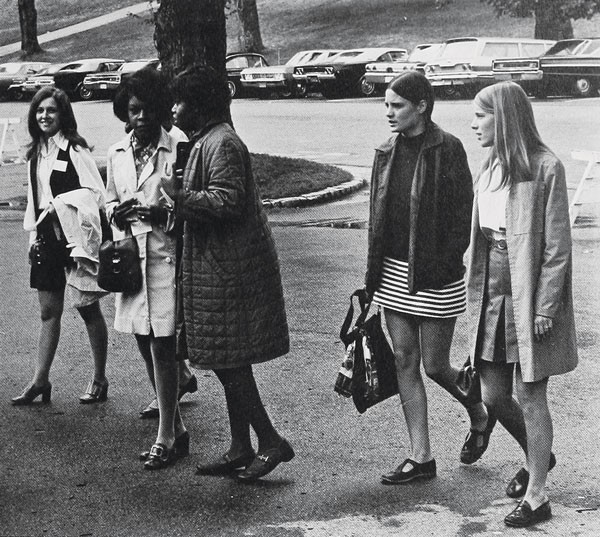

That fall, Imri was just one of the 247 women who arrived on campus as members of the first-ever coed College of Arts and Sciences class. Seventeen women were also admitted to the School of Management. Women for decades had been admitted to the Education and Nursing schools, and had been allowed to earn graduate degrees, but it wasn’t until the 1970–71 school year that BC became fully coeducational.

"I was so excited because I got it in," recalled Imri, who now goes by the last name Tully. She had attended a coed high school and didn’t give much thought at the time to being among the first women to enter A&S, which was renamed the Robert J. Morrissey College of Arts and Sciences in 2015. "But," she said recently, "I did wonder if they realized I was a Protestant."

The women of the Class of 1974 found Boston College welcoming, if not completely prepared for how their presence would reshape the campus. In Fitzpatrick Hall—which had previously housed the school’s football team— women jostled for access to the only mirror in what had been the men’s bathroom. Kathleen O’Donnell, a history major who lived in Fitzpatrick, recently recounted the confusion of Saturday nights, when women would come knocking on the dorm’s doors, expecting to meet the BC football players.

O’Donnell also recalled dribbling basketballs across campus to the Roberts Center to protest the lack of athletic facilities for women, and demanding that the health center, unused to treating a large number of women, provide better care. "But the issues of coming into a college that was adjusting to being coed were minor compared to the fact that you had friends who were getting their number pulled in the draft lottery," she said.

For Theresa Hilaire, now Hogg, a political science major who transferred to Boston College as part of the school’s Black Talent program, being among BC’s debut fully coeducational cohort was a parade of firsts. Hogg—who lived with her then-husband, Stafford Hilaire, as head residents in the dorms when their daughter, Mika, was born—recently recalled being the first woman to ask to cover the men’s basketball team for a school publication, and taking part in a new push to get BC to provide childcare. "Sometimes they looked at me like I was crazy," Hogg said of the administration in the early 1970s. "Everything was new to them, but they were accepting."

However radical coeducation may have felt to some at BC, to others it was merely a natural extension of the broader cultural forces shaping campuses across the nation. "It seemed so normal and natural to me, part of the evolution of the time," said Kathleen McGillycuddy, a founding member of the Council for Women of Boston College, and the first woman to chair BC’s Board of Trustees. "It was a continuation of their focus on mission: women and men for others. The realization of that mission just wouldn’t have been possible without equality across genders." Fifty years on, as Boston College celebrates its golden anniversary of going officially coeducational, this is the story of the women who made it happen.

Women were already allowed to take electives in the College of Arts and Sciences. So why couldn’t they earn a BA from the school?

School of Education sophomore Virginia Meany spent hours in the Eagles Nest at McElroy Commons in October 1966. She was not alone. If you had something to sell or something to say on campus that fall, you did so at the 800-seat snack bar that was Boston College’s de facto public square. This was the place to buy bus tickets to the BC-UMass football game, order your yearbook, and vote for homecoming queen. It was the place to read, play cards, practice French, and flirt. By the end of each day, the tables were littered with empty coffee cups, overflowing ashtrays, and discarded newspapers.

