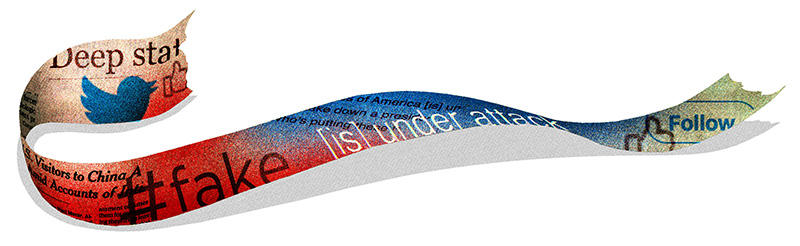

Illustration: Brian Stauffer

Welcome to Post-Truth America

In March 4, 2020, a Wednesday of no particular significance, the president of the United States told seventy-three lies. The day before that, he lied forty times. As of April 3, through 1,170 days in office, Donald Trump had made a total of eighteen thousand demonstrably false or misleading claims. All of this is according to the Washington Post Fact Checker, one of several outlets dedicated to analyzing and correcting the exaggerations, misstatements, and flat-out falsehoods of our politicians.

That an elected official plays loose with the truth is hardly shocking—the idea of a lying politician is so commonplace as to be a cliché. What is remarkable, though, is the number of people who, despite incontrovertible evidence to the contrary, don’t seem to think Trump is lying at all. During the COVID-19 pandemic, for instance—when the president has maintained that anyone who wants a virus test can get one (they can’t), suggested that hydroxychloroquine has showed “tremendous promise” in treating the virus (it hasn’t), and said that one day, “like a miracle,” the virus would simply disappear (it didn’t)—an NPR/PBS NewsHour poll showed that 37 percent of Americans, more than a third of the country, said they still had a good amount or great deal of trust in Trump as a source of information about the pandemic.

It’s easy to single out Trump because of the numbing frequency of his false statements, but he is only a symptom of a larger problem that has been building for decades. A willful, generations-long assault on the legitimacy of the press; the rise of partisan media outlets blending opinion and dubious reporting; foreign governments creating and disseminating propaganda in the form of false news stories; and, crucially, the emergence of social media to amplify the range of misinformation, disinformation, and conspiracy theories—all of it has amounted to a sustained and potent attack on the very notion of fact-based evidence and objective truth.

“The reality is that we’re able to create many types of realities because of the communication tools we can now surround ourselves with,” said Michael Serazio, an associate professor in the BC communication department. “We produce information for social networks and tailor it to what we prefer. We live in a filtered bubble. It’s the notion of our ability to cocoon ourselves in news content that won’t cause cognizant dissonance.”

The data clearly support the overwhelming scientific consensus on the threat of climate change and the safety and benefits of vaccinations. There is irrefutable evidence that the Holocaust happened and that a deranged gunman murdered twenty children and six adults at the Sandy Hook Elementary School. Each of these things is true by any historical standard. Yet, to varying degrees, each is viewed with skepticism by large swaths of the American public. Meanwhile, a 2016 Gallup poll found that just 32 percent of Americans had faith that TV, newspapers, and radio were reporting the news “fully, accurately, and fairly.”

So how has it come to this? How have we arrived at a moment when it seems that we disagree not just on what something means but on whether it is even true? What happened to our faith in the media as a trusted arbiter of the truth? Can we ever return to a time when, generally speaking, we agree on what is real, what is not, and who is qualified to decide—and did such a time ever exist?

In many ways, it makes perfect sense that we, as Americans, have formed such a tenuous relationship with the concept of one reality. After all, as a government, as a society, and as a culture, we were built on the idea of multiple opinions and viewpoints. Our tradition of liberal individualism is rooted in the belief that everyone’s experience and opinion is valid. Everyone gets a vote, a voice, and a chance to be heard. So it’s hardly surprising that so many Americans have come to believe that they have a right to their own truth. In fact, expertise and authority are now sometimes viewed with skepticism. “Someone in their basement who has a crazy idea is more trustworthy because he’s more authentic,” Serazio said. “They’re not part of the system. Things that are created professionally are suspicious.”

It’s enough that Sylvia Sellers-García, associate professor of history, has begun to reevaluate her thinking about the nature of truth. In her course Truth-Telling in History, Sellers-García looks at the challenges of relying on primary sources to accurately portray the past, and whether history itself is a form of fictionalizing, even if it’s based on facts. “In the past I was more receptive to the idea that truth is something with many sides,” she said. “I used to think that, whether you’re telling the past or observing the present, it’s going to look different depending on who you are. I don’t discard that notion, but I do feel a renewed call to underscore the importance of evidence at this time. Postmodernists argued that we need to question where the grand truths come from. But I no longer believe that you can take any perspective and say it’s your truth and call it a day. If it’s just your perspective, you need to explain why it’s valid.”

