From Nature's Mirror Reality and Symbol in Belgian Landscape, one of three fall exhibitions at BC's McMullen Museum: 'The Servants of Death (Nocturne),' c. 1897, by William Degouve de Nuncques (1867–1935); courtesy of the Hearn Family Trust.

Taking advantage of the expanded gallery space provided by the state-of-the-art venue it has occupied since its reopening in September 2016, the McMullen Museum at Boston College will mount three concurrent exhibitions for the fall season.

Two of the displays will offer a fresh exploration of the genre of landscape painting—one of the most popular art forms—including works from an outstanding private collection rarely on view to the public; the third will introduce the New England audience to one of the first Latin American abstract artists of the twentieth century.

“Nature’s Mirror and New England Sky explore the landscapes of Belgium and New England, respectively, against the backdrop of splendid views of the surrounding land and cityscape visible through the Museum’s glass atrium and from the terrace, encouraging contemplation of the boundaries between observation and artistry and of how landscape both shapes human lives and is shaped by humans," said McMullen Director and Professor of Art History Nancy Netzer. "The Abstract Cabinet continues the McMullen’s commitment to bringing Latin American artists into the art historical canon and exploring their development of a distinct abstract style.”

A Preview Day Celebration for faculty, staff, students, and McMullen Museum members will be held on Sunday, September 17, from noon to 5 p.m., and will feature presentations by exhibition curators. Click here to RSVP by September 15.

The exhibitions will be accompanied by an array of events for its members, BC faculty, staff, students, and alumni, as well as the general public, including Second Saturdays children’s programs, weekly docent tours, members-only Q+A sessions, Museum Current lectures, and the new Into the Collection series of rarely displayed pieces from the Museum’s permanent collection. Most of the events are free and open to the public; details and registration information, as well as other information about hours and tours, can be found on the McMullen Museum of Art website.

Nature’s Mirror: Reality and Symbol in Belgian Landscape

Daley Family Gallery, September 10–December 10, 2017

Art in the region of Belgium and the Netherlands has been known since the Renaissance for innovations in realistic representation of visual appearances and for an extraordinary fluency in symbolism. The development of landscape as an independent genre was fostered by new market forces and artistic concerns in Belgium in the sixteenth century, and landscape emerged as a major focus for nineteenth-century realist and symbolist artists. Nature’s Mirror: Reality and Symbol in Belgian Landscape traces these landmark developments with a rich array of seldom-seen works.

“The McMullen Museum is pleased to present this fresh look at the development of landscape in Belgium and the Lowlands from the late Middle Ages to the early twentieth century,” said Netzer. "Curated by Boston College Professor of Art History Jeffery Howe, in collaboration with other renowned Belgian and American scholars, this exhibition highlights rarely displayed works from one of the world’s finest private collections of Belgian art, assembled by Charles Hack for the Hearn Family Trust."

Illustrating the birth of landscape art, Nature’s Mirror opens with important master prints and drawings from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, by artists including Pieter Bruegel, Hieronymus Cock, Paul Brill, and Roelandt Savery. The next major concentration of works showcases mid-nineteenth-century realists, especially the School of Tervuren. Rare symbolist landscapes from the turn of the century are another highlight, featuring such artists as Fernand Khnopff, William Degouve de Nuncques, George Minne, and Léon Spilliaert.

“In this survey, we see how nature has been used to mirror social, political, spiritual, and psychological factors from the very beginning,” said Howe.

“Now one of the most popular of art forms, landscape painting is rooted in the rise of humanism and scientific exploration in the Renaissance,” he explained. “Liberated from a secondary role as background to religious or mythological scenes, landscape emerged as a new realm of spiritual discovery and enchantment.

“Long seen as a kind of revelation or text, nature now was explored for its own interest. Shifting trends in economics, religion, and market forces led artists to specialize in this genre, and it became a powerful vehicle for personal reflection.” For a variety of reasons, these developments were centered in Belgium and the Lowlands. Science and psychology combined in the nineteenth century to encourage new interpretations. The spiritual dimension returned in romantic and symbolist art, even as concepts of science expanded, mirroring psychological concerns and modernist realities, Howe added.

Displaying more than 120 works—most from the leading private collection of Belgian art in America, the Hearn Family Trust —Nature’s Mirror examines the wealth of artistic expression that bloomed in the regions of Belgium in an unprecedented fashion. Other lenders include the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design; Boston College’s John J. Burns Library; and numerous private collections. Organized by the McMullen Museum, Nature’s Mirror has been underwritten by Boston College with major support from the Patrons of the McMullen Museum and Mary Ann and Vincent Q. Giffuni.