For Meany ’69, MA’77, and her two classmates Martha Ann Brazier and Katherine Mongeau ’69, the Eagles Nest was also the place to persuade. There were lots of petitions on campus in 1966: That year, students were asked to support a new lounge in Lyons Hall and institutional recognition of the activist group Students for a Democratic Society, and to oppose a tuition hike and the Vietnam War. But the petition that the three sophomores from the School of Education had drafted had the potential to be the most consequential for the campus. It urged Boston College to admit women into the all-male College of Arts and Sciences.

Marty, as Brazier was known to her friends, brought the idea for the petition to her two classmates. Meany was eager to sign on to the campaign. Though she had been admitted to the School of Education, she was beginning to realize she didn’t want to be a teacher. And she was already taking French electives in the College of Arts and Sciences. Why couldn’t she simply enroll in A&S? The three friends decided to circulate the petition. They made a good team. Brazier was the outspoken activist. Her father, Gary Brazier, was a professor in BC’s Political Science department and an advocate for student participation in campus politics. Kathy Mongeau, for her part, was the always-organized planner of the group. And Meany, who had been active in the student government at her coed Boston-area high school, was the storyteller. The women’s goal, as she framed it, was born out of respect for the rigor of BC’s liberal arts curriculum and a devotion to the school.

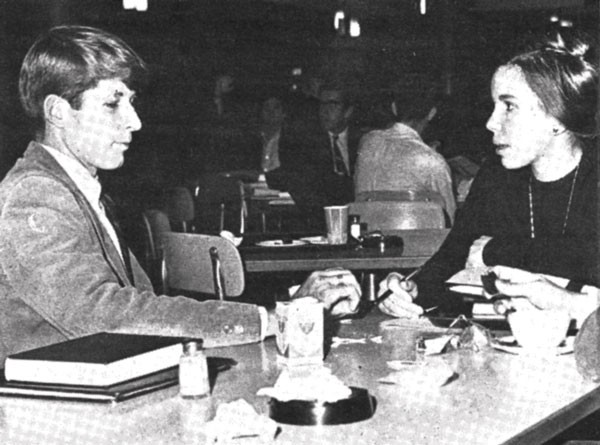

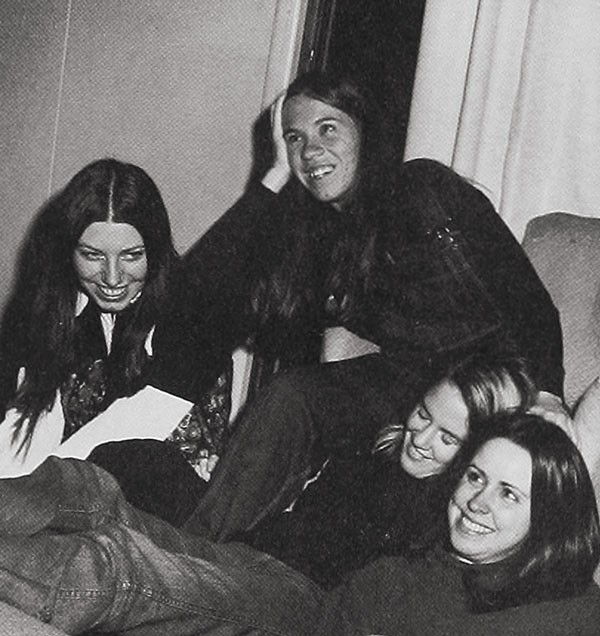

On the afternoon of Monday, October 24, just a few days into the petition drive, Brazier spotted Gus Fabens in the Eagles Nest (their 1966 meeting is pictured here). The young math professor was popular among students, known as an energetic lecturer but a tough grader. His signature would be a good get. At a table in the crowded snack bar, Brazier made her case. She’d already had a lot of practice. All qualified applicants should be admitted to A&S, she told anyone who would listen. Women had been admitted to the School of Nursing since its founding in 1947 and the School of Education since its start in 1952, but both offered bachelor of science degrees. Since women were already allowed to take some electives in A&S, there seemed to be no reason why they shouldn’t be able to earn a bachelor of arts from the school. It was unfair to limit their opportunities in that way, Brazier argued.

