Andrea Vicini, SJ (Photo: Lee Pellegrini)

The growing threat posed by climate change and environmental pollution has been exhaustively detailed. Often overlooked, though, is how those dangers intersect with social justice. This subject was a major theme at the September conference “Ethical Challenges in Global Public Health: Climate Change, Pollution and the Health of the Poor,” sponsored by the Theology Department and the School of Theology and Ministry, which brought together academics from across the world. I recently sat down with Andrea Vicini, S.J., a conference organizer and the Michael P. Walsh, S.J., Professor of Bioethics, to discuss the moral case for addressing climate change and environmental pollution, and why Boston College—which has launched a new Global Public Health and the Common Good undergraduate minor—is uniquely called to help. Following are highlights from our conversation.

Why we need an improved model for global public health

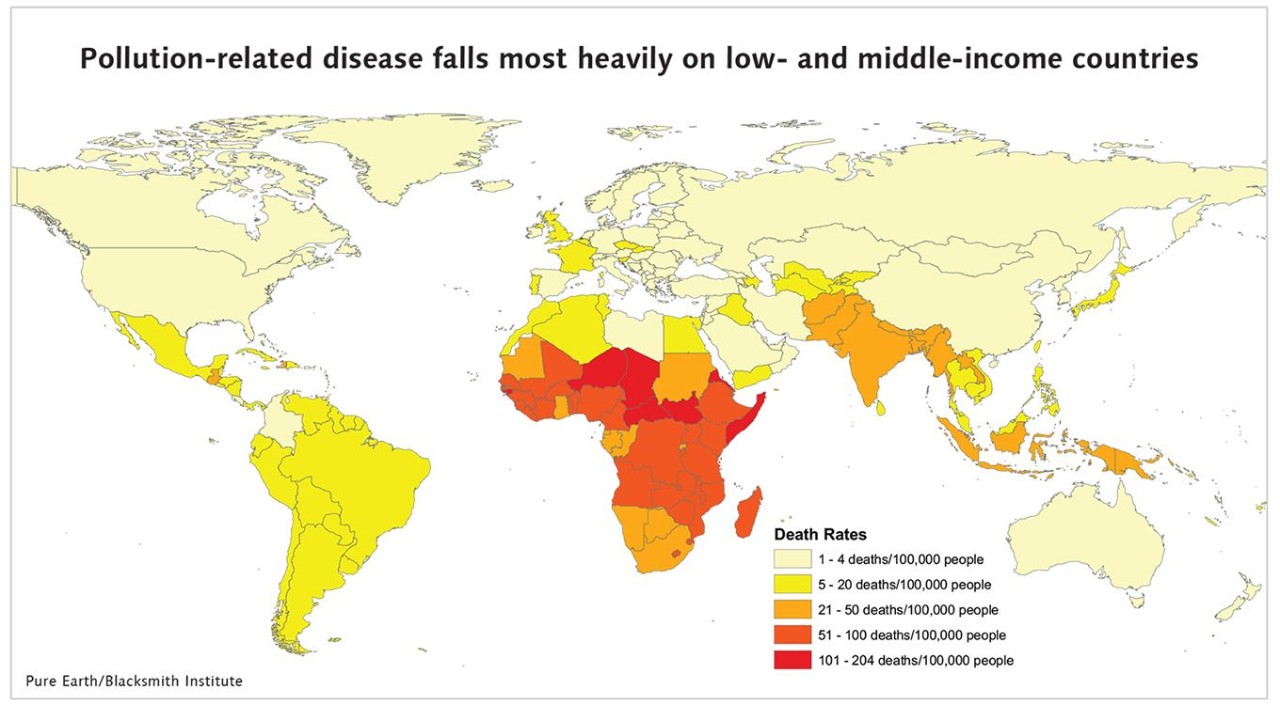

“In the approach to global public health, there has been something missing: a clear commitment to the well-being of the poor and those in need. The belief has been that it’s sufficient to address the issues from a pragmatic point of view—developing solutions. We do need to find solutions: clean energy, reducing waste, decontaminating the planet. But these issues are also part of what it means to promote a just world. The people in the global South are already suffering the consequences of climate change: more days with very high temperatures, more difficulty growing crops, drought. They are not as responsible for it, in terms of the production of CO2 and pollutants, as those in the global North. We might say, ‘It’s their problem, we can protect ourselves.’ Right now, we can. We don’t feel the effects of climate change to the same degree. Yes, there is more variability in our weather, stronger storms, devastating hurricanes, but we can handle all of that for now because we are a developed society. But it’s not just unjust to think of it as their problem and not ours—it’s also a mistake. Everything in health and in the environment is interconnected. For example, with our changing climate, disease vectors like mosquitoes are now in parts of the world where we didn’t have them before, spreading diseases that will become endemic. From a bigger perspective, we need to find ways to promote development of the global South, along with integrated justice—not making them pay for what we caused in terms of pollution and damage to the environment because of the way we live our lives. We need to assume our responsibilities as the global North and reflect on our way of life, and probably we need to change the way in which we live, travel, eat our food—the way in which we consume energy.”

Why Boston College is called to lead on this issue

“Justice in global public health and the environment is a Catholic commitment, it is a Christian commitment, and it is a Jesuit commitment. To use terminology that is part of Catholic social teaching and the official magisterium of the Catholic Church, a preferential option for the poor is what we are committed to promote. And that means we engage with all our creativity, energy, imagination, and resources to create conditions for a greater justice, caring for those who are left out. We are called to work together with those who are in need and not work for them, but to work with them and their own competence and expertise. We have clear declarations and commitments aimed at promoting rights in the area of health and the environment, yet we are in a political and social moment where we see more and more of these rights being undermined. And so as Christians, as Catholics, and as those engaged in Jesuit education, we are called to make a difference and address these issues that are not being addressed sufficiently.”

On Boston College’s new Global Public Health and the Common Good mino

“It was launched at the beginning of this semester. The response has been overwhelming. It was filled in a couple of days. We had students from across the university sign up, with majors in everything from the humanities, economics, and history to biology and pre-med. They saw how this focus on global public health could integrate with the training from their major to promote what is good for humankind and the planet. There are three required courses and three electives. The optional courses cut across disciplinary interest—philosophy, theology, history, law—so the students can learn both the scientific component that’s required in epidemiological studies and these more differentiated interests. The minor is offered through the new Schiller Institute, and we hope it will eventually become a major. First we’ll have the construction of a home for the Schiller Institute, which will be a space to focus on major areas of research and education: health, environment, energy, and data. We’ll have the opportunity to train future generations of leaders, practitioners, social activists, CEOs, and educators with an interdisciplinary approach that combines sciences and humanities. So perhaps the minor aims to shape a way of being in the world, because it seems to me that not only this minor but the entire university aims to train people who will work for the common good, who care for justice—justice not only for themselves and their own, but justice for everyone.”

On the response to the “Ethical Challenges in Global Public Health” conference

We brought together experts from around the world, with disciplines in everything from the sciences, medicine, and the law to social work, theology, and economics. The panel discussions were well attended and energizing, and right up to the end of the day people continued to engage with one another. It was the first occasion for the conference, and some have suggested that this could become an annual event. Perhaps at the beginning of the academic year the Global Public Health and the Common Good minor could organize a conference, keeping us engaged and enriched by reflecting on issues that challenge us in the area of public health and invite us to promote the common good. We’ll see. But for the moment, we are happy that there was such interest and participation.”

John Wolfson | Boston College Magazine

Share your thoughts: bcm@bc.edu