Over the past forty years Charles Hack has built the premier assemblage of Belgian art in North America for the Hearn Family Trust—one of the world’s great private collections. It includes old master prints, many nineteenth-century paintings from the realist School of Tervuren, and outstanding Belgian symbolist works. Hack’s interest in Belgian art was sparked by pioneering art dealer Barry Friedman, who began showing it in his New York gallery in the 1970s, and brought Hack and Howe together given their shared passion for Belgian art. Many individual works in the collection have been loaned to exhibitions at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and major museums in Brussels, Paris, London, and Toronto, but there has never been a broad exhibition showcasing his art prior to the McMullen Museum exhibition, which was proposed by Howe.

Nature’s Mirror is accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue, edited by Howe, with essays by American and Belgian specialists Anne Adriaens-Pannier, Albert Alhadeff, Alison Hokanson, Howe, Catherine Labio, and Dominique Marechal. They examine artists such as Fernand Khnopff, Henri De Braekeleer, and Léon Spilliaert within the regional contexts that influenced them, the transition of Belgian realism to symbolism, George Minne’s poetic illustrations, and themes of industrialization and labor. Nature’s Mirror presents more than 120 paintings, prints, and drawings in chronological order, from the Renaissance through the First World War, illuminating the evolution of Belgian art in this fruitful period.