Fabens heard Brazier out, but declined to sign the petition. Two days later, though, he changed his mind and added his name to the 850 or so the trio had already collected. Of the students and professors who wouldn’t sign the petition, however, many expressed fears that neither men nor women would thrive in coed classrooms. To counter that argument, Brazier reached back even farther in Boston College’s history: In 1963, six women had graduated from the College of Arts and Sciences.

The smiling faces of Ann Bell, Mary Driscoll, Diane Glennon, Margaret McLaughlin, Elizabeth O’Connell, and Mary Jane Skatoff stood out in the pages of the 1963 Sub Turri. Though the yearbook was filled with photos of the hundreds of women who graduated from the Nursing and Education schools, these six were the only ones pictured alongside the approximately 450 men who graduated that year from the College of Arts and Sciences.

Each of the women had been selected four years earlier by the school administration to be pathbreakers. The first women to enroll in the College of Arts and Sciences as undergraduates, they excelled academically in high school and had grand ambitions for a future career in the sciences. And each of them—along with a seventh accepted student, Caroline O’Hara, who transferred to the Sorbonne after her freshman year—showed the social “adaptability” that Albert Duhamel, then the director of BC’s Honors Program and in charge of recruiting the women, deemed necessary for them to pave the way and succeed in the all-male enclave.

The idea to welcome women into any of the school’s liberal arts programs was raised in the fall of 1958 by Boston College’s new president, Michael P. Walsh, SJ. The plan was to admit women to the School of Education—but, once at BC, they would be allowed to enroll in A&S via the Honors Program and be given the freedom to follow any curriculum they wished, and not be required to take education classes or practice teaching. From the start, Walsh’s proposal was a source of controversy within the administration. Charles F. Donovan, SJ, the dean of the School of Education, worried that the policy could strip the teaching school of its most promising students. He was also concerned, as he wrote in a letter to Walsh, that the whole thing represented “a legal fiction, to cover A&S going co-ed.” Although Walsh didn’t acknowledge it directly, this did seem to be his intent. After six months of negotiations, a détente was reached, and the plan went forward. The seven women were admitted to the School of Education but were then permitted to enroll in the College of Arts and Sciences through the Honors Program.

Before the “vestal virgins”—as the group came to be known—arrived on campus in the fall of 1959, it was unclear how they would be welcomed. When news of the possibility of coeducation in A&S broke in The Heights, in March 1959, reaction was mixed. One senior opined that "any tradition which excludes excellence is detrimental." He advocated for the inclusion of women students in the "spirit of competition…which has always been a part of the Jesuit tradition." He was loudly countered by those who felt, as another senior put it, that "tradition is not always old fashioned; sometimes it is based on practicality." This student thought there were already enough "distractions" on campus. Then there was the sophomore who called coeducation "a dangerous move. This 'equal rights' is being pushed too far."

Indeed, for those who questioned the place of women in the traditionally male bastion of academia, 1959 was an unsettling year in Boston. Just down the road, Harvard Business School—the last all-male graduate school at Harvard University—admitted four women. On BC’s campus, meanwhile, Alice Bourneuf became the first tenured full professor in the College of Arts and Sciences when she joined the Economics department. And though BC’s all-male cheerleading squad was resisting pressure to accept women, female cheerleaders were allowed to participate in the Boston College-Boston University Rally that fall.

Confronted with these changes, and with women students in A&S classrooms, at least one professor lashed out. Elizabeth O'Connell—now Portaro—recalled the harsh reaction of her freshman-year philosophy professor. Reading the roll on the first day of class, the man was startled to see three women’s names on the list. He paused and read their names aloud again. "He asked us to please stand up," Portaro remembered. "He said, 'You are daughters of Eve and don’t know the difference between right and wrong, and I will not have you in my ethics class. Please take your things and leave.'" Shocked and embarrassed, the women left.