The demonizing in some corners of expertise and authority, and the concurrent it’s-my-truth-ification of so much of American discourse, has helped to create a dangerous vacuum. In other countries, which are trying to navigate the same murky waters as the US, Big Brother—the state—has stepped in to fill the void. “What we see in other parts of the world is government more overtly taking on the role of vetting and shaping information and putting it out as a story,” said Matt Sienkiewicz, chair of the BC communication department, who specializes in global media culture and media theory. “This is done overtly at a policy level.” Government-supported media can be in the public interest, of course—consider such trusted outlets as PBS and NPR—but it can also be used to blatantly twist and shape information via internet troll farms and other online campaigns designed to sow discord and spread misinformation through social media.

There has been more new error propagated by the press in the last ten years than in an [sic] hundred years before...

These words were written by a US president—but not in a tweet. They were jotted by John Adams in the margins of a book, next to a passage in which the French philosopher Condorcet extolled the virtue of the new “free press” and it’s potential to inform the general public.

Our era, then, is hardly the first in which the idea of objective truth has come under fire. In fact, this practice of undercutting the media is at least as old as the country itself. Which is not to say that the press hasn’t at times earned the scorn that it receives.

Adams, for his part, had reason to be cynical. He had been targeted and libeled by partisan pamphlets and broadsheets, just as public figures had been in the two centuries since the invention of moveable type and the proliferation of printing presses had given voice to just about anyone with something to say. The problem persisted throughout the 1800s, into a period of Yellow Journalism that straddled the turn of the twentieth century, when facts and comprehensive reportage were sacrificed in favor of salacious headlines and copy, the better to sell newspapers.

Things started to change with the rise of radio and then television and the resulting consolidation of American newspapers. Suddenly, in the middle part of the 1900s, just a handful of broadcast networks and print publications—boasting robust and powerful news departments—were largely controlling the information consumed by most citizens. “Back in the good old days of network news and large and reputable news organizations, they were the arbiters,” said Gerald Kane, a professor in the Carroll School of Management who also helps Fortune 500 companies develop strategies in response to changes in digital technology. “There was pretty strong public trust in them.”

When Edward R. Murrow described the blitz devastating London, shocked listeners didn’t question what they were hearing. When Walter Cronkite teared up and told America that John F. Kennedy had been shot and killed in Dallas, the public never wondered whether it had truly happened. When Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, under the trusted banner of the Washington Post, broke the Watergate scandal and eventually connected it and the subsequent cover-up to Richard Nixon, the country reluctantly accepted that its president was, in fact, a crook. Any dissent from fringe voices or outlets was more or less considered nonsense. “We used to not receive information from elsewhere,” Sienkiewicz said. “The American media sphere was very hard to penetrate.”

This period of centralized news in America turned out to be relatively brief. The first holes in the news filter were created by cable TV channels that could dedicate an entire day of programming to news—even if there weren’t twenty-four hours worth of news to report. Old controls, such as regulation of the airwaves and fair time given to politicians, were out. The rise of politicized media was in. “If you can’t get more facts, what do you rely on? Opinion,” said Serazio, whose research focuses on political communication and new media. “And more space creates a faster output of opinion.”

Now consider the infinite space of the internet. Today, fact and truth are out there bouncing around cyberspace, competing for attention with all manner of opinions, rumors, and half-baked theories, all of it moving at the speed of fiber optics. Whatever you prefer to believe, a “story” can be found out there confirming it. If ever we needed a universally trusted arbiter of what is true and factual and what is not, now is the time. Yet even as the established media’s credibility is regularly challenged by large portions of the country, including the president, the industry finds itself struggling to stay afloat financially in this digital age, forced to play the old game of competing for eyeballs.

Condorcet’s eighteenth-century theory that, in the uncensored marketplace of ideas, the truth will eventually win out is getting perhaps its most definitive test. Welcome to post-truth America.

So what can we do to reclaim an agreed-upon standard for objective truth? The problem and the solution might be found in the same place: the internet.

Mo Jones-Jang is an assistant professor in the communication department whose research centers on digital information behavior, big data analytics, and media psychology. He recently conducted a study looking at how people on Facebook interact with information that doesn’t necessarily represent their views. There’s a common notion that social media is at the root of our polarization, trapping users in bubbles of affirmation, where they shut out all disagreement and lose touch with the larger discourse. In his study, Jones-Jang actually found the opposite. “People have thousands of friends—and not all are uniformly Democrats or Republicans,” he said. “Actively avoiding friends who disagree requires cognitive energy that most people try to save.” Jones-Jang’s research showed that while people will click primarily on news content that supports their existing political views, and will spend more time with such content, they “aren’t avoiding the posts that aren’t supporting their attitudes.” In other words, the internet does have the power to expose people to new ideas.