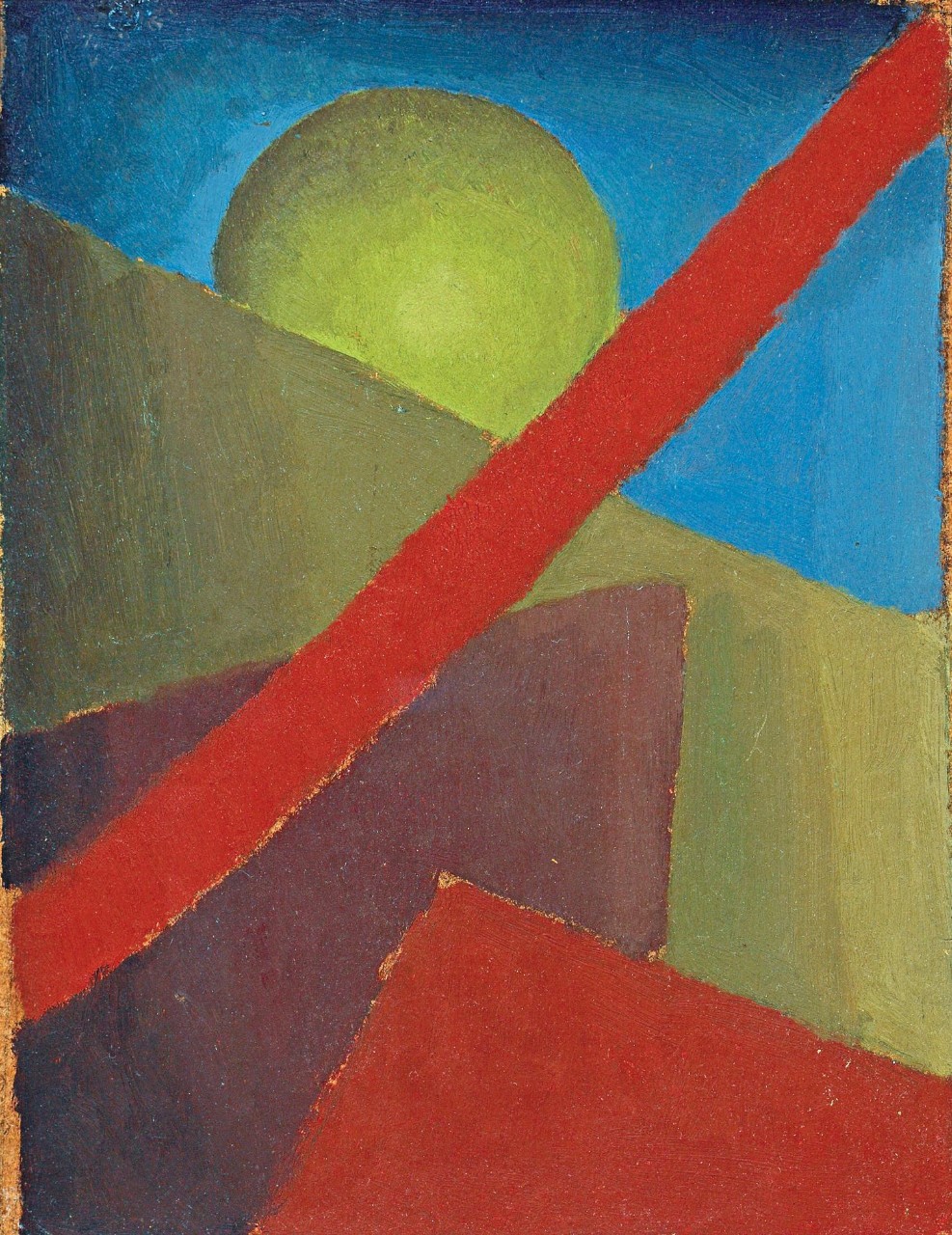

Esteban Lisa: The Abstract Cabinet

Monan Gallery, September 16–December 10, 2017

The Abstract Cabinet features paintings by Spanish-Argentinian Esteban Lisa (1895–1983), a pioneering artist, along with Uruguayan artist Joaquín Torres García, of Latin American abstraction. The McMullen exhibition marks the first showing of the artist’s work in New England.

“An esteemed art educator and writer, Esteban Lisa was an influential figure in Buenos Aires’s cultural life during the middle of the last century,” said Netzer. “His own paintings, however, remained largely unknown until after his death in 1983. As part of its ongoing Latin American initiative, the McMullen Museum is proud to introduce this seminal, lesser-known artist to New England in his first exhibition in this region. The McMullen thanks the Fundación Juan March for sharing their exhibition and Elizabeth Thompson Goizueta [of Boston College] for adapting and amplifying it for the McMullen’s audience.”

Esteban Lisa was born in a village outside Toledo, immigrated to Buenos Aires at age fifteen, and trained at the National School of the Arts and Crafts, which in 1925 certified him to teach painting and drawing. He worked by day at the postal office and instructed intellectuals and artists in the evening. Upon his 1955 retirement, Lisa founded “The Four Dimensions” School of Modern Art in Buenos Aires, where he taught until 1980. Embracing Kant, Einstein, and Picasso (and publishing a manifesto on them in 1956), Lisa believed that abstract art informed by philosophy, science, aesthetics, music, and ethics could provide a clearer understanding of his theories. Specifically, he promoted his theory of “cosmovisión”—a blend of spiritual enlightenment, philosophy of science, and creativity.

Initially influenced by European modernists, Lisa saw his works as engaged with those of Miró, Picasso, Klee, Mondrian, and Kandinsky. After Picasso’s exhibition in Buenos Aires and Torres García’s return to Latin America, both in 1934, Lisa’s paintings change; their synthesis of geometry and symbolism reveal those artists’ imprints. Lisa joined Torres García in embracing a new consciousness in Latin America, imbuing geometric art with a spiritual dimension. Wedding his theory of abstract art to philosophy and science, Lisa strove to spread this utopian vision in Latin America through writings and lectures.

“The Abstract Cabinet features paintings of this pioneer of Latin American abstraction,” said curator Elizabeth Thompson Goizueta, who teaches in BC’s Department of Romance Languages and Literatures. “Lisa’s works, painted on cardboard and scraps of paper, reveal in small scale his theories on the cosmos and the dialectic among aesthetics, philosophy, and science. His abstractions, created over the span of more than forty years, explore visually infinite interpretations of form and color based on his intellectual theories. A writer and teacher, Lisa advanced a utopian vision of mid-century Latin American abstraction. Intended for his students and never exhibited during his lifetime, Lisa’s private archive of paintings has now posthumously been displayed around the world to great acclaim, and his role is now being fully recognized.”

Lisa created his paintings for his students; their reduced size invites close exploration in intimate spaces. For this reason, the 1927–28 installation in small rooms designed by Soviet artist El Lissitzky for his constructivist paintings (his Abstrakte Kabinett), inspired the McMullen display and exhibition title.

Organized by the Fundación Juan March, The Abstract Cabinet opened at the Museu Fundación Juan March in Palma and traveled to the Museo de Arte Abstracto Español in Cuenca with loans from the Fundación Esteban Lisa and the Fundación Juan March. The McMullen installation, curated by Elizabeth Thompson Goizueta, adds works from Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the McMullen Museum, and a private collection.

The Abstract Cabinet is accompanied by a catalogue edited by Manuel Fontán del Junco and María Toldo and published by the Fundación Juan March for the McMullen Museum. With contributions by scholars Edward J. Sullivan, Rafael Argullol, and Julio Sánchez Gil, it also features the first English translation of Lisa’s seminal text, Kant, Einstein, and Picasso. The English version of The Abstract Cabinet catalogue was supported by a grant from the Colgate-Palmolive Company in memory of Bartlett Harding Hayes Jr.