As for the A&S male students, they made so little accommodation for the introduction of women into their ranks that they addressed the new arrivals as “mister,” in keeping with campus tradition. In the fall of 1962, when Glennon and Margaret McLaughlin became the first women inducted into the selective Cross & Crown honor society, The Heights article announcing the news was headlined, “Men Picked for Cross & Crown.” Glennon was not amused. In a sarcastic correction sent to the newspaper, she wrote, “I have at last become one of the guys.”

When the initial group of women A&S students arrived at BC in 1959, they believed they would be just the first of many to come. They understood they were part of a pilot program, a first step toward making the College of Arts and Sciences fully coeducational. But no other women followed. Unbeknownst to them, the initiative had been shuttered. The trouble had begun when coverage of the program in The Heights in the spring of 1959 caught the eye of James E. Coleran, SJ.

Coleran, who’d attended Boston College for one year in 1918 before entering the novitiate, was then serving as the Jesuit Provincial of the New England Province, a role that gave him influence over the University. Walsh had not sought Coleran’s permission for the move to admit women, which he saw as a minor tweak to a School of Education curriculum that already allowed students to take some classes in the College of Arts and Sciences. Now Coleran wanted answers. In an exchange of letters with Walsh, Coleran demanded to know whether Boston College’s plan was to go fully coeducational. Walsh confirmed that the women were meant to be trailblazers, adding that his intention had been to petition the Jesuit Order the following year to allow women to be admitted directly to the College of Arts and Sciences.

In making his case to Coleran, Walsh argued that the Catholic Church was losing talented women, especially those who wished to pursue careers in the sciences, to secular schools. Some of these women applied to Boston College’s College of Arts and Sciences each year, despite its prohibition against them, and BC was forced to reject the promising students—and their tuition money. Moreover, Walsh wrote, the church had an obligation to educate the brightest students to challenge “Russian scientific successes.” Women could be a weapon in the Cold War.

But shortly before the start of the 1959–1960 academic year, Walsh’s appeal was rejected. “Since commitments have been made to a certain number of girls this year, you may make such provisions as you wish to carry them out,” Coleran wrote. “But no more girls should be accepted for this course; and, above all, we should discreetly counteract the publicity that appeared this spring.”

And that was that until the fall of 1966, when Brazier, Meany, and Mongeau again made coeducation an issue on campus with their petition. They asked the all-male Arts and Sciences Student Senate to support a resolution in favor of coeducation, and wooed the Women’s Council of the School of Education—both voted in support of the idea. They fundraised and met with alumni on the South Shore of Massachusetts. And they campaigned to convince A&S faculty members of the value of coeducation. English Professor Albert Duhamel, the former Honors Program director who had handpicked the first women to graduate from A&S, was outspoken in his support. “In the four years I supervised these girls I saw no reason why their numbers could not be increased,” Duhamel told The Heights, explaining that the pilot was “unsuccessful only to the extent it was not continued.”

An informal poll of more than 600 A&S students found that 53 percent strongly supported coeducation at BC while only 15 percent expressed strong opposition. On December 5, 1966, the issue came up in a meeting of A&S department heads. Coeducation had not been on the agenda, but Professor John L. Mahoney, chairman of the English department, proposed an informal vote. After the meeting, Mahoney reported to The Heights that “a vast majority of the chairmen are also in favor of the admission of women to A&S.”

“ This anniversary is an important opportunity for reflection on what the institution was then and what it has become now. ”

The next day, Meany, Brazier, and Mongeau delivered their petition, signed by 1,151 people, to President Walsh. It was Walsh who’d led the 1959 effort to enroll women to A&S, and he’d never given up on the idea. Now, with the three advocates in front of him, the president expressed tentative support for their cause, but was neither encouraging nor optimistic about short-term change. He knew the futility of acting without the approval of the Jesuit Provincial, which experience had taught him not to take for granted. He also understood that going coed would require both time and money. Boston College was in the midst of a decade-long transformation from a commuter school that primarily served students from the Boston region to a residential one that drew students from across the country. Before women could be admitted to A&S, Walsh told Meany, Brazier, and Mongeau, the school would need to construct women’s dormitories, an undertaking he believed would take four years or more.