“ How have we come to disagree not just on what something means but on whether it is even true? Can we ever again agree on what is real and who is qualified to decide? ”

To harness that power—to begin using the internet as a tool for telling and amplifying truth rather than misinformation and lies—there are roles for everyone from the media to the social media companies to perhaps even higher education.

A particularly helpful development would be for our media organizations to do a better job of keeping such misinformation out of their well-intended news stories in the first place—and that starts with the troublesome issue of false balance in articles. For decades, the traditional media has dedicated itself to the concept of equal time and balance, but that tenet is naive if not downright dangerous in today’s environment. How can you give equal weight to all sides of any issue when some sides have a blatant (if not cynical) disregard for what’s true?

In another of his studies, Jones-Jang focused on news coverage of the anti-vaccination movement. He found that most reporters accurately presented the overwhelming scientific consensus about the safety and benefits of vaccines. Wanting to avoid the appearance of bias, however, the reporters sought to “balance” their stories by giving space to anti-vaccination activists. In the process, they allowed the activists to make dubious claims about the links between vaccines and autism and other conditions. It was classic he said, she said journalism, in which the arguments of the different parties are faithfully presented, and it’s then left to the reader to determine what’s true. Such reporting creates a dangerous false impression that there is actually a substantive debate when, in fact, sometimes there is not. The science on vaccines, for example, is clear and unambiguous: Medical experts overwhelmingly support vaccination. By prizing balance in stories about controversial issues such as vaccinations and climate change, reporters can unintentionally wind up helping to spread misinformation.

Many flawed stories wind up getting shared over social media, of course, and so does a lot of outright propaganda and lies. For this reason, the social media platforms—where so many people get their “news”—also have an important part to play in restoring a collective sense of objective truth. To do that, and to begin harnessing the power of social media to truly inform, the platforms themselves must do a better job of identifying and removing the misleading content that is shared over them. These websites have been notoriously bad at policing the information in their feeds, of course, but Jones-Jang said that is starting to change. For instance, during the current pandemic, when lies and misinformation have literally become a matter of life and death, Twitter and Facebook have started to flag and remove erroneous coronavirus stories that are determined to be dangerous.

CSOM’s Gerald Kane said that when it comes to reestablishing a widely accepted standard for facts and objective truth, there could also be a role for the academy. Our colleges and universities could be the nation’s arbiters of truth, Kane said. “We could use our endowments to push forward as a reputable news source,” he said. “Particularly our journalism schools. Our job is to research and convey knowledge, not to profit. Why not move current events into that sphere and make it part of our mission?”

Another way higher ed could get involved, Kane said, is to document and report the biases of the country’s news outlets, effectively giving each outlet a rating that people could use when considering how credible its reporting is. “Some of my colleagues have done a good job of figuring out how to quantify bias of news sources,” he said. “To the extent we can compare, there’s an ingenious way of identifying underlying bias.”

Then again, said Kane, who also studies emerging technologies, you could eventually remove people from the equation and let the algorithms evolve to the point where they can determine which outlets are trustworthy, the better to filter out the garbage. “Artificial intelligence is going to be a major player in the next ten years,” he said. “We’ll be able to use algorithms to assess a news organization’s bias. That’s the first step.”

Ultimately, the faults is not in our media or technology, but in ourselves. Somewhere in the vast wilds of the internet, the facts we need and want are out there—but we must first want to find them. Even those almighty social media algorithms are just reflections of our own personal biases. So how do you make people care?

The COVID-19 pandemic has upended much of what we thought we knew about our country, and it’s fair to wonder whether the crisis might spark a demand for a return to objective truth and information. A CBS News poll conducted during the pandemic showed that 88 percent of people trusted medical professionals and 82 percent trusted the Centers for Disease Control, compared with just 44 percent who trusted President Trump.

For her part, the noted BC historian Heather Cox Richardson believes that, virus or no, we are nearing a turning point in the war over truth that began long before Trump came onstage. And the outcome might well be determined by whether or not the reasonable majority can look past their personal politics, tap into our shared natural curiosity as human beings, and understand that, deep down, we have an innate need for the truth. “The ideologues will never be convinced that they’re wrong,” Richardson said. “But I hear all the time that ‘We’re all so divided now.’ That has been true for a generation and no one has been paying attention. It’s my view that people are starved for facts.” ◽

Tony Rehegan is a writer based in St. Louis. His writing has appeared in GQ, Popular Mechanics, and ESPN The Magazine.

print

print mail

mail