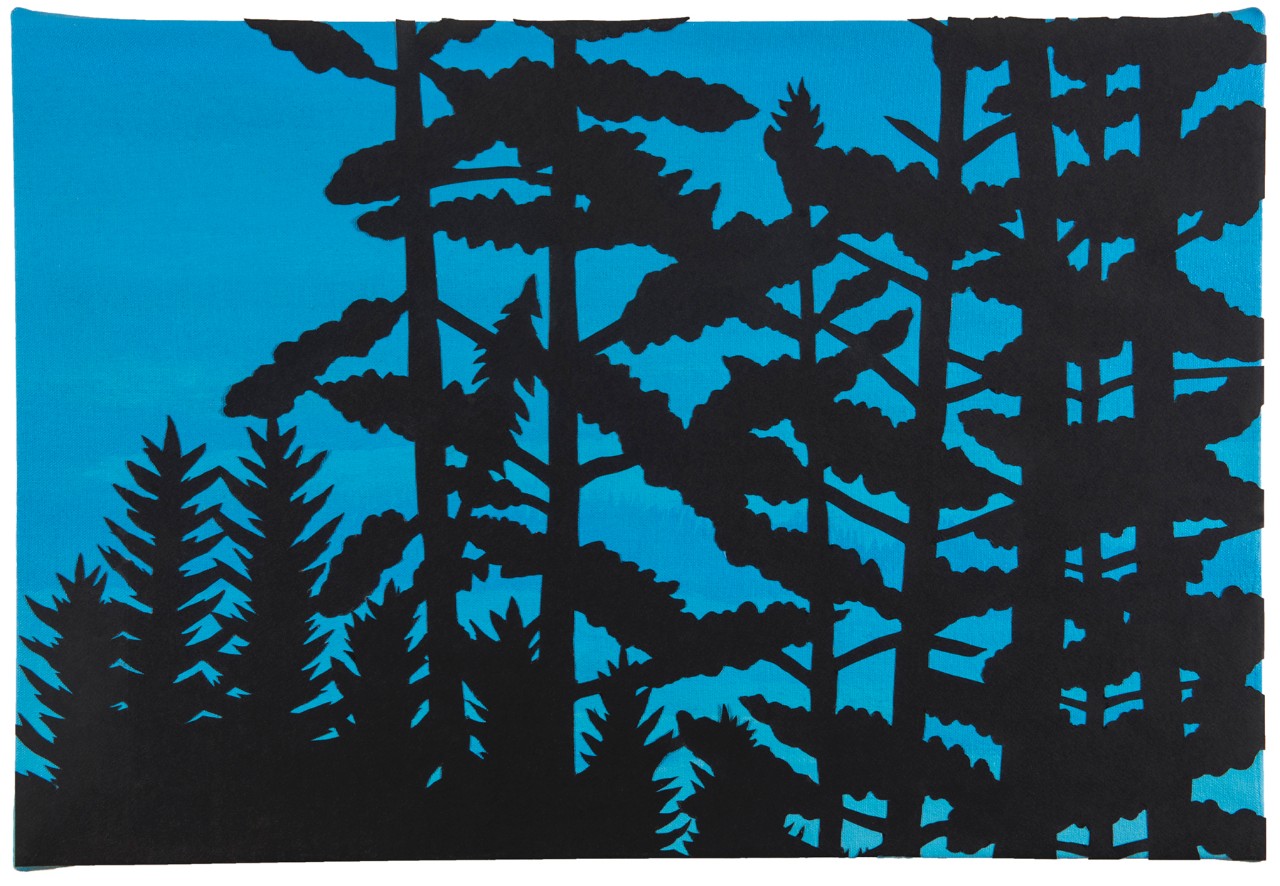

New England Sky: Alston Conley

Atrium, September 10–December 10, 2017

New England Sky showcases the tree and sky collages of BC Professor of the Practice of Art Alston Conley. The artist’s skyscapes build on the landscape tradition established centuries ago in Belgium and the Netherlands, attesting to an enduring desire by artists to “mirror nature” wherever it may be.

“I live under a New England sky,” Conley explains. “The light, its color, intensity, sensation, season, and length of day influence my psyche, mood, interior life, and art practice. The long hours of daylight during summer and short hours during winter define our seasons, influence our lives, and distance us from our southern neighbors. The low sun, color-rich light, and long shadows of early morning or end of the day often silhouette the horizon or individual trees in shadow, while the light fills the sky.”

Conley uses both paint and collage to create his skyscapes. For his collages, he cuts paper forms with a razor knife, creating almost sculptural shapes that he silhouettes against a painted sky. Like French artist Henri Matisse, he carves into color; flattened trees overlap his radiant backgrounds, primarily landscapes of Maine and Massachusetts where he resides.

Conley has received numerous awards and grants, including from the National Endowment for the Arts, and his works are held in several museums as well as in corporate and private collections. A free e-catalogue with reproductions of all the paintings on display and an essay by Katherine Nahum [a retired BC faculty member] accompanies New England Sky.

—Rosanne Pellegrini | University Communications