Brazier pledged to fundraise for the buildings—she hoped that Rose and Jacqueline Kennedy, with their strong ties to the Boston Irish Catholic community, might donate—but bit by bit, the objections began to weigh on the young women. They continued to advocate for coeducation, even winning an audience with the Archbishop of Boston, but their belief that they could force the change began to waver. "That is interesting, young ladies," Meany recalled hearing over and over, "but why are you talking to us about something that’s probably not going to happen?" On campus, meanwhile, a backlash to coeducation began to emerge. There were those who argued that men were better alumni donors than women. Others suggested that the school should instead establish a separate college of liberal arts for women. And some wondered if admitting more women would mean accepting fewer men—a particularly fraught discussion in the midst of the Vietnam War, when a college admission meant a draft deferral.

Facing these headwinds as their sophomore year wound down, Meany, Brazier, and Mongeau decided to abandon the movement. “It was not going to happen,” Meany said recently. “We had done the most we could do at that particular point in time.”

The trio of sophomores may have at last been worn down by the resistance to change, but their efforts in 1966 and 1967 had made more of a difference than they’d realized. They thought they’d failed but their slow progress started accelerating quickly as the decade drew to a close.

By the fall of 1968, some women who’d been admitted to the School of Education were allowed to enroll in the College of Arts and Sciences through the Honors Program, as the first six A&S alumnae had been in 1959. By that time, President W. Seavey Joyce, SJ, had taken over from Walsh, and in announcing this revived program—which coincided with a change in governance at the school that gave laypeople more of a voice—the administration was careful to say that it was not a precursor to full coeducation. But many saw it as such. There was little surprise, then, when the University Academic Senate voted in March 1969 to admit women to all colleges starting in the fall of 1970. The news merited three sentences in the next issue of The Heights, under the headline “Yes on Girls.”

It was only a few short months after Meany, Brazier, and Mongeau left BC that Arthur J. Doyle’s letter welcomed Deborah Imri as the “first coed admitted to our School of Arts and Sciences.” Those who’d come before her were enrolled “under special circumstances,” he wrote. “In your case the circumstances are not special, you are.” When the Class of 1974—BC’s first that was fully coeducational—arrived on campus in the fall of 1970, the question of whether women belonged in A&S was a forgotten one. There were other things to debate. The Vietnam War, civil rights, and tuition increases dominated discussions in the Eagles Nest. By the time the class graduated, another major development was in motion. In March 1974, Boston College announced the acquisition of the all-women Newton College of the Sacred Heart. That fall, the college’s 900 students joined the BC student body. Women undergraduates suddenly outnumbered men undergraduates, 5,065 to 4,779, as they do to this day.

In the fifty years since then, women have thrived at Boston College. By 2005, in fact, the University’s living alumni base had become majority female. “This anniversary is an important opportunity for reflection on what the institution was then and what it has become now,” said McGillycuddy, the BC trustee, herself a 1971 graduate of Newton College of the Sacred Heart. “It started fifty years ago, but it’s not finished yet—it’s a work in progress.”

From a distance of more than five decades, Virginia Meany looked back with pride on the part that she and her friends played in that progress. (Katherine Mongeau Kelly and Martha-Ann Brazier, who went by Annie Luther later in her life, have both passed away.) “We had something to say and wanted to fight for it,” Meany recalled. Even when the women decided to end the campaign, she said, they were proud of the fact they had made coeducation such an issue that the school had to respond. Meany returned to Boston College’s Carroll School of Management to earn her MBA, and built a successful career in finance. When she finally retired a couple of years ago, her children unearthed the old articles from The Heights about the petition effort. “They looked at them and said, ‘Wow, you did that!’”

April White, whose historical narratives have appeared in Smithsonian Magazine, the Washington Post, and the Atavist Magazine, is writing a book on the history of divorce in the United States.

print

print mail